In-Depth: Michael Petrilli’s 5-Part Argument About School Choice, Tests & Long-Term Outcomes

This series of essays originally appeared at EdExcellence.net

Part I: How to think about short-term test score changes and long-term student outcomes:

Last month, the American Enterprise Institute published a paper by Colin Hitt, Michael Q. McShane, and Patrick J. Wolf that reviewed every rigorous school-choice study with data on both student achievement and student attainment — high school graduation, college enrollment, and/or college graduation. They contend that the evidence points to a mismatch, specifically that “a school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes.”

Below is a series of essays I wrote on the paper, which I believe is fundamentally flawed. I have several concerns, including:

1. The authors included programs in the review that are only tangentially related to school choice and that drove the alleged mismatch, namely early-college high schools, selective-admission exam schools, and career and technical education initiatives.

2. Their coding system — which they admit is “rigid” — sets an unfairly high standard because it requires both the direction and statistical significance of the short- and long-term findings to line up.

3. In their conclusions, they extrapolated from their findings on school choice programs and inappropriately applied them to schools.

First, let’s consider the value of looking at long-term outcomes and what they can and cannot tell us about schools and programs.

Let’s start with where the AEI authors got it right. We all hope that our preferred education reforms, at least the most ambitious ones, will “change the trajectories of children’s lives.” That’s particularly true for children growing up in poverty, who typically face depressing odds of success if they attend mediocre schools. They may drop out before finishing high school, or they might graduate but with minimal skills. Either way, they’re unlikely to complete postsecondary education or training or master the “success sequence,” and are thus likely to work low-wage jobs and not enjoy the fruits of upward mobility. Many will struggle to form an intact family, and their children will grow up poor and then repeat the cycle. It’s a bleak picture.

It’s different for affluent children, of course. Great schools may change their trajectories, too, but it will be subtler because they will probably do reasonably well regardless due to the advantages they usually receive at home. Most will graduate high school and go to college no matter what. But with a great education, they have a good chance of learning more, which will help them get into and through a better college and eventually do more and better in the labor market.

For all children, we hope that fantastic schools will benefit them in other long-term ways that are important but harder to measure: encouraging them to become active, informed citizens; identifying strengths and interests that they might put to good use in a career; and helping them become people of good character.

So, yes, long-term outcomes are extremely important, especially for children for whom positive outcomes are far from assured.

Will all effective programs show long-term effects?

As the AEI authors write, it would be deeply disappointing if major reforms of schools and schooling moved the needle on test scores but didn’t have a lasting impact on kids’ lives. In effect, we’d be fooling ourselves into thinking that we’re making a big and enduring difference when in reality we might be wasting our time or money that could better be spent on other strategies.

Of course, it would be unfair to apply such a high standard to small, incremental changes, like adopting a better textbook or extending the school day. Nobody would expect tiny tweaks to have profound impacts, such as transforming a future high school dropout into a college graduate. But if they help lots of students become marginally more literate or numerate, they are still worth doing.

For major, expensive, disruptive reforms, however, stronger long-term outcomes are not too much to ask. And of course the most effective reformers are already aware of this. Consider KIPP, which has been obsessed from day one not just about student achievement but also at getting its KIPPsters to and through college, consistently tracking its numbers and refining its model. Which has properly led the organization to look at much more than just short-term test scores as indicators of whether their students are on track. Much of today’s interest in non-cognitive skills grew out of this work.

If a program showed large and significant impacts on achievement, especially for low-income kids, but poor results on long-term outcomes, it would certainly raise alarms. It might indicate that the program was overly focused on reading and math, or was teaching to the test, or was crowding out other strategies or activities that would actually help kids succeed in the long run. Unless, of course, there were issues associated with the long-term measures themselves.

The problem with high school graduation rates

It almost goes without saying, but at a time when high school graduation rates are skyrocketing, in part thanks to “credit recovery” initiatives and other dubious practices, we must view this measure with a healthy dose of skepticism. Now that most states allow students to graduate without passing an exit exam, or even a set of end-of-course exams, we cannot pretend that the standards for graduation are consistent from school to school. As a result, we must be careful with how we interpret positive or negative impacts on high school graduation rates, especially when evaluating high schools themselves. Boosting graduation rates might mean that schools are better preparing students to succeed — or it could mean that they have lowered their standards.

It would also be inappropriate to assume that a high school that boosts student achievement and better prepares its graduates to succeed in college would also raise its own graduation rates. In fact, we know from a 2003 study by Julian Betts and Jeff Grogger that there is a trade-off between higher standards (for what it takes to get a good grade) and graduation rates, at least for children of color. Higher standards boost the achievement of the kids who rise to the challenge, and helps those students longer-term, but it also encourages some of the other students to drop out. If a high school could manage to both boost achievement and keep its graduation rate steady, that would be an enormous accomplishment. Yet by the logic of the AEI review, such a school would show a mismatch between short-term achievement impacts and “long term” attainment ones. Such logic is faulty.

Programs that don’t test well

On the other end of the scale are programs that appear to be failures when judged by short-term test-score gains, but that produce impressive long-term results for their participants. It’s this category that most concerns Hitt, McShane, and Wolf, especially in the context of school choice. “In 2010,” they write, “a federally funded evaluation of a school voucher program in Washington, DC, found that the program produced large increases in high school graduation rates after years of producing no large or consistent impacts on reading and math scores.” Later they conclude that “focusing on test scores may lead authorities to favor the wrong school choice programs.”

