‘I Was the Lucky One’: School Shooting Survivor Shares Story at L.A. March

Mia Tretta is working to outlaw so-called “ghost guns” like the one used in the 2019 shooting at Saugus High School

Dominic Blackwell was one of the first friends Mia Tretta made when she moved to the Santa Clarita Valley, near Los Angeles, in 2018.

“He had this infectious laugh,” she told The 74.

The two were walking through the quad at Saugus High School on the morning of Nov. 14, 2019 — Tretta remembers being nervous about a Spanish test — when she heard a bang. A second shot struck her in the abdomen, knocking her to the ground. Blackwell and another student were dead and two other students were injured. The 16-year-old gunman, a student at the school, shot himself in the head and died the next day.

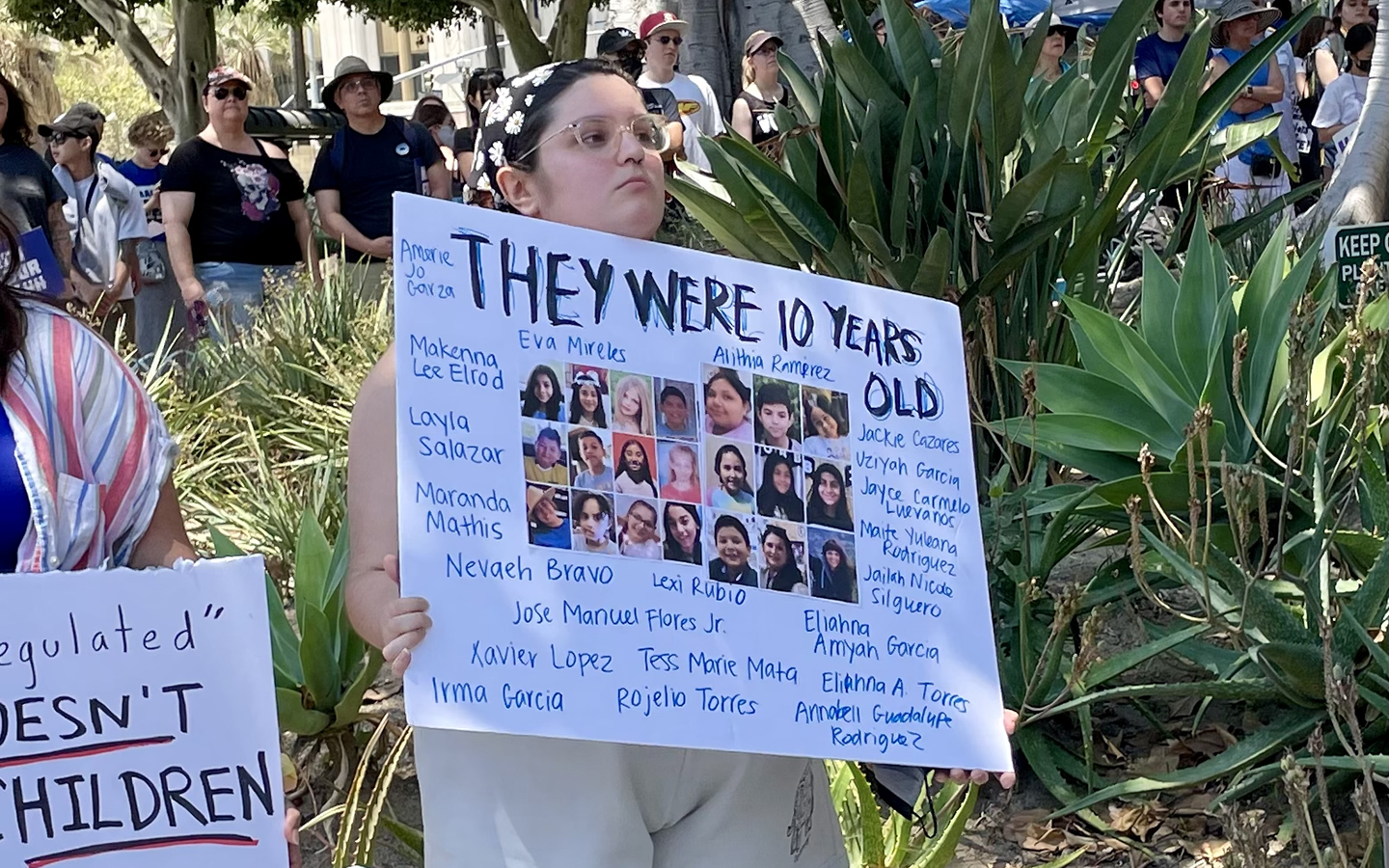

On Saturday, Tretta told her story as a crowd in blue March for Our Lives T-shirts, lifting homemade signs above their heads, filled the grounds outside Los Angeles City Hall in one of hundreds of demonstrations across the country.

March for Our Lives organized the protests after the recent mass shootings at a grocery store in Buffalo, New York, and an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas. But the turnout at the L.A. rally — several hundred — and nationally didn’t match the massive showing in 2018.

“Compared to my friend, Dominic, I was the lucky one,” said Tretta, standing in the bed of a pick-up truck used as a makeshift stage. Tretta has focused her advocacy on outlawing “easy to assemble” weapons, known as ghost guns, like the .45- caliber semiautomatic handgun used in the shooting at her school.

In April, the rising senior spoke at the White House when President Joe Biden announced a new rule meant to close a loophole in gun laws by classifying “buy, build, shoot” kits as firearms and requiring the parts to have serial numbers.

“The loopholes are as wide as the Grand Canyon,” she told Saturday’s crowd, “and the current safeguards are simply not enough.”

Tretta’s path as an activist has been different from that of the survivors of the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, who mobilized students to walk out of their classrooms and organized the 2018 march in Washington D.C. that drew roughly a million participants.

