In Alaska, an Education Activist is Trying to Unseat the House’s Longest-Serving Republican

One of the nation’s most intriguing congressional campaigns is unfolding in deep-red Alaska, where federal elections tend to hold few surprises.

Education activist and former teacher Alyse Galvin, an independent candidate who has won the Democratic Party’s nomination, is challenging Rep. Don Young, an icon in the state and the so-called Dean of the House as Congress’s longest-serving present member. The contest is a rematch of the pair’s tight 2018 race, when Galvin garnered a higher percentage of the vote than all but two previous opponents in Young’s 47-year tenure in the House.

It’s also being fought statewide — as one of the smallest states by population, Alaska elects only one at-large congressman — during a cycle that is projected to be a good one for Democrats. A recent poll conducted by the New York Times and Siena College found the incumbent leading by 8 points, but still beneath 50 percent, and respected forecasters have given Galvin a healthy chance at an upset on November 3.

While COVID-19 has torn most of the pages out of the traditional electioneering playbook, her odds will likely be bolstered by a strong campaign. Like many Democratic challengers both this year and during the 2018 midterms, Galvin has posted strong fundraising numbers. The 87-year-old Young, who has earned a reputation for off-color gaffes and occasionally head-scratching behavior (he once pulled a knife on former House Speaker John Boehner), hasn’t helped his own cause by dismissing the pandemic as a “beer virus” in a room full of senior citizens.

Amy Lovecraft, a political scientist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, said that Young’s familiarity to voters was a powerful asset that functioned “like the aura of a Supreme Court justice.” Still, she added, education-focused voters in the state’s relatively populous metropolitan areas of Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau could follow the lead of suburbanites nationwide by turning on the Republican Party.

“People like the idea that he knows the system,” she said. “But it’s likely to be closer [than in 2018], and there’s an off chance that Galvin could pull it out. What would have to happen would be a large upswell of voters, particularly in the Anchorage area, who maybe hadn’t normally voted but find education to be a significant issue.”