It’s a legitimate concern, and one I share (setting aside my misgivings about high school graduation rates expressed above). I played a tiny role in helping launch the D.C. voucher program when I served at the U.S. Department of Education, and I support the expansion of private school choice programs for low-income students. I can imagine why the private schools in the D.C. program might struggle to improve test scores, especially when compared to highly effective (and highly accountable) D.C. charter schools and an improving public school system. But I can also imagine that the experience of attending a private school in the nation’s capital could bring benefits that might not show up until years later: exposure to a new peer group that holds higher expectations in terms of college-going and the like; access to a network of families that opens up opportunities; a religious education that provides meaning, perhaps a stronger grounding in both purpose and character, and that leads to personal growth.

It would be a shame — no, a tragedy — for Congress to kill this program, especially if it ends up showing positive impacts on college-going, graduation, and earnings. The same might be said about large voucher programs in Ohio, Indiana, and Louisiana, all of which have shown disappointing early findings in terms of student achievement but might be setting children on paths to future success. Policymakers should be exceedingly careful not to end such programs prematurely.

***

There are therefore several things to think about as we further explore the AEI study: long-term outcomes do indeed matter a lot, especially for poor kids; if large test-score gains don’t eventually translate into improved long-term outcomes, it is a legitimate cause for concern; and we must stay open to the possibility that some programs could help kids immensely over the long haul, even if they don’t immediately improve student achievement. At the same time, we should be skeptical about using high school graduation rates as valid and consistent measures of attainment.

So is there really a mismatch between short-term scores and long-term outcomes, especially for school choice programs? And do existing studies really raise red flags about using test scores to make decisions about individual schools?

Part II: When looking only at school choice programs, both short-term test scores and long-term outcomes are overwhelmingly positive

The AEI paper focuses on a specific question: Is there is a disconnect for school choice programs when it comes to their impact on student test scores versus their impact on student attainment outcomes, namely high school graduation, college entrance, and college graduation rates?

It claims to find such a disconnect. As the authors put it, “A school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes.” But read the fine print because this conclusion follows from two big decisions the authors made, both of which are highly debatable. Had they gone the other way, the results would show an overwhelmingly positive relationship between short-term test score changes and long-term outcomes.

What were those decisions?

1. The authors included programs in the review that are only tangentially related to school choice and that drove the alleged mismatch, namely early-college high schools, selective-admission exam schools, and career and technical education initiatives.

2. Their coding system — which they admit is “rigid” — sets an unfairly high standard because it requires both the direction and statistical significance of the short- and long-term findings to line up.

I am also concerned that the authors extrapolated from their findings about programs and inappropriately applied them to schools.

In this post, I tackle the first concern: whether Hitt, McShane, and Wolf included studies they should not have. How might their results look had they chosen differently?

What counts as a school choice program?

The AEI authors were extremely inclusive when deciding which studies to review. In their words:

We use as broad a definition as possible for school choice. We do so for two reasons. First, we wanted to gather the largest number of studies possible to examine the relationship between achievement and attainment impacts across studies. Second, school choice is bigger than voucher programs and charter schools. Many large districts have embraced a portfolio model of school choice governance, which intentionally offers a wide array of public (and sometimes private) school choices to parents. The diversity of the studies we collected mirrors the diversity of choice options that portfolio school districts attempt to offer.

That’s fair up to a point; surely looking beyond just vouchers and charter schools makes sense in a world with many kinds of choice. But I would add two commonsense criteria for deciding what should be in and what should be out. First, is school choice central to the program, or is it incidental? And second, is it a program for which a reasonable person would expect to see both achievement gains and positive long-term outcomes if the program is successful? Let’s apply these criteria to the types of programs the authors reviewed.

There’s no doubt that private school choice, open enrollment, charter schools, STEM schools, and small schools of choice count as “school choice” programs, ones that legitimately could be expected to boost both short-term test scores and long-term outcomes for their participants if effective.

But the other categories fail our test. Early-college high schools are nominally schools of choice. No one is forced to attend them, but choice is incidental to the model. The heart of the approach is getting students on college campuses, taking college courses, and pointing them toward a possible associate degree along with their high school diploma.

Likewise with selective enrollment high schools, such as Stuyvesant High School in New York City. Sure, students “choose” to go to Stuyvesant in the same way that they “choose” to go to Harvard. But if ever there was an example in which schools choose the students rather than the other way around, this is it. And given these schools’ highly unusual, super-high-achieving student populations, we wouldn’t be surprised if was hard to detect either achievement or attainment effects. Everyone who goes to these schools or almost gets in (the students used as controls in the relevant studies) are super high-achieving and likely to graduate from college, not to mention high school, regardless.

Or consider Career Academies and other forms of career and technical education. Students enroll voluntarily in these programs, but what’s much more important is their unique missions and designs. We wouldn’t necessarily expect CTE students to show as much academic progress as their peers in traditional high schools because they are spending less of their time on academics! But high-quality CTE could still boost high school graduation, postsecondary enrollment, and postsecondary completion.