Not long after the Saugus shooting, the world shut down for the pandemic.

“That was difficult to watch her try to find her voice over Zoom,” her mother, Tiffany Tretta, said Saturday.

Aside from the emotional trauma Mia carries, her injuries left lasting physical damage, her mother said. Because of her injury, her daughter became immunocompromised and had to take extra precautions to avoid COVID, like staying away from crowded events. She found out last fall she had a hole in her ear drum that causes ringing. She couldn’t hear low-frequency sounds and loud noises caused pain. She’s had to have injections to stop the pain that shoots down one of her legs.

Mia works with Sandy Hook Promise, which trains students and adults to recognize signs that someone might be planning a shooting, and Everytown for Gun Safety, which advocates for gun control legislation. She formed a Santa Clarita Valley chapter of Students Demand Action, an organization with over 400 chapters that sprung up after Parkland.

Last month, after the shooting at Robb Elementary in Uvalde, Texas, about half of the students at Saugus walked out of class in protest. Several of them took part in Saturday’s march.

“I hope there’s more outreach,” said Kate Nilsen, who will also be a senior this fall. “The more the people, the louder the voices.”

After the rally, the crowd, chanting “Vote them out” and “I’m fired up” followed a square route through downtown before returning to hear more speakers.

Katie Cimino, a preschool teacher for 16 years, drove over 50 miles from Riverside County to join the march.

“I’m having to teach my babies how to be safe, and it’s messed up,” she said.

Despite the crowd’s enthusiastic response to the speakers, Cameron Kasky, a Parkland survivor who organized the original march in Washington, said his generation is frustrated.

“A lot less people have turned up in 2022 because we all feel there’s nothing we can do,” he told participants, placing some of the blame on Democrats. “I don’t see anything coming from these people.”

On Sunday, senators announced a tentative bipartisan deal on gun safety that includes spending on community mental health care and school security, encouraging states to pass “red flag” laws that keep guns away from those who pose a threat and preventing gun sales to domestic violence offenders.

