In Wilkes County, North Carolina, Child Care Is ‘a Community Problem’

Leaders are working on community solutions to the ongoing crisis.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

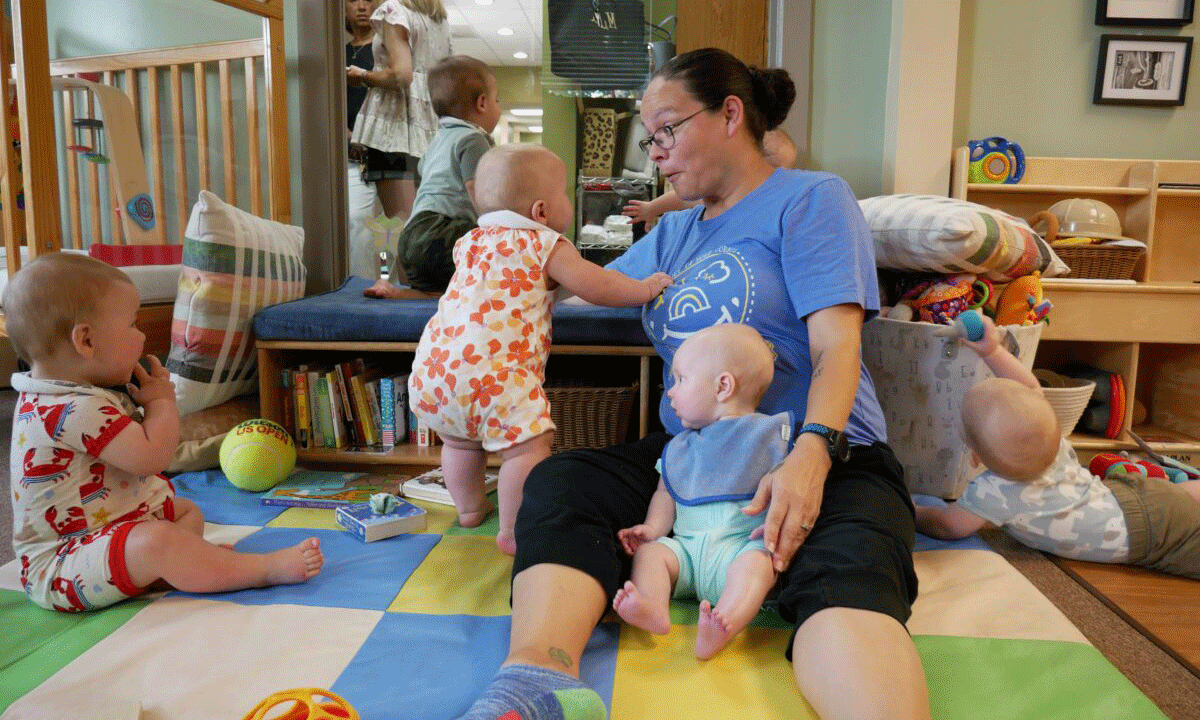

Seven babies play, coo, crawl, and attempt to walk on the floor of PlayWorks Early Care and Learning Center in North Wilkesboro.

They have no idea just how lucky they are to do so on this specific floor.

Three teachers hold the infants as they need comfort or food, redirect their walking attempts, and transfer one baby at a time to the changing station in the corner.

This is the only five-star infant classroom in Wilkes County. It serves eight babies, seven of whom were present during this visit.

“There’s a huge, huge need for infant care,” said Katy Hinson, who runs PlayWorks with her mother, Sharon Phillips. “The majority of our calls are for infant and toddler ages,” she said.

Child care options have dwindled in Wilkes County and in communities across North Carolina in recent years. From 2007 to 2022, the number of programs in Wilkes has dropped from 83 to 29, according to a new study released this summer funded by the Leonard G. Herring Family Foundation.

As the federal funds that have helped stabilize programs during the pandemic run out at the end of the year, affordable high-quality child care is about to become even harder to find in North Wilkesboro and across the state.

Along with increased tuition rates and potential wage cuts for teachers, the end of stabilization grants will mean one less teacher in the room of the eight babies at PlayWorks.

“We won’t be able to pay three people in each room, which is going to lessen the quality, which we don’t want to do,” Hinson said.

Across the state, a report from The Century Foundation predicts 155,539 children will lose child care access as the federal funds expire. That represents 1,778 closed programs, 5,983 lost child care jobs, $416 million in lost earnings for parents, and $19 million less in state income taxes.

Advocates and certain policymakers this legislative session have pushed for a one-time $300 million investment to help programs avoid that funding cliff for another two years. Those funds were not proposed in either the House or Senate budget proposals.

Diagnosing the need

As state budget negotiations continue in Raleigh, Wilkes County leaders are getting to work. The Wilkes Child Care Task Force, assembled about a year ago, held an event earlier this month to announce the release of a child care study, raise awareness about the problem posed for families and businesses, and discuss what can be done to help.

“When we had our very first focus group, there was a gentleman that stood up and said, ‘I don’t have children in child care. Why does this matter to me?’ And that was the voice of the community,” said Michelle Shepherd, executive director of the Wilkes Community Partnership for Children. “And now, look, a year later, this is a community problem — because of businesses, and bringing in industry, and the aging out of our current residents while we’re going to have an increase of children — it’s a community problem.”

The child care study, which was released by the Wilkes Economic Development Corporation (EDC), found that the county needs 836 more child care seats for children younger than five years old, almost double its current capacity of 909 seats.

The study estimated that based on the number of parents who are not currently working and the percentage of those who desire to be, offering adequate child care access in the county would add 1,000 individuals to the labor force. Wilkes EDC is communicating that figure to local businesses. The county’s labor force participation has declined from 61% in 2007 to 52% in 2021.

