In Vermont’s Ed Secretary Search, A New Issue Rises to The Surface: Reading

Advocates are pushing for a new secretary of education to prioritize literacy instruction amid a nationwide reckoning over how kids learn to read.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As Vermont looks to hire a new secretary of education, Vermonters have weighed in with their preferred qualifications for a candidate. The state’s top education official, parents, educators and administrators say, should support public education, promote equity and opportunity for students, and revitalize what some see as an ineffectual agency.

Some Vermont advocates are pushing for a secretary with expertise in one particular area: teaching kids to read.

“We feel like there’s a tremendous opportunity for our state right now in appointing a leader who has the reading crisis high on their radar,” said Laurie Quinn, the president of the education nonprofit Stern Center for Language and Learning. “Who understands the opportunity that we have right now in Vermont to turn the reading crisis around for our kids.”

The push comes amid a nationwide reckoning over how kids learn to read, as a grassroots advocacy movement pushes schools to change their reading curricula to better follow scientific data.

Legislatures in dozens of states have implemented reforms intended to bring reading instruction in line with that research. Now, Vermont advocates are seeking a new secretary who will follow in their footsteps.

‘Someone that understands that science’

A growing number of educators, parents, teachers and lawmakers across the country are arguing that schools have been teaching kids to read the wrong way.

Galvanized in part by an American Public Media podcast called Sold a Story, advocates point to numerous studies that show that children learn reading better when they are explicitly instructed to connect letters and sounds, also known as phonics.

But for years, they argue, school reading curricula have omitted or underemphasized phonics instruction — to the detriment of students.

“With the secretary of ed vacancy, we really need someone that understands that science, and why it’s so important to support teachers — so that we can therefore support our kids,” said Abigail Roy, a board member at the International Dyslexia Association’s Northern New England Alliance and an evaluator at the Stern Center.

Through the Dyslexia Association, Roy has led a campaign urging Vermonters to write letters to the Vermont State Board of Education and governor asking them to choose a secretary who knows how to teach reading.

“Now is the time to organize efforts to encourage Governor Scott and members of the State Board of Education to choose a Secretary that is knowledgeable in the Science of Reading and supportive of structured literacy instruction in our Vermont classrooms,” the association said on its website.

More than a dozen Vermonters have drafted letters or submitted testimony to the State Board of Education asking for a secretary who will prioritize literacy instruction. A Seven Days cover story last week also raised the issue’s profile.

How bad is it?

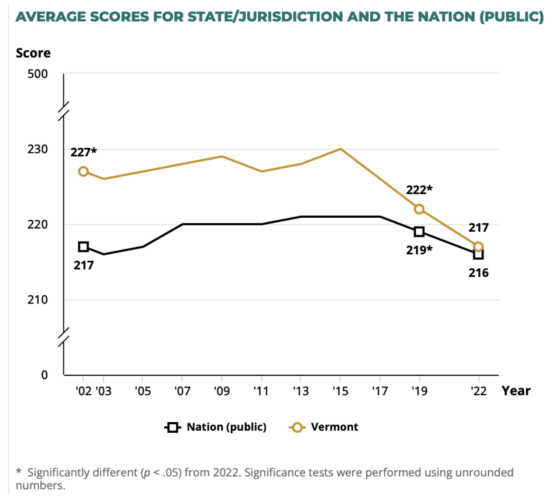

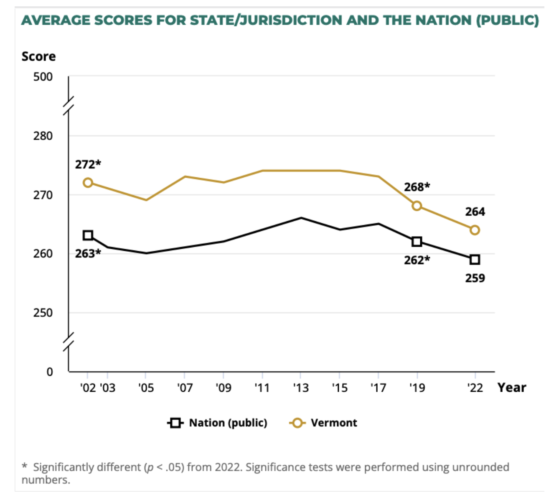

Every other year, Vermont fourth and eighth grade students are tested in reading and math by the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP, a standardized test sometimes called the Nation’s Report Card.