In a statement, President Joe Biden said, “Obviously, it does not do everything that I think is needed, but it reflects important steps in the right direction, and would be the most significant gun safety legislation to pass Congress in decades.”

Kasky also grew irritated with vendors who set up tables on the sidewalk Saturday to sell March for Our Lives merchandise — flags at one for $10, three for $20. He argued with them before the rally, and the tables were moved down the block after police intervened.

“Grifters always show up to make money off our causes,” he said.

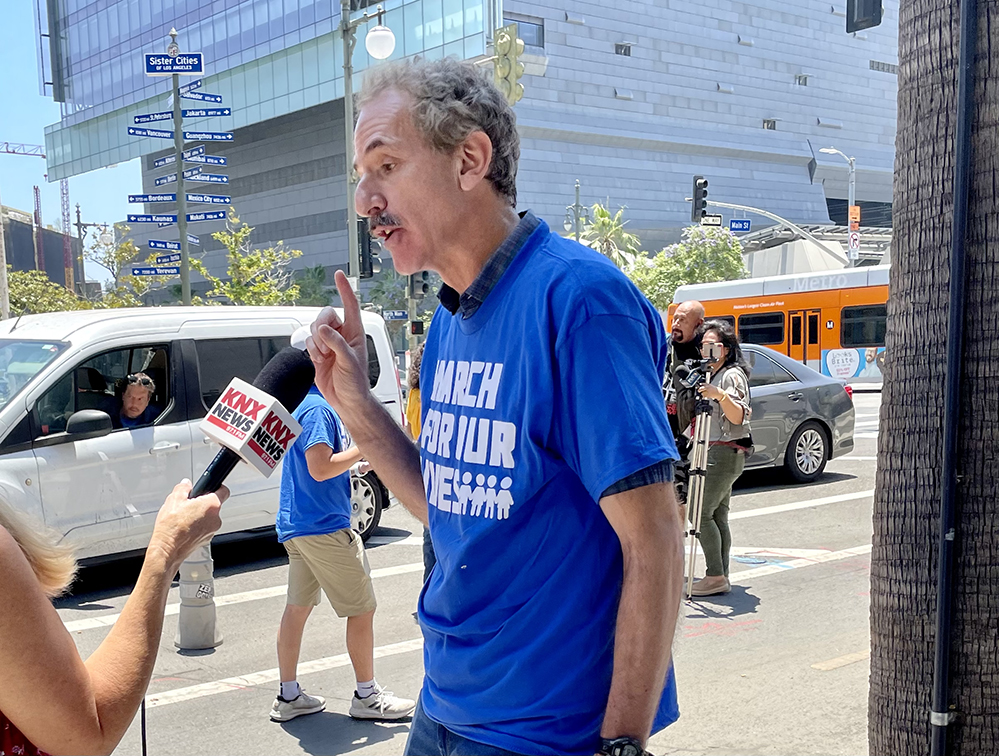

Like Kasky, Mike Feuer, Los Angeles city attorney, took action after the Parkland shooting, creating a “blue ribbon panel” on school safety. He was on hand again Saturday to push for more change.

The panel issued 33 recommendations, including the creation of a single point of entry for every school, encouraging parents to safely store guns at home and increasing “safe passage” programs that protect students on their way to and from school.

“The issue of violence requires us to fire on many cylinders at once,” he said.

He said he’s discussed the issue with Alberto Carvalho, Los Angeles Unified’s new superintendent, who recently told The 74 that he plans to have “a conversation with the board” about the district’s 2021 decision to reduce the number of school police officers on campus.

Just after the Uvalde shooting, on June 1, a student was shot outside L.A.’s Grant Senior High School.

But Feuer said the role of law enforcement at schools needs to be clear.

“It’s not that we should be over-policing students,” he said. “We should be doing the opposite.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)