Shango Johnson doesn’t know which side should be conceding more in the tug-of-war between Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Teachers Union over the expired teachers contract but he is pretty sure who is being pulled apart in the middle — kids in poor schools.

When the 44-year-old parent takes a close look at what he sees as the dim educational prospects of his South Side neighborhood, he knows city leaders should do whatever it takes to keep money in local classrooms—and fast.

“Someone needs to get more money…There are not too many adequate schools out there,” said Johnson, who works as a mentor to elementary school students in the city school system.

But that thirst for greater resources doesn’t necessarily translate into bigger paychecks for the 27,000-member CTU.

“Do I believe the teachers should get more money?,” he said. “I believe the schools need to get more money. I believe each school should get (more money), especially in Englewood.”

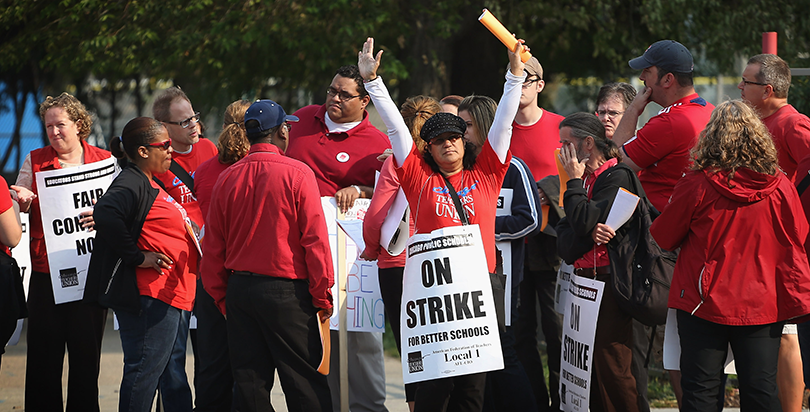

This week, the battle over what terms will ultimately shape the teachers contract forced parents, activists and principals to confront the reality of millions of dollars in cuts to city schools at a time when both the state and district’s finances are in crisis mode. As the power struggle has dragged on, parents and community activists told The Seventy Four they are worried it will ultimately hurt children’s education.

“The kids are the ones that suffer,” Johnson said. “I pray they can get together.”

How far the two sides are from getting together became more obvious Monday when the union’s 40-person “Big Bargaining Team,” unanimously voted to reject the district’s contract offer. The teachers contract expired last June and negotiations have been ongoing for more than a year.

That there was a vote at all signaled briefly to some that the district and the union had made progress after months of threats from Chicago Public Schools CEO Forrest Claypool that the district might have to lay off thousands of teachers if it didn’t get more money from state lawmakers or concessions from the union. Teachers, who walked off the job for nine days in 2012, have already voted in support of a strike though, under the law, that likely would not happen until mid-May.

“We have no trust in CPS. It fails to keep its promises,” union President Karen Lewis said. “We have dealt with a myriad of lies and financial myths that are designed to create a doomsday narrative and to provide them cover as they continue to proceed with their austerity agenda.”

Claypool called the offer, which

included small raises, greater

teacher contributions to pension and health care, a promise to curtail charter school growth and not inflict layoffs, a “true compromise that requires sacrifices from both sides so that we can protect what is most important: the gains our students are making in their classrooms.”

Alana Baum, a city parent

who has written about her support of the 2012 strike, said she was surprised to learn that the union rejected the latest offer. If the union doesn’t agree to a compromise with Chicago Public Schools soon, she worries that the alternative may mean the school system goes into bankruptcy—an outcome that would only hurt the neediest of students, she said.

“I think it’s become very clear the union needs to work with the city,” she said in an interview. “‘I’m scared for kids in this city. I think this deal has to happen.”

Erica Clark, a founder of the union-friendly

Parents 4 Teachers group, said parents know that good working conditions for teachers will positively affect their children’s education.

“I think most parents trust their teachers to do what’s best for their profession and their students,” she said. “We want our teachers to be well compensated, we want them to get a decent pension.”

