How YouCAN Is Growing Grassroots Education Leaders to Improve Their Schools and Communities

When first-grade teacher May Amoyaw wanted to start a grassroots education project in her Baltimore community, she knew the idea couldn’t come solely from her.

“I’m not originally from Baltimore, so I didn’t feel like it was my job to go in and create something for them,” Amoyaw said. “I really wanted to elevate the voices that were already there. If you guys are already doing it, great, let’s get together, let me add my part, and let’s do what we can for our neighborhood.”

Amoyaw’s belief in this approach was further supported through her advocacy training with YouCAN, a program begun last year by education reform nonprofit 50CAN to develop community education leaders across the U.S.

Through YouCAN’s training, Amoyaw learned to build and connect systems already in place. She created a parent advisory council and conducted a listening tour to hear about community education problems and efforts to address them.

(The 74 Exclusive: Ed Reform Groups StudentsFirst and 50CAN to Merge)

50CAN already had an Education Advocacy Fellowship program, but the desire for training in how to effect community-driven change far outstripped its capacity: When the organization introduced the paid, year-long program in January 2015, it received nearly 800 applications for just five spots.

So 50CAN started YouCAN, which is more cost-effective and can accept more applicants. Starting with a two-day orientation in Washington, D.C., the 11-month program helps advocates create education-oriented projects and provides training, one-on-one mentoring, and peer support.

As the second class of YouCAN fellows begins this month, projects started by last year’s trainees are going strong. From addressing illiteracy to retaining minority teachers in the classroom, here’s a look at some of the solutions YouCAN advocates have cultivated.

Literacy: Not just for early learners

Kesha Lee, a longtime education proponent, had known that literacy was an issue for families in her southeast D.C. neighborhood. But she saw an unexpected hunger for reading when she tried to start a lending library in a local barbershop. After delivering 400 books, she left for vacation. When she returned, all the books were gone.

“I talked to the owner, and he said, ‘Kesha, the kids kept asking me, “Can I keep them?” and I didn’t have the heart to tell them no.’ ” Lee said. “I said, ‘OK, that’s a good problem to have.’ ”

In Washington, there’s a huge disparity in the access that people in different neighborhoods have to buying books. A 2016 study about book deserts examined the literary resources for sale across neighborhoods and revealed that in southeast D.C., there was one book for every 830 children — but the wealthier Capitol Hill neighborhood had one book for every two kids (this does not include library books).

For her YouCAN project, Lee wanted to address this literacy inequality. But she didn’t want her work to be limited to one group of learners. Instead, she wanted to show how poor literacy promoted systemic inequalities across all ages. In her neighborhood, younger children don’t have access to books, an average of only 3 percent of middle and high schoolers are proficient in reading, and the illiteracy rate among people over 16 has been as high as 50 percent. Such literacy gaps create barriers between blue-collar and middle-class jobs.

“Why aren’t people more angry? Why aren’t we more upset about this?” Lee asked. “Especially the fact that we live in D.C., which is the tragedy of all this: It’s one of the more highly educated cities in the U.S.”

To raise awareness, she is launching a website that can serve as an advocacy space. She has mapped out plans to submit op-eds to major media publications and is considering advertising on public transportation. She’s also attending local community meetings to make her pitch on why this issue needs more attention.

One focus is connecting existing organizations and raising awareness of resources that are already available but aren’t advertised well in the neighborhood. For example, Lee said, many parents aren’t aware that they can register for D.C.’s Books From Birth program, which sends a free book each month to every child age 0 to 5 who lives in the District.

Also receiving focus are the lending libraries that inspired Lee’s work in the first place. Three libraries are operating in neighborhood barbershops now, and she hopes that through her new website, the community can help decide where the next ones should go. Through a YouCAN crowdfunding project, she’s already raised $2,000 for new books.

Building an oasis in a food desert

Every day, May Amoyaw would watch her first-graders arrive at school with soda, candy, and Cheetos for breakfast. She knew they hadn’t bought junk food because they craved artificial flavorings — none of the grocery stores within a mile of the school sold the kinds of healthy snacks that Amoyaw sometimes purchased for the kids with her own money.