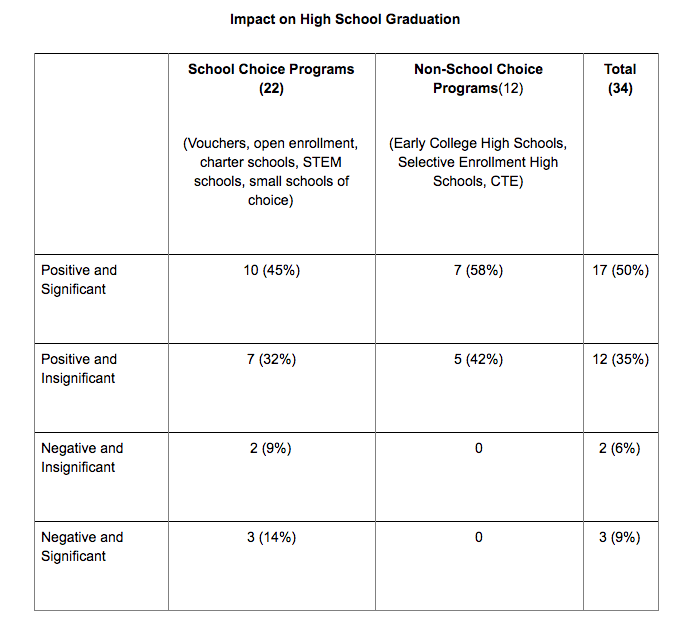

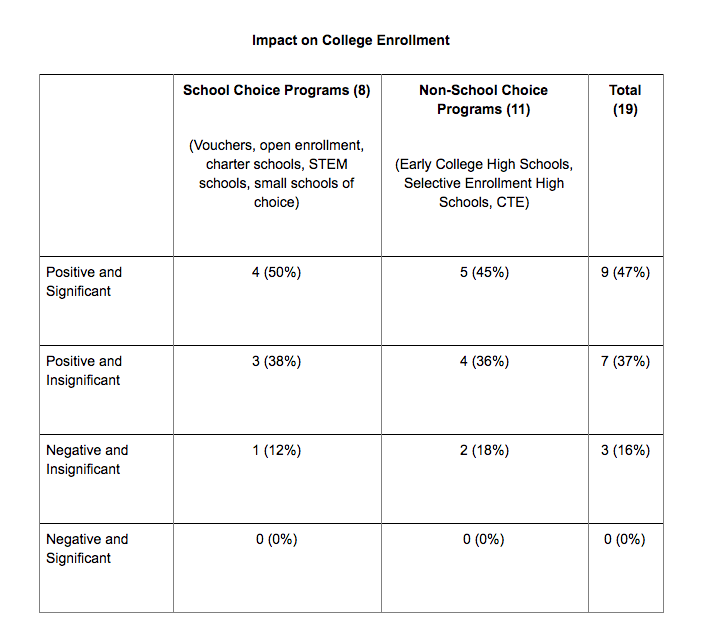

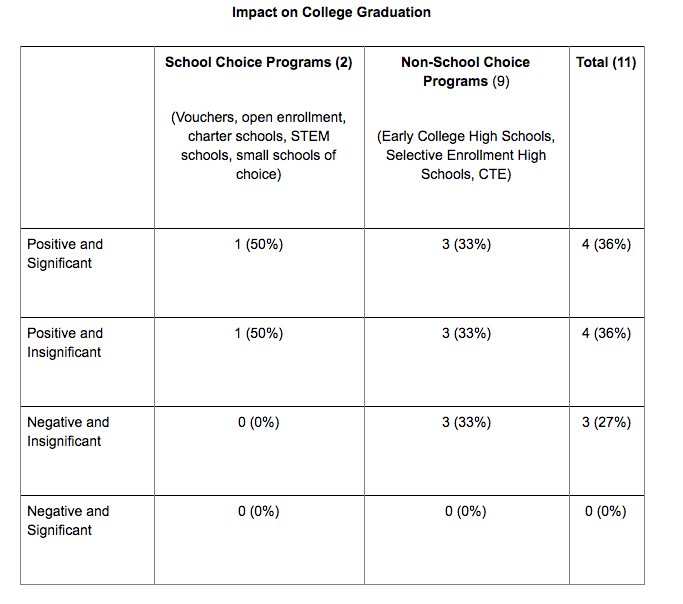

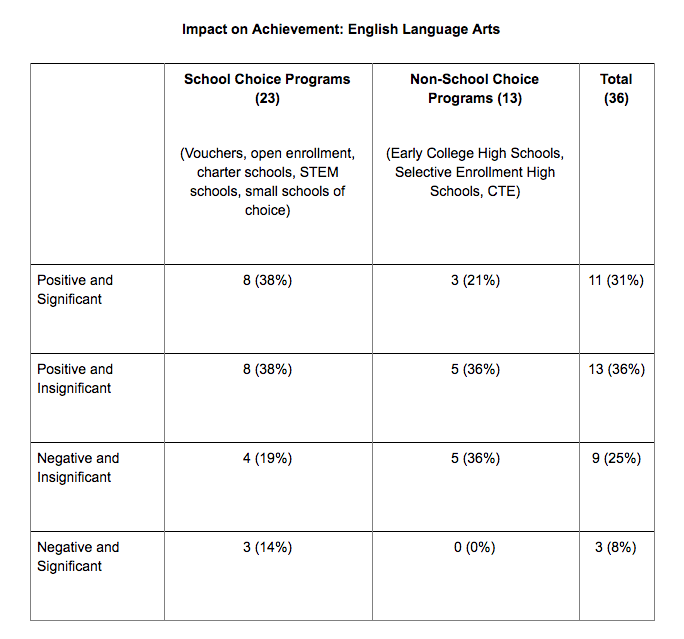

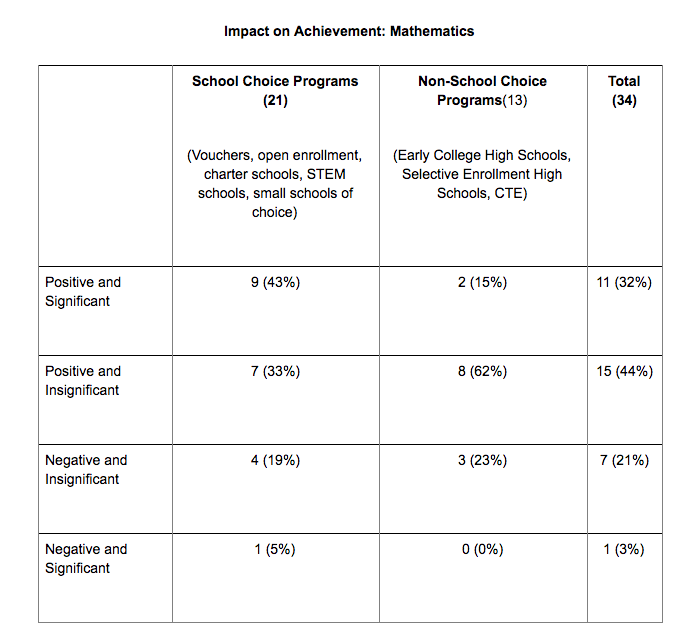

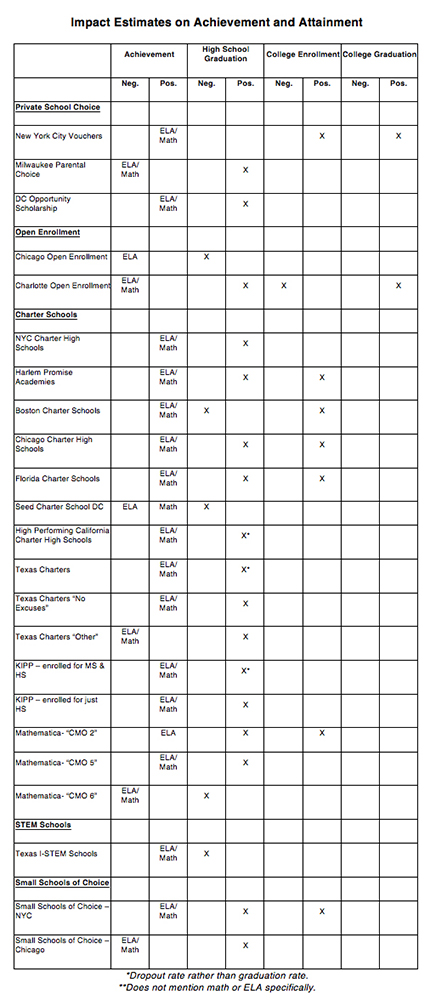

So let’s see how the results look for the bona fide school choice programs versus the others. (See here for a table listing all studies, how they were coded by the AEI authors, and which ones I counted as “school choice.”)

