In 2020, Virginia’s Legislature Passed a Transgender Students Rights Law. It Largely Hasn’t Been Enforced

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

In 2020, the General Assembly passed a law requiring local school divisions to adopt model policies extending rights to transgender students. But even as debates over those policies have convulsed school board meetings across the state and been debated by the candidates for governor, many districts remain out of compliance .

They’ve either rejected the Virginia Department of Education model policy outright or are adopting standards that fall short of the department’s guidelines.

In October, VPM reported that only two divisions in central Virginia have adopted policies that are fully consistent with the model. And at least six school boards, including Augusta, Bedford and Pittsylvania counties, have voted to explicitly reject the policy, according to tracking by Equality Virginia, an advocacy organization for the LGBTQ community.

“It really does have me scratching my head because these school boards need to be in compliance with state and federal law,” said Equality Virginia Executive Director Vee Lamneck. “And that’s what this guidance really helps school boards do.” The document lays out detailed steps for addressing the rights of students, from maintaining privacy about their transgender status (including from their parents, in the case of nonsupportive families) to developing gender neutral dress codes and allowing them to use the restrooms and locker rooms that align with their gender identities.

Beyond the fact that many districts aren’t following with the law, there also appears to be little, if any, enforcement. This summer, James Lane, the state’s superintendent of public instruction, sent a memo informing divisions that they assumed “all legal responsibility for noncompliance.” But the Department of Education doesn’t have the authority to assess penalties or otherwise pressure local boards to adopt consistent policies (the department isn’t even tracking which divisions are meeting the standards, according to spokesperson Ken Blackstone).

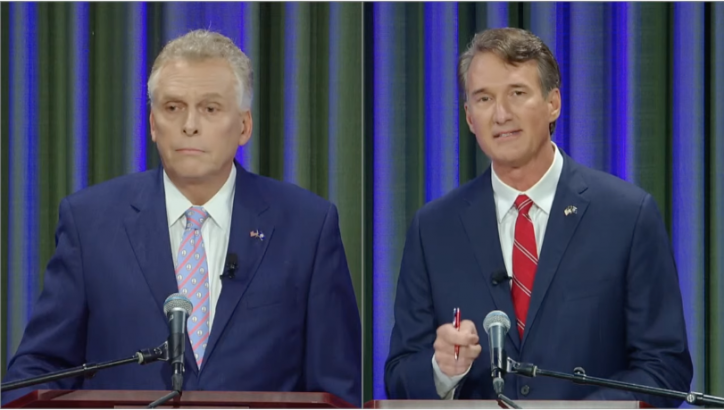

During a September debate, Democratic gubernatorial candidate Terry McAuliffe and Republican Glenn Youngkin both signaled that local school boards should have a large role in shaping policies on the treatment of transgender students.

“I’ve always felt that school boards have the pulse of the local community, they should be making their decisions,” McAuliffe said . He doubled down later that month, repeating in another debate that “locals” should have input on the issue (though the state “will always issue guidance,” he said).

Youngkin has gone a step further, saying parents should have a voice in the “dialogue.” But the 2020 law, at least as written, largely takes local choice out of the equation, requiring school boards to set policies that are consistent with — or even more comprehensive than — a model drafted by the Virginia Department of Education. The document offers specific recommendations on a wide range of policies, from using the names and pronouns students identify with to allowing them to use the restrooms that align with their gender identities.

Jack Preis, an associate dean with the University of Richmond School of Law, said the state attorney general does have the authority to proactively enforce state law. But it doesn’t appear that Attorney General Mark Herring is taking those steps. After the legislation was unsuccessfully challenged by conservative groups, one attorney with his office said the state would not withhold funding to divisions that failed to comply with the law, according to reporting by Courthouse News Service.

“I think DOE would be the best folks to talk to about how they implement and enforce their guidance and policies,” spokesperson Charlotte Gomer wrote in response to questions from the Mercury.

The attorney general, she said, “believes that all students in Virginia deserve a safe, welcoming learning environment where they feel supported and protected, and adopting DOE’s guidance or something similar will help with that goal.” But Gomer didn’t respond to additional follow-up questions about whether there were any plans for enforcement, or whether there were any potential mechanisms to drive compliance beyond withholding state funding.