For much of the 2000s, Vermont’s average test scores in reading and math were largely steady, even ticking up slightly. According to NAEP, the state’s average scores in reading were at a modest 13-year high in 2015. Around that same year, the state recorded highs in the percentage of students — 45% — who scored “proficient” and above at the tests.

That year, however, marked a turning point. After 2015, Vermont’s NAEP reading scores started to drop, a decline that continued through the Covid-19 pandemic.

By 2022, 71% of the eighth graders tested in Vermont were scoring below a “proficient” level — up from 60% in 2002. Among fourth graders, 68% of those tested were below proficient, compared to 61% 20 years earlier.

Those declines largely mirror national trends. The state’s average test scores in mathematics have followed a similar trajectory, peaking around 2013 and declining in the years since. (The state of Vermont also administers its own standardized tests, but they offer a much more limited range of data.)

Is inadequate reading instruction behind the state’s middling scores? Some advocates speculated that it was. Quinn, of the Stern Center, said that she had consulted with a colleague who guessed that poor reading curricula became “entrenched in the decade prior.”

Others said it was best not to dwell on that data.

“If you spend time with youth, and watch them and see them attempt to construct sentences, there’s plenty of qualitative data in every classroom,” said Dorinne Dorfman, a former administrator, teacher and board member at the regional International Dyslexia Association’s chapter. “It’s really evident in their everyday lives.”

Ted Fisher, a spokesperson for the Vermont Agency of Education, declined to make any state officials available for an interview. Asked about the causes behind that decline, Fisher referred VTDigger to a 2019 press release from the Vermont Agency of Education.

“I urge school districts to pay attention to these results and make sure we are focused on providing high-quality instruction in core skills like literacy and mathematics,” then-Secretary of Education Dan French said in the release.

‘Take it into consideration’

Not everyone is convinced that the silver bullet is more phonics instruction.

Marjorie Lipson, a founding board member of the literacy nonprofit Partnerships for Literacy and Learning and former education professor at the University of Vermont, said that the focus on phonics oversimplifies the many factors that go into how kids learn to read.

“My argument is not with phonics,” Lipson said, noting that it’s a key part of curricula. “It’s with an approach that says that’s all that’s important, and that you need to hold back other aspects of becoming a reader until after that job is done.”

She likened phonics instruction to practicing shooting a basketball: “You could have a child go into a gym and practice shooting hoops till they, you know, collapsed from fatigue,” she said. “At the end of the day, if that’s all they’d ever done — was shoot hoops — they would be pretty skilled at shooting hoops. But they wouldn’t be a good basketball player.”

Jay Nichols, the executive director of the Vermont Principals Association, compared the current discourse to the “reading wars” of the 1980s, when educators debated how much of a role phonics instruction should play in classrooms.

“It’s exactly the same,” he said. “The pendulum’s kind of swung back and forth. And I think it’s, as usual, the answer’s somewhere in the middle.”

Either way, it’s not clear that advocates will succeed in getting a secretary who will prioritize reading instruction.

Under Vermont law, the State Board of Education is supposed to present at least three candidates for the position to the governor, who will make a final choice. The job application window closed on Oct. 5.

Jennifer Samuelson, the chair of the state board, declined an interview, saying she was preparing for a trip. Asked about the campaign for a secretary of education to prioritize literacy, she said in an email that “I think this is an area that is clearly of interest to a lot of Vermonters.”

But the board had not discussed the topic, she said. She declined to say whether the body would prioritize reading instruction in its search for a new secretary, saying that information about the hiring process was “privileged” under Vermont law.

Nor is it clear how much Gov. Phil Scott will focus on the issue.

In response to an emailed inquiry from VTDigger, Jason Maulucci, a spokesperson for Scott, said, “The Governor will certainly will take it into consideration, along with other public feedback.”

This story was originally published in VT Digger.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)