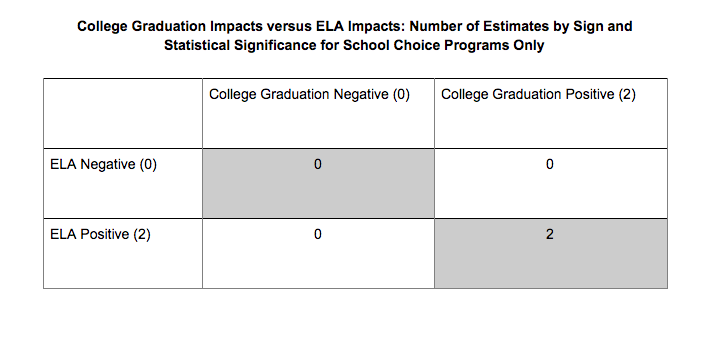

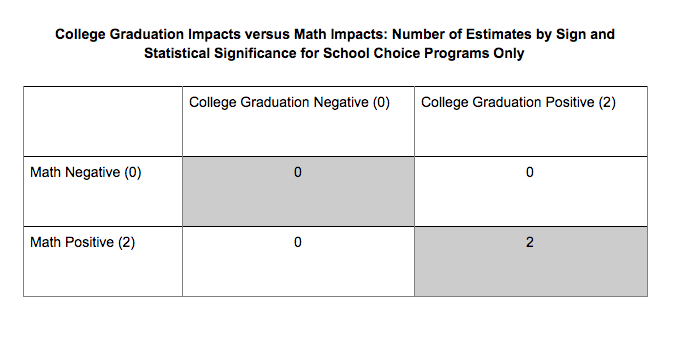

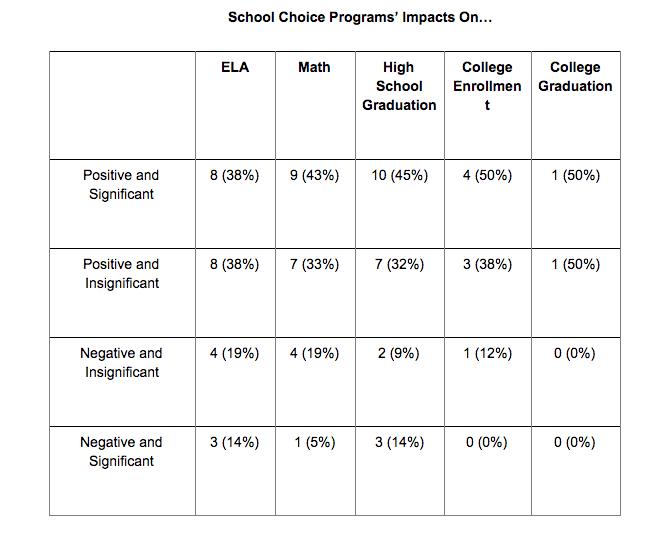

Several findings emerge from these tables. First, the school choice programs show overwhelmingly positive impacts on both achievement and attainment; it’s more of a mixed bag for the non–school choice programs, which tend to do worse on achievement but well on attainment. And that leads to the second key point: the mismatch between short-term test scores and long-term outcomes — to the extent that it happens — is driven largely by the non–school choice programs. For bona fide school choice, there’s a very good match: 38 percent of the studies show a statistically significantly positive impact in ELA, 43 percent in math, 45 percent for high school graduation, 50 percent for college enrollment, and 50 percent for college graduation. If we look at all positive findings regardless of whether they are statistically significant, the numbers for school choice programs are 76 percent (ELA), 76 percent (math), 77 percent (high school graduation), 88 percent (college enrollment), and 100 percent (college graduation). Everything points in the same direction, and the outcomes for achievement and high school graduation — the outcomes that most of the studies examine — are almost identical.

So is it true, as Hitt, McShane, and Wolf claim, that “a school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes”? It sure doesn’t appear so. But perhaps these aggregate numbers are hiding a lot of mismatch at the level of individual programs.

Part III: For the vast majority of school choice studies, short- and long-term impacts point in the same direction

Above, I argue that Hitt, McShane, and Wolf erred in including programs in their review of “school choice” studies that were only incidentally related to school choice or that have idiosyncratic designs that would lead one to expect a mismatch between test score gains and long-term impacts (early college high schools, selective enrollment high schools, and career and technical education initiatives). If you take those studies out of the sample, the findings for true school choice programs are overwhelmingly positive for both short- and long-term outcomes.

Below I’ll take up another problem with their study: They set an unreasonably high bar for a study to show a match between test score changes and attainment. Let me quote the authors themselves, in a forthcoming academic version of their AEI article:

Our coding scheme may seem rigid. One can criticize the exactitude that we are imposing on the data, as achievement and attainment results must match regarding both direction and statistical significance. We believe this exactitude is justified by the fact that the conclusions that many policymakers and commentators draw about whether school choice “works” depends on the direction and significance of the effect parameter. As social scientists, we would prefer that practitioners rigidly adhere to the convention of treating all non-significant findings as null or essentially 0, regardless of whether they are positive or negative in their direction, but we also eschew utopianism. Outside of the ivory tower, people treat a negative school choice effect as a bad result and a positive effect as a good result, regardless of whether it reaches scientific standards of statistical significance. Since one of our goals is to evaluate the prudence of those judgments, we adopt the same posture for our main analysis.

And later:

Our resulting four-category classifications might be biasing our findings against the true power of test score results to predict attainment results, as it is mathematically more difficult perfectly to match one of four outcome categories than it is to match one of three. Moreover, the disconnect between test score impacts and attainment impacts might be driven by a bunch of noisy non-significant findings not aligning which each other, which is exactly what we might expect noisy non-significant findings to do.

It is indeed a rigid approach the authors used in the AEI paper, and in the forthcoming academic version they appropriately test to see whether their findings might change if they treat non-statistically-significant findings as null, regardless of whether those findings point in a positive or negative direction. Their results were largely the same.

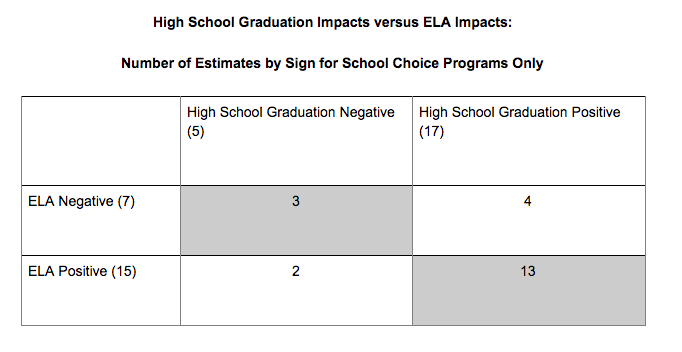

But there’s another reasonable way to look for matches, and that’s seeing whether a given study’s findings point in the same direction for both achievement and attainment, regardless of statistical significance. In other words, treat findings as positive regardless of whether they are statistically significant, and treat findings as negative regardless of whether they are statistically significant.