With no incentives — negative or positive — for following the law, its impact and its future remain uncertain. Neither Youngkin nor McAuliffe have addressed whether their positions on local control mean they would support its repeal. Nor did they comment on whether local school boards should be required to follow VDOE guidelines. The Youngkin campaign did not respond to a request for comment, and McAuliffe spokesperson Renzo Olivari said only that the former governor “has been clear he will always protect students from discrimination.”

The issue has become especially resonant, though, amid a heated race that’s focused more on cultural flashpoints than concrete policies. Public education has been a dominant emphasis for both campaigns, with Youngkin billing himself as a defender of parents’ rights and McAuliffe accusing him of ginning up a “right-wing culture war.”

Glenn Youngkin wants to bring Donald Trump’s politics of hate and divisiveness to our Commonwealth and to our classrooms. If we come together, we can stop him. Get out and vote. https://t.co/ntElDYsRQT pic.twitter.com/UvmO5yOaZD

— Terry McAuliffe (@TerryMcAuliffe) October 28, 2021

Amid the debates, policies regarding transgender students have become as big a flashpoint as the ongoing outrage against so-called critical race theory — a largely academic term that’s been leveraged to criticize school equity efforts and lessons that incorporate historical racism. Earlier this year, there were arrests at a Loudoun County school board meeting where opponents openly criticized the district’s proposed transgender rights policy. The policy, which was ultimately passed by the board, again became politicized when the district was accused of covering up a sexual assault committed against a student in the girls’ bathroom of a local high school (the parents of the victim have claimed the perpetrator was was gender fluid, but no discussion of the perpetrator’s gender identity surfaced in the court hearing, according to The Washington Post).

Other boards have made headlines for rejecting the state’s guidelines or falling short of the required standards.

“It’s probably fair to say that some hesitation or resistance does come from pushback from parents and families who don’t want to see these policies adopted,” Lamneck said. But, they added, it can also stem from basic unfamiliarity with transgender people and the challenges they face.

Despite efforts by state legislators to move in the direction of more progessive school policies, Preis said there’s still hesitation from many school boards — and families — about issues like inclusive bathrooms and locker rooms. That’s despite the fact that denying students access to facilities that align with their gender identities has been interpreted as a violation of constitutional rights — largely through a court case brought by former Virginia public school student Gavin Grimm.

“I try to be honest about the fact that a lot of reasonable people are unaware and still learning about these things for the first time,” Preis said. Some local administrators also say the model policy doesn’t always match up with the needs or values of their school community. Keith Perrigan, the superintendent for Bristol City Public Schools in Southwest Virginia, emphasized that his district has “by no means” adopted the state’s guidelines, instead opting for a more general nondiscrimination policy that includes gender identity as a protected status.

It’s a route many local divisions have taken, according to VPM, and one that the Virginia School Boards Association says legally meets the requirements of the state’s law (JT Kessler, the association’s government relations specialist, did not respond to a request for comment). Del. Marcus Simon, D-Fairfax, who sponsored the original legislation, also said legislators were aware that the language offered few options for enforcement.

“We did know that should a school district basically give us the middle finger, there isn’t a whole lot to be done about it,” he said. “But the intensity of the backlash, and the decision to use this as a wedge issue, has been disappointing.” Without specific language to address compliance, Preis said the law is likely to be fought out in the courts system through individual lawsuits against nonconforming school districts.

The problem, Lamneck said, is that it shifts the burden onto already vulnerable students and their families. And beyond the hassle of fighting their school districts, they said it impacts student safety and wellbeing. General nondiscrimination policies don’t address many of the day-to-day challenges transgender students can face, like what to do if a classmate or teacher refuses to use the name or pronouns they identify with.

“It’s important for school boards to be in compliance with state and federal law, but we’re really talking about the quality of these kids’ lives,” Lamneck said. The failure to address enforcement could also have an impact on other recently passed legislation.

Earlier this year, state lawmakers passed a bill to require cultural competency training for all licensed school employees. The legislation again tasked VDOE with drafting guidance for school districts, but individual divisions are responsible for adopting and implementing their own training policies. Given the current climate surrounding critical race theory, it could become another political flashpoint for localities.

“The question really is, ‘Are we going to be entering another era of mass resistance for some of these localities?’” Simon said. “Which is the way I look at it. And if we are, if school boards have gotten so politicized, then we’ll have to look at what other tools are available other than passing laws and expecting government officials to follow them.”

This article originally appeared at the Virginia Mercury, part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Virginia Mercury maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Robert Zullo for questions: [email protected]. Follow Virginia Mercury on Facebook and Twitter.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)