How Schools and Programs Around the Country Are Making Teaching More Diverse

A new FutureEd study identifies a range of programs with promising strategies for making the profession more representative of the nation's students

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

As a little girl growing up in El Salvador, Aracely Valdes loved school and dreamed of becoming a teacher. Yet, when she enrolled in the Fort Worth, Texas, public schools at age 15, a new immigrant who spoke no English, the path to fulfilling her dream was far from clear.

Then, in her final year at Tarrant County College, Valdes saw a flier for a 12-month program called Tech Teach Across Texas that would let her earn a teaching degree while being paid to serve as a classroom trainee. The Texas Tech University program was designed to address the state’s growing demand for teachers and widespread dissatisfaction with instructors coming through alternative certification programs that provided little classroom experience.

Texas Tech’s program allows community college graduates like Valdes to earn both a bachelor’s degree and a teaching certificate by combining online courses with a year-long paid classroom residency working under an experienced mentor.

Today, a year after completing the program with honors, Valdes is a dual-language third grade math and science teacher at T.A. Sims Elementary School in Fort Worth. As a bilingual educator of color, she is a much sought-after hire in Fort Worth and beyond.

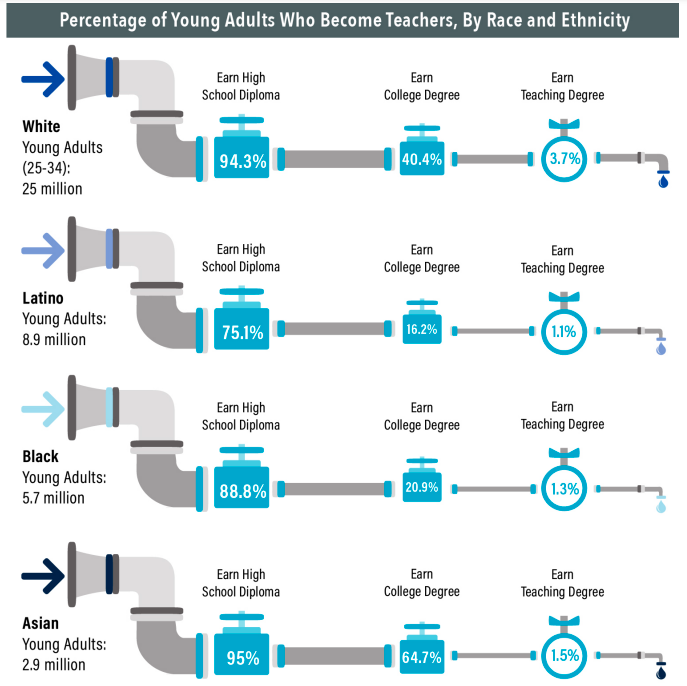

A host of studies have found that when students of color have teachers of color, their attendance improves, disciplinary infractions decline, and academic achievement and college enrollment rise. For all students, having a diverse teaching force strengthens confidence in their own abilities and improves racial attitudes. Yet, while students of color comprise more than 50% of public school enrollment nationally — a share expected to grow steadily in the years ahead — nearly 80% of teachers are white. In many