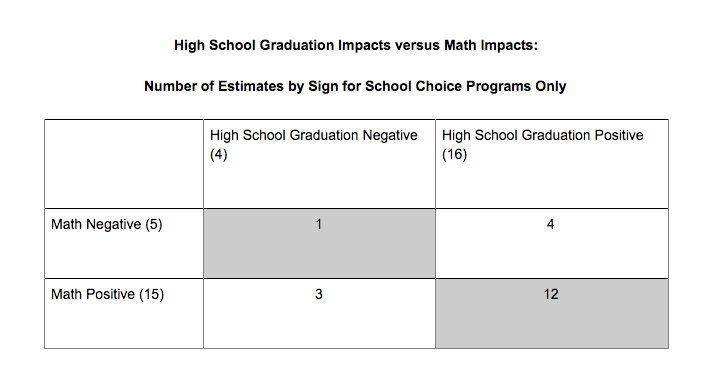

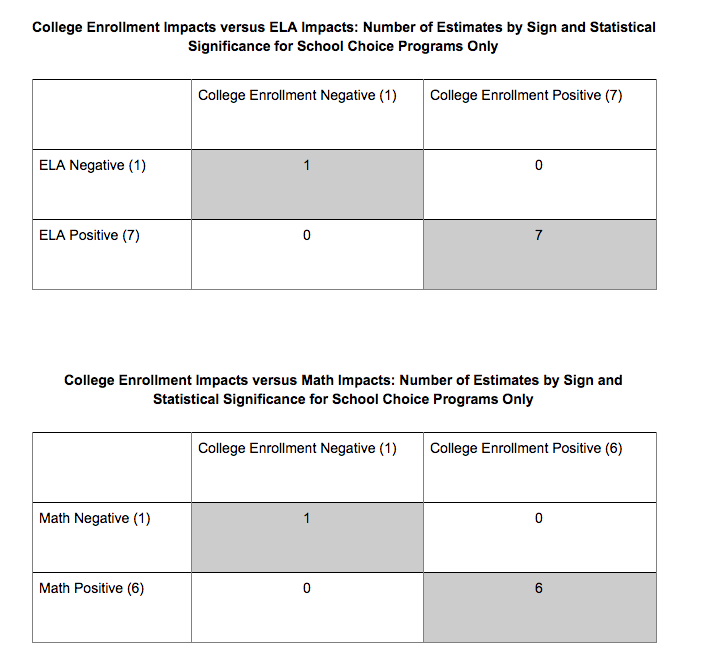

That’s what I do in the tables below, based on Hitt’s, McShane’s, and Wolf’s coding of the 22 studies of bona fide school choice programs. The shaded cells show the number of studies with findings that match — either both pointing in a negative or both pointing in a positive direction.

Analyzed this way, we see that the impacts on ELA achievement and high school graduation point in the same direction in 16 out of 22 studies, or 73 percent of the time. For math, it’s 13 out of 20 studies, or 65 percent. For college enrollment, the results point in the same direction 100 percent of the time.

Now, perhaps we should be worried about the six estimates in ELA and seven in math where achievement and high school graduation outcomes pointed in opposite direction. So let’s dig into those.

First, studies found that three school choice programs improved ELA and/or math achievement but not high school graduation:

1. Boston charter schools

2. SEED charter school

3. Texas I-STEM School

Keep in mind that for both SEED and the Texas I-STEM School, the results for achievement and high school graduation were both insignificant. So these might actually be matches. Still, for Boston charter schools, there is a clear mismatch, with significantly positive results for ELA and math and significantly negative results for high school graduation. So is this cause for concern? Hardly. As I wrote on Monday,

We know from a 2003 study by Julian Betts and Jeff Grogger that there is a trade-off between higher standards (for what it takes to get a good grade) and graduation rates, at least for children of color. Higher standards boost the achievement of the kids who rise to the challenge, and help those students longer-term, but it also encourages some of the other students to drop out.

There’s good reason to believe, based on everything we know about Boston charter schools and their concentration of “no excuses” models, that they are holding their students to very high standards. This is raising achievement for the kids who stay but may be encouraging some of their peers to drop out. This trade-off is a legitimate subject for discussion — is it worth it? — but it’s not logical to conclude that the test score gains are meaningless. Especially since Boston charters do show a positive (though statistically insignificant) impact on college enrollment.

How about the four programs that “don’t test well” — initiatives that don’t improve achievement but do boost high school graduation rates? They are:

1. Milwaukee Parental Choice

2. Charlotte Open Enrollment

3. Non-No Excuses Texas Charter Schools

4. Chicago’s Small Schools of Choice

(Only the Texas charter schools had statistically significant impacts for both achievement (ELA and math) and high school graduation. Milwaukee’s voucher program had a significantly negative impact on ELA; the findings for math and high school graduation rates were statistically insignificant. In Charlotte and Chicago, all of the findings were statistically insignificant.)