Those students were on her mind when Amoyaw signed up to be a YouCAN advocate. She didn’t know what she wanted her grassroots education project to entail, but she knew she wanted to connect what was often referred to as “the two Baltimores”: the parents and students with the policymakers. Most important, she wanted the community’s voice, rather than her own, to lead the discussion.

But the issue of food deserts kept coming up as something people in the community wanted to change — and some were already trying to. When Amoyaw talked with Councilman Kristerfer Burnett, she learned about the Edmondson Village Farmers Market, which was created specifically to address the neighborhood’s food desert.

So Amoyaw asked if she could add a youth component, having students grow fruits and vegetables and sell them at the market.

Amoyaw connected with the Edgewood-Lyndhurst Recreation Center, where many students played basketball as they waited for their parents after school, and had eight raised garden beds constructed outside for what’s now called the Blade Project.

The farmers market won’t reopen until the spring, but Amoyaw is already envisioning a larger future for the Blade Project.

“My big vision is, I hope that every school will have fresh produce that is grown by the students themselves,” she said. “There’s something very powerful about doing something yourself versus going to Giant and picking it up.”

With hydroponic techniques that allow food to be grown without soil, Amoyaw also hopes students can start gardening at home.

Minority teachers make the difference

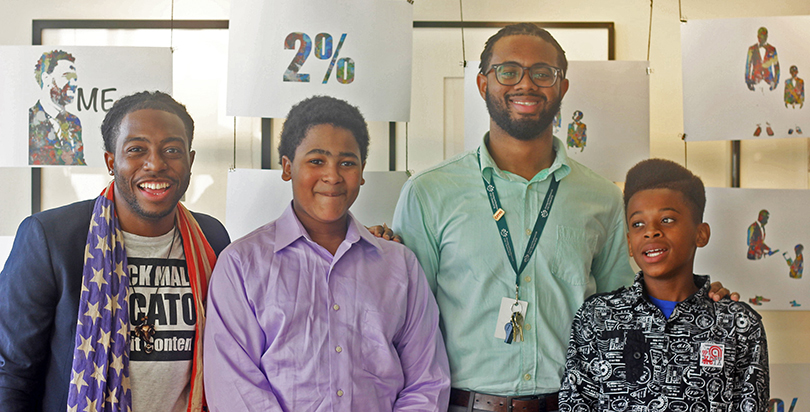

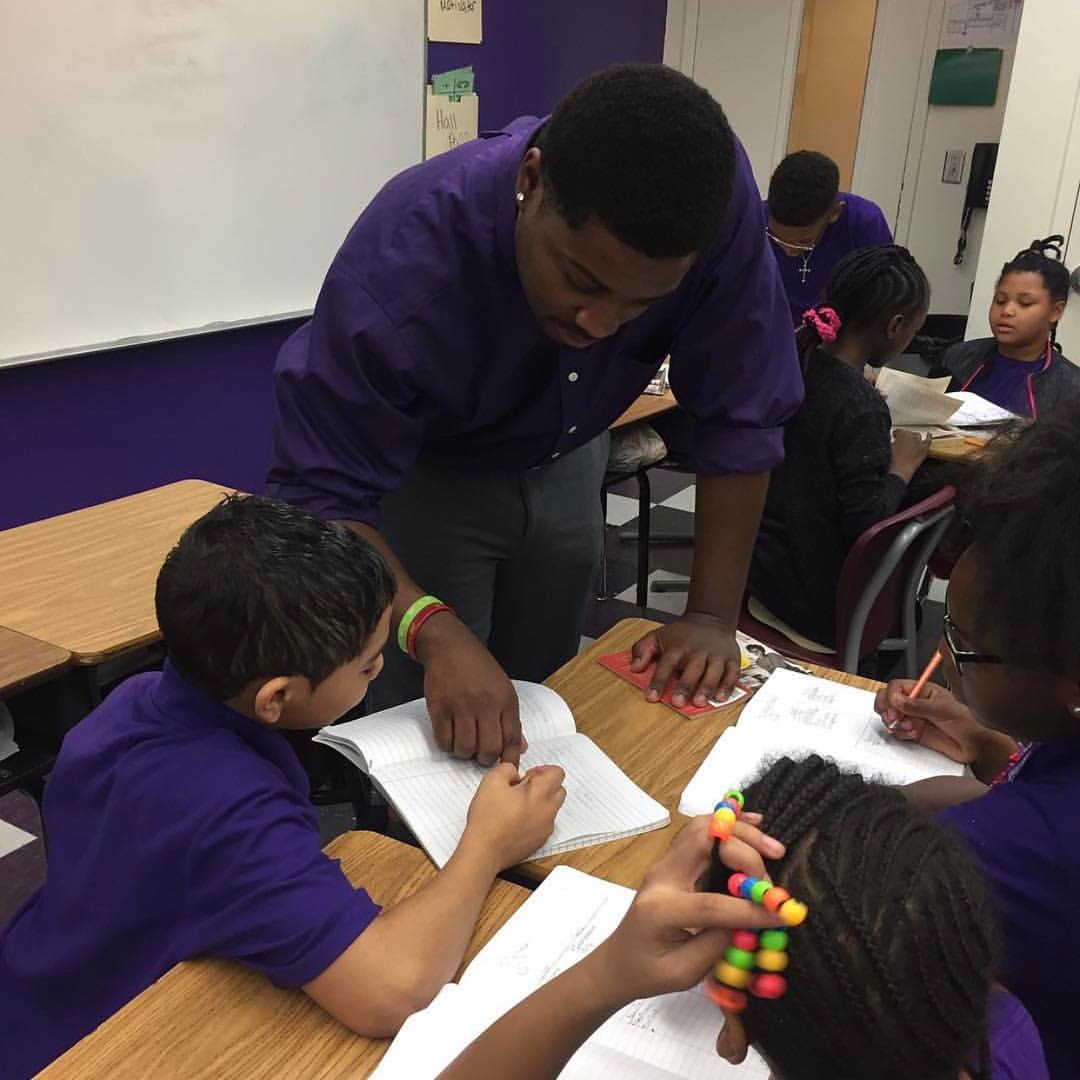

Jason Terrell never taught Jalen, a middle-schooler at his school in Charlotte, N.C., but every day Jalen would come find Terrell — before school, during class, after school — just to talk. Jalen was a repeat student and had disciplinary issues, but he found a mentor in Terrell, one of the few educators in the school who looked like him: a black male.