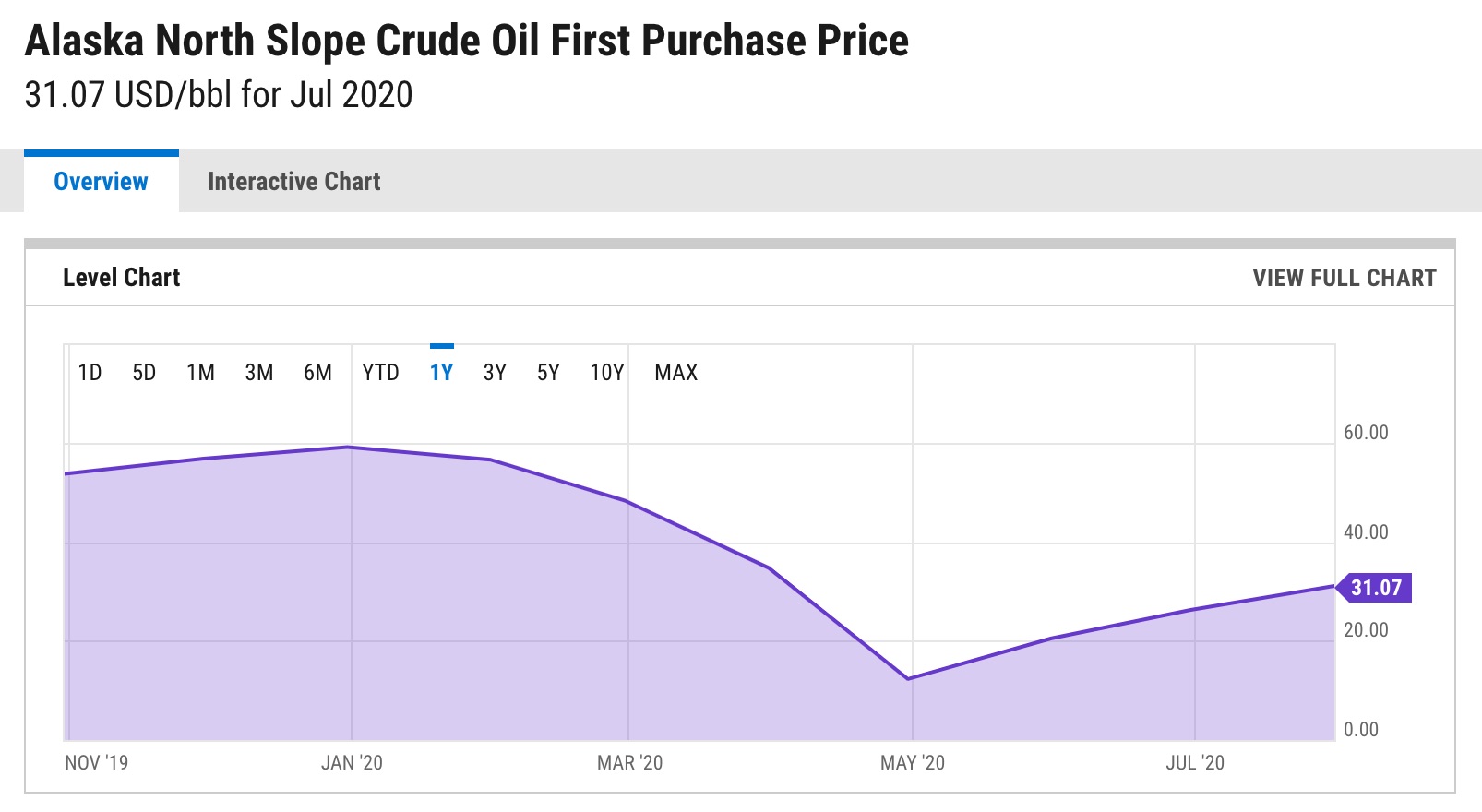

While neither candidate has made K-12 schools the centerpiece of their campaigns, they have nevertheless emerged as a major concern due to Alaska’s precarious financial situation. Even before the ravages of COVID, the state’s tax revenues fell dramatically in recent years due to a worldwide decline in oil prices. Funding for services like public education has been reduced by successive governors in an effort to improve the budgetary picture, but observers say that more cuts are likely in the offing.

It’s an atmosphere in which a known commodity like Young, with his decades of seniority on Capitol Hill, could be expected to prosper; along with the late Sen. Ted Stevens, he became legendary for earmarking millions of dollars of federal support for projects back home. But according to Diane Hirshberg, a professor of education policy at the University of Alaska Anchorage, the state’s close-knit political culture may mean that policymaking clout takes a backseat this year to the importance of personal relationships — like the kind Galvin has spent the last few years organizing around.

“Alaska,” Hirshberg said, “is a small town in a very, very big space.”

Bracing against school cuts

Galvin, whose campaign did not respond to a request for comment, is in many ways typical of the kind of candidate that Democrats have recruited to great success during the Trump presidency: female, moderate, and adroit on the stump.

She built her public profile on her years of advocacy as one of the leaders of Great Alaska Schools, a statewide coalition that has lobbied for more money for K-12 education. A former substitute teacher in Anchorage and a homeschool parent, Galvin says she’ll push for more federal resources for special education and early childhood development if elected.

Though she previously worked in state government, Galvin’s first significant taste of public notoriety came in the early days of 2017, when Betsy DeVos was being confirmed as Education Secretary. Great Alaska Schools organized a call-in campaign against DeVos’s nomination, along with in-person demonstrations at the local office of Sen. Lisa Murkowski. When Murkowski ultimately became one of just two Republican senators to vote against DeVos, Galvin took a victory lap in the national press that helped launch her 2018 candidacy.

Hirshberg, who has observed education policy debates in the state for nearly 20 years, remembered that the push against DeVos was “really a barrage” that had grown out of the group’s earlier campaigns against slashed school budgets.

“They’d created this really interesting alliance between urban, suburban, and rural parents that tried to have a statewide focus on maintaining support for public education,” she said. “At that point, it became really clear that the only way to transform that landscape was to change who’s in electoral office.”

The education cuts that initially brought Galvin and Great Alaska Schools into the public eye were largely the result of severe revenue shortfalls in the wake of a 2014 crash in oil prices. With no income or sales tax, the state’s operating budget is provided almost entirely from petroleum revenues that have steadily shrunk over the last half-decade.