The other day, I wrote:

It’s this category that most concerns Hitt, McShane, and Wolf, especially in the context of school choice. “In 2010,” they write, “a federally funded evaluation of a school voucher program in Washington, DC, found that the program produced large increases in high school graduation rates after years of producing no large or consistent impacts on reading and math scores.” Later they conclude that “focusing on test scores may lead authorities to favor the wrong school choice programs.”

It’s a legitimate concern, and one I share … the experience of attending a private school in the nation’s capital could bring benefits that might not show up until years later: exposure to a new peer group that holds higher expectations in terms of college-going and the like; access to a network of families that opens up opportunities; a religious education that provides meaning, perhaps a stronger grounding in both purpose and character, and that leads to personal growth.

It would be a shame — no, a tragedy — for Congress to kill this program, especially if it ends up showing positive impacts on college-going, graduation, and earnings.

So I agree that these mixed findings are a red flag and should give policymakers pause before moving to kill off such programs. I’m encouraged that there are only four such studies in the literature among the 22 examined here, just one of which had statistically significant findings for both achievement and high school graduation. But still, such initiatives may well be changing students’ lives, although we wouldn’t know that by looking at test scores alone.

Does that mean that we shouldn’t use test scores to hold individual schools accountable? Including closing weak charter schools or cutting off public funding to private schools of choice if they diminish achievement?

Part IV: Findings about school choice programs shouldn’t be applied to individual schools

Above, I’ve shown that the overwhelming majority of studies looking at bona fide school choice programs find positive effects on both short-term test scores and long-term student outcomes, especially college-going and college graduation. It is simply incorrect to claim, as the AEI authors did, that “a school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes.”

Still, there are a handful of examples of school choice programs that diminished achievement but improved high school graduation rates, including the Milwaukee voucher program and a set of Texas charter schools. I agree with Hitt, McShane, and Wolf that it would be a mistake for policymakers to prematurely kill off initiatives such as these, which may be helping students in ways not captured by reading and math scores.

But does that mean we shouldn’t close individual schools that persistently hurt student achievement? Including charter schools? The AEI authors seem to think so. Jumping from their findings on programs and extrapolating them to schools, they write: “If test score gains are neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition for producing long-term gains in crucial student outcomes, then current approaches to accountability for school choice programs are questionable at best.… Focusing on test score gains may lead regulators to favor schools whose benefits could easily fade over time and punish schools that are producing long-lasting gains.”

Let me explain what’s wrong with this logic.

1. Nobody measures high schools by their test scores alone

Hitt, McShane, and Wolf seem to think that “regulators” are closing charter schools, or turning off the public funding to private schools participating in voucher programs, based merely on low test scores. To my knowledge, that is never the case, especially for high schools, because every state accountability system and every charter school authorizer looks at high school graduation rates, too. And of course the Every Student Succeeds Act requires those graduation rates to be baked into high school ratings. So an individual high school would need both low test scores and graduation rates to be at risk of landing in a “regulator’s” bull’s-eye. One with strong graduation rates would be fine.

2. Holding elementary or middle schools accountable for long-term impacts is not practical

But what about elementary or middle schools that diminish student achievement, yet somehow increase their pupils’ odds of graduating from high school many years later? Should we worry about regulators “punishing” such schools? Shouldn’t schools in those programs get a reprieve?

This is where we have to be careful to distinguish between programs and schools. The AEI team reviewed studies about the former, not the latter. We know from those studies that a handful of programs as a whole worsened achievement but improved graduation rates (a set of Texas’s charter schools, for example). What we don’t know is whether there was a similar mismatch at the school level. We don’t whether there were any, say, charter middle schools in Texas that reduced achievement but increased their students’ odds at graduating from high school. We simply don’t know.

Hitt, McShane, and Wolf would err on the side of leniency for schools with poor achievement, holding out hope that they might be helping their students long-term in ways not captured by test scores. This, they note, is particularly salient because these are schools of choice, and thus determined by parents to be better options than the alternatives.

There’s a case to be made that regulators should never overrule the wishes of parents, but that case is not informed by the evidence the AEI authors reviewed. There is simply nothing in the data to suggest that individual schools that diminish achievement are improving attainment. Nothing. So let’s have the debate on moral or philosophical or policy-preference terms, rather than pretending that empirical evidence signals the proper outcome.

And in my view, we shouldn’t grant low-achieving elementary and middle schools a reprieve while we wait to see whether they improve long-term outcomes, because by the time we had proof, the school in question would be years older. It might be a completely different place. We couldn’t possibly close a school based on how it affected an earlier generation of students. We must either hold elementary and middle schools accountable for the outcomes of current students or not at all.

***

Hitt, McShane, and Wolf are right to worry about promising programs and schools getting shuttered before they have a chance to prove themselves over the long term. High-quality charter authorizers address this concern by doing a comprehensive review of schools before deciding whether to close them. If there are reasons to believe that test scores don’t capture all the value the school is providing, its leaders have ample opportunities to make their case to officials. As a charter authorizer myself, I can say that we are eager to be persuaded by such evidence. And as Andy Smarick has argued, voucher programs need something akin to authorizers, too, so that decisions about participating schools can be informed by nuance and human judgment, not just by test scores and other data points. (Maybe that’s what Indiana is currently stumbling into.)