Research shows that when student demographics are mirrored by their teachers, achievement scores improve. But while schools have gotten better at recruiting minority teachers, their ranks have grown at a slower rate than the population of minority students. And as difficult as it is to recruit minority teachers, retaining them is even harder.

Terrell and his Teach for America roommate Mario Jovan Shaw both felt the frustrations of being among the few black male educators in their schools. They were often called on to fill disciplinary roles or coaching spots, but rarely for curriculum or professional development. So they started Profound Gentlemen in 2014 with the goal of retaining enough men of color in schools for students of color to engage with.

“People are becoming more receptive to keeping the teachers in the classroom, making sure they have the best development opportunities possible instead of just getting teachers in the door,” Terrell said.

He said he hopes to connect male educators of color both with their professional peers and with their students. The nonprofit Profound Gentlemen network has 150 member educators who create mentorship groups at their schools. These groups can be incorporated into a sports team or developed from scratch. The goal is for the group to work on social-emotional learning activities for at least two hours a month, discussing things like handling trauma, stress, or anger. And with grant money from YouCAN, Profound Gentlemen can give financial support to some of those projects.

“In my time as a baseball coach, I never had, really, the conversation around how to manage your anger with my baseball team. I didn’t even think of it,” Terrell said. “I wish I would have had an opportunity to have conversations with my group of guys. I think I would have had even more of an impact on them beyond the sport.”

Terrell and Shaw also created an app to help educators connect with one another, explore different mentoring programs, and share advice. And they want to begin supporting professional development opportunities.

“At the end of the day, before they can be mentors in their school, they have to be killing it in the classroom,” Terrell said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)