Communities United, a grassroots activists group that focuses on social and economic issues on the city’s Northwest side, plans to hold a forum Wednesday evening in Albany Park for teachers, parents and residents to discuss the potential impact of the budget crisis and how they might find other ways to fund local schools.

“This is like opening the floor to teachers, parents, and students…to talk about how this is going to impact their education,” said Jessica Estrada, an education organizer for the group.

Debi Prince, a Lane Tech College Prep High School parent, said while she understands the difficulty of teaching, the city and state don’t have enough money to pay the full cost of teachers’ pensions. She said last week she was worried the contract negotiations won’t be resolved without a teacher’s strike, which would harm already-vulnerable students.

“I think the teachers want to strike,” Prince said. “I don’t want to hear ‘We’re doing it for the students.’ I’m 100 percent against that.”

On Tuesday, Claypool said that with no teacher contract in sight, the district would start having conversations with principals about $100 million in budget cuts it planned to make at the school level following another $45 million in cuts already made to the central office. Cuts to school budgets would also affect charter schools who rely on revenue from the district based on the number of students they have.

Claypool said that it would save another $170 million by no longer picking up 7 percent of the teachers’ contribution to their own pensions—a move the district said is allowed under the law even without a contract. In a letter to the teachers union, Claypool said the cuts would take effect in 30 days.

To put those figures in context, the school district

has previously said it has an ongoing $1 billion deficit but needs as much as $480 million to avoid massive cuts this school year.

“This is something I hoped to avoid at all costs,” Claypool said of the cuts. “We’ll do our best to prevent teacher cuts and will work with schools to keep class sizes small and prevent mid-year disruptions — but it means school support staff will be disproportionately affected.”

The Illinois Network of Charter Schools estimates that its schools will see a 4.3 percent loss to the last quarter of their annual budgets as a result of the district’s funding cuts. Andrew Broy, the network’s president, said his organization has been fielding calls from worried charter school leaders since Tuesday’s announcement.

“We’re very concerned about it,” he said. “The charter school community has nothing to do with CTU’s negotiation with the district,” adding that cuts to charter school budgets “come right out of the classroom.”

Shortly after Claypool’s comments, Lewis held her own press conference to announce that the union planned to file unfair labor practice charges with the Illinois Educational Labor Relations Board, hold a rally Thursday to support teachers and remove its money from Bank of America, which it contends is engaged in

imprudent interest deals with the school district.

“Due to their attack we have no choice but to express our outrage at this latest act of war by rallying against CPS and the bankers who are siphoning off millions from our schools and our children,” Lewis said.

“We will not be bought. We will not be bullied and the district cannot continue to betray us.”

And if that wasn’t contentious enough, Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner, a businessman who ran on a campaign to curb union influence in state politics,

told The Chicago Sun Times Tuesday that the state was preparing to take over the school district because the city could not negotiate a contract with the union.

Two Republican lawmakers have already

proposed legislation that would allow the state to take over the district and for the school system to declare bankruptcy though they face an uphill battle in a

Democratically controlled state legislature.

Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Lewis found common ground in offering sharp rebukes to the idea of a state takeover of the city’s public schools, noting that Rauner hasn’t managed to pass his own state budget as he rejects proposals from Democratic lawmakers.

“At least a large part of their common enemy is the state,” Dick Simpson, a former city alderman and politics professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago, said of the two sides. “They really have more in common in struggling with the state than in the fight with each other.”

Simpson said the state’s financial situation may improve after the March primary election, when the governor would no longer be able to financially back any opponents to Republican lawmakers who are willing to compromise with Democrats on Illinois’ budget. In theory, those lawmakers could also work on a deal to help Chicago Public Schools’ revenue problems, Simpson said.

“I still wouldn’t be surprised to see an agreement worked out (on a new teachers contract)” he said.

Johnson, the Englewood parent, said he is hopeful that any deal ending the strife won’t force schools on the South Side — already suffering from crumbling buildings and financial abandonment — to slash their budgets even more.

“I know right now it’s hard in the state in Illinois…,” he said. “I just know that it should be fair.”

;)