“It’s definitely an employer problem,” said LeeAnn Nixon, president of Wilkes EDC.

That’s why one of the study’s main recommendations is to engage the business community, both as a source of funding and as a source of training and support for new and existing providers.

“We wanted to understand the business model of the child care provider,” Nixon said. “The more we can understand that, the more we find ways to help them with resources and training.”

‘They deserve so much more’

Perhaps the most important thing to know about a child care provider’s business model is that 60% to 80% of its expenses go to teachers’ wages. It is a labor-intensive industry with high turnover, especially since the pandemic. And the smaller the teacher-to-child ratios, the better the quality, and the more expensive the labor.

Rachel Brionez, one of the three teachers in the PlayWorks infant classroom, has been in that very classroom for 10 years, since the center opened. At a previous center, Brionez said she took care of five infants by herself. She has been delighted with the work environment at PlayWorks, she said.

Brionez has an associate degree in early childhood education and cares deeply about her work.

“There’s a lot more that goes into it than just sitting and being with them,” Brionez said. She and her colleagues write lesson plans, aligned to state standards, just as K-12 teachers do. They keep documentation of each child’s progress. They maintain individualized plans for how to move each child toward milestones. They understand what is developmentally appropriate and when a child needs extra supports.

“We’re not babysitters,” said Jennifer Lumley, another teacher in the room.

The center has used the expiring federal relief funds for $3 per hour raises across the board, Hinson said. For a teacher with just an early childhood credential, that meant a raise of $10 to $12 or $13 an hour, depending on the person’s experience. For a teacher with an associate degree, that has meant a raise of $12 to $14 or $15 an hour.

“Which is still too little,” Hinson said. “They deserve so much more.”

Across North Carolina, wages for lead teachers have increased by 21% after the federal grants, from a median hourly wage of $11.50 to $13.92, according to survey results released in April from the North Carolina Child Care Resource & Referral Council.

Hinson said she is aware of the post-pandemic staffing challenges of other providers, but that her staff has been relatively stable.

“We try to take care of our teachers,” she said. “We treat them like humans — and professionals.”

When EdNC asked if the program will be able to sustain those wage increases, Hinson said she was still unsure.

That’s because sustained wages will mean increased fees for parents. This is the catch-22 of the child care business for directors like Hinson and Phillips who want to take care of both teachers and families.

They charge $895 per month for infant care, which is below the market rate for five-star care, because they know many parents can not afford more. They know that taking care of one group — by increasing wages for teachers — inevitably means adding stress to the other — by increasing tuition fees for families.

Ten minutes away at Wilkes Developmental Day School, Patsy Reavis, executive director of the center, is stuck grappling with the same financial equation as Hinson and Phillips.

The majority of children at the center have special needs, making them eligible for a specific allotment of funding from the Department of Public Instruction (DPI). Reavis estimates that the true cost of care for a child with special needs is about $1600 per month. The DPI funds cover $996 per child. For the typically developing child, she estimates high-quality care costs $1200 per month. Finding the funds for those costs means blending multiple funding streams: private tuition, child care subsidy, NC Pre-K, local contributions, and small grants here and there.

“There’s a shortage everywhere,” she said. “So we’ve got to get very, very creative.”

Reavis has also used federal stabilization funds to increase teacher wages. She raised hourly pay for a teacher with an associate degree from $12 to $15.50 — with similar boosts across the board, plus three rounds of bonuses.

“I refuse to take money away from the staff,” she said. “It’ll be interesting … There’s been so much attention on early education, now I’m hoping that it will generate the money.”

In the meantime, Reavis is worried about tackling hunger in her community and addressing the increased mental health needs of children and families, as well as of teachers.

She has a rule called “code break” to support teachers in particularly stressful moments, or moments where they are “confronting a situation that is causing their blood pressure to go up way too much,” she said.

During a code break, three or four adults will show up at the classroom immediately and give the teacher space to take a breath.

“I do things like that for (teacher) retention,” Reavis said. When considering how to best support her staff, she said, “I try to find everything I can.”

Despite the chaos of running a child care business, Reavis is hopeful about the direction of the county and the state.

“This is this the most transitional time I have ever experienced,” she said. “I think the good thing is we’re making businesses and politicians aware that it if we’re not here, no one else is going to be at work either,” she said. “So I’m thinking that information will trigger the funding that’s needed.”

This fight is not new to her. Reavis has been in the field since 1990, and she’s been advocating for change the entire time.

“I used to encourage every child care provider in this county to close down one day without notice, and then go to Tyson and say, ‘Did you have a lot of absences yesterday?'” she said with a chuckle. “I couldn’t talk them into doing that.”

What can be done?

The Wilkes EDC study is recommending attacking the problem from all angles: retaining teachers in the field and building an incoming pipeline, helping existing programs with their business models and making it easier for new providers to open, helping families navigate the current child care system and expanding parents’ options.

“I think we need to, quite frankly, not put all our eggs in one basket,” said Johanna Anderson, a consultant with the Leonard G. Herring Family Foundation who has worked with the task force throughout the study. “We have to chip away and make some movement in a variety of ways and be open to a variety of solutions.”

Anderson said the foundation will decide on further investments as the task force and its subcommittees get to work on the study’s recommendations (see full list of recommendations here).

But she also said the systemic nature of these problems will require partnerships with other communities doing similar work, as well as advocacy for statewide, sustainable, and long-term funding.

“Child care is not a privately funded solution solely,” Anderson said. “We can spark ideas, we can do some research, we can do some seed funding. But to really move the needle on child care, it’s going to have to include public resources, both existing and new.”

This article first appeared on EducationNC and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)