“Revenue sharing to municipalities has been cut significantly, which has put huge pressure on local school boards to come up with the money to keep their schools running and repair buildings and hire teachers,” said Stephen Haycox, a local historian and columnist for the Anchorage Daily News. “Funding for rural schools, which are heavily dependent on the state, has been continually reduced. It’s really a dire circumstance for the state of Alaska at the moment.”

While former Gov. Bill Walker instituted some painful spending reductions in 2016, vetoing tens of millions of dollars in district debt reimbursements and school construction funds, the situation has grown vastly worse during the pandemic. With much of the industrial economy and national transportation brought to a standstill, the price of Alaskan crude plummeted from over $59 per barrel in December to just over $31 in July; according to some estimates, a change of even $1 in per-barrel price can swing up to $25 million in revenue.

The anxiety around depleted school finances has occasionally bred worry across the state, such as when proposals were floated in 2016 that would have doubled the minimum student enrollment for a school to receive state funding (a change that many feared would force dozens of rural schools to close. For Galvin, it offered a platform in her surprisingly strong 2018 bid to unseat Young. Lovecraft said that even in a losing effort, the first-time candidate and activist had made a strong impression on Alaska Democrats.

“She just hit a lot of the right notes, so I wasn’t surprised when they gave her a second run,” she said. “And she might get a third run because the Democrats aren’t thinking that, by funding her, they’re guaranteed a win. My hunch is that they’re grooming her and working with her because Don Young is old, and she could be someone they’re thinking about keeping in the wings.”

‘A good soldier’ for the GOP

Count Haycox among the skeptics who believe that Galvin, while “a very attractive candidate,” poses little threat to Young’s half-century reign as Alaska’s sole congressman. The incumbent’s longstanding ties to powerful groups like the oil industry, the Native community (along with stints in construction and commercial fishing, he taught at a Bureau of Indian Affairs school before beginning his political career) and even organized labor put him on highly favorable footing even against a talented opponent.

“Young is not sensitive” to any of the hot-button issues, from COVID to racial injustice, that have complicated the 2020 picture, Haycox said. “He’s a diehard conservative, he’s a good soldier for the Republican Party, and his special interest is in maintaining his alliance with his donors and attending to constituent issues. He’s been very, very diligent in helping people in Alaska get solutions to the problems that he could address.”

Others believe that the incumbent can’t count on his potent blend of seniority and name recognition to carry the day. Alaskans have long tolerated Young’s idiosyncrasies, including a well-known propensity for making profane and offensive utterances in public, in large measure because of his influence in the appropriations process. But Galvin’s campaign has argued that his influence has diminished in recent years, to the extent that Young — the longest-serving Republican congressman in history — is now barred by procedural rules from leading any committee or subcommittee on which he serves.

In a statement, a Young spokesman enumerated the congressman’s efforts to secure funding to fight family hunger, maintain rural schools and support homeless students.

“As a former teacher, a father, and grandfather, ensuring children have access to quality education is not just good policy for Congressman Young — it’s personal,” the statement concluded. “He will always stand up for students, parents, teachers and administrators. He will work with anyone, from any party, and provide serious consideration to all policy proposals that could strengthen our schools, support our teachers and equip our country’s children with the skills necessary to become leaders of tomorrow.”

Additionally, Young has assailed Galvin as a far-left activist attempting to bring socialism to the Last Frontier. In Facebook posts, he has linked his opponent with House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and accused her of trying to “trample our Second Amendment rights.”

The attack’s success, and whether voters come to see Galvin as an ideologue, may determine the election’s outcome. Like Senate candidate Al Gross, who has a puncher’s chance at unseating Republican Sen. Dan Sullivan on Election Night, Galvin is registered as an independent, not a Democrat. Though she won the party’s primary during both of her campaigns, and has accepted their open support, she has assiduously cultivated a nonpartisan profile as a way of competing in a deep-red state. That even included unsuccessfully suing the Alaska Division of Elections to keep the 2020 ballot from listing her as the Democratic congressional nominee.

Hirshberg lamented that the campaign’s hostile pitch did not allow for more discussion of K-12 issues. While Galvin sometimes spoke about her education proposals with supporters in virtual town halls, she said, the statewide discourse offered much less scope for nuance.

“Education’s in the mix in those intimate settings, but you don’t hear about it in the brash, outward-facing media war that’s going on right now.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)