But the charter schools that do get closed are not, in my view and experience, diamonds in the rough. They are campuses with depressingly low pupil achievement, poor student-level growth, and very little successful teaching and learning in their classrooms. They are places where authorizers can see with their own eyes that weak instruction, mediocre curricula, poorly prepared or demoralized teachers, and often well-meaning but ineffective leaders add up to poor educational experiences for their charges. Is there some remote chance that such schools are doing something positive for their students that might be found by a study 10 years hence? I guess it’s possible. But there’s nothing in the research literature to suggest that it is so, and a lot in the literature to indicate that the kids — especially if they are poor — dare not wait that long.

Part V: Yes, impacts on test scores matter

A final summary of the paper and what I believe is wrong with it:

What the AEI authors did

Hitt, McShane, and Wolf set out to review all of the rigorous studies of school choice programs that have impact estimates for both student achievement attainment — high school graduation, college enrollment, and/or college graduation. To my eye, they did an excellent and comprehensive job scanning the research literature to find any eligible studies, culling the ones lacking the sufficient methodological chops, and then coding each as to whether they found impacts that were statistically significantly positive, insignificantly positive, insignificantly negative, or significantly negative.

They then counted to see how many studies had findings for short-term test score changes that lined up with their findings for attainment. After running a variety of analyses, Hitt, McShane, and Wolf concluded that “A school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes.”

Where the AEI paper erred

But the authors made two big mistakes, as I argued Tuesday and Wednesday:

● They included programs in the review that are only tangentially related to school choice and that drove the alleged mismatch, namely early-college high schools, selective-admission exam schools, and career and technical education initiatives.

● Their coding system — which they admit is “rigid” — set an unfairly high standard because it requires both the direction and statistical significance of the short- and long-term findings to line up.

Both of these decisions are subject to debate. There’s an argument for making the choices the authors did, but also for them going the other way. What’s key is that different choices would have resulted in dramatically different findings.

For bona fide school choice programs, short-term test scores and long-term outcomes line up most of the time

If we focus only on the true school choice programs — private school choice, open enrollment, charter schools, STEM schools, and small schools of choice — and we look at the direction of the impacts (positive or negative) regardless of their statistical significance, we find a high degree of alignment between achievement and attainment outcomes. That’s because, for these programs, most of the findings are positive. (That is good news for school choice supporters!)

Thirty-eight percent of the studies show a statistically significantly positive impact in ELA, 43 percent in math, 45 percent for high school graduation, 50 percent for college enrollment, and 50 percent for college graduation. If we look at all positive findings regardless of whether they are statistically significant, the numbers for school choice programs are 76 percent (ELA), 76 percent (math), 77 percent (high school graduation), 88 percent (college enrollment), and 100 percent (college graduation). Everything points in the same direction, and the outcomes for achievement and high school graduation — the outcomes that most of the studies examine — are almost identical.

We also find significant alignment for individual programs. The impacts on ELA achievement and high school graduation point in the same direction in 17 out of 22 studies, or 77 percent of the time. For math, it’s 13 out of 20 studies, or 65 percent. For college enrollment, the results point in the same direction 100 percent of the time.

Here’s how that looks for the specific studies:

Studies found that three school choice programs improved ELA and/or math achievement but not high school graduation: Boston charter schools, the SEED charter school, and the Texas I-STEM School. But there’s an obvious explanation: These are known as high-expectations schools, and such schools tend to have a higher dropout rate than their peers. That hardly means that their test score results are meaningless.

At the same time, there were four programs that “don’t test well” — initiatives that don’t improve achievement but do boost high school graduation rates: Milwaukee Parental Choice, Charlotte Open Enrollment, Non-No Excuses Texas Charter Schools, and Chicago’s Small Schools of Choice. (Charlotte also boosted college graduation rates.) Of these, only the Texas charter schools had statistically significantly negative impacts on achievement (ELA and math) and significantly positive impacts on attainment (high school graduation). That’s a true mismatch, and cause for concern. But it’s just a single study out of 22.

Meanwhile, the eight studies that looked at college enrollment all found that test score impacts and attainment outcomes lined up: seven positive and one negative.

So is it fair to say, as the AEI authors do, that “a school choice program’s impact on test scores is a weak predictor of its impacts on longer-term outcomes”?

Hardly.

Where the debate goes from here

I’ve tried this week to keep my critiques substantive and not personal. I know, like, and respect all three authors of the AEI paper, and believe they are trying in good faith to help the field understand the relationship between short- and long-term outcomes.

What I hope I have demonstrated, though, is that their findings depended on decisions that easily could have gone the other way.

What all of us should acknowledge is that this a new field with limited evidence. We have a few dozen studies of bona fide school choice programs that look at both achievement and attainment. Most of these don’t examine college enrollment or graduation. That’s not a lot to go on, especially considering the many reasons to be skeptical of today’s high school graduation rates.

Given this reality, we should be cautious about making too much of any review of the research literature. I believe, as I did before this exercise, that programs that are making progress in terms of test scores are also helping students long-term. Others believe, as they did before this exercise, that there is a mismatch. Depending on how you look at the evidence, you can argue either side.

What we don’t have, though, is a strong, empirical, persuasive case to ditch test-based accountability, either writ large or within school choice programs.

Do impacts on test scores even matter? Yes, it appears they do. We certainly do not have strong evidence that they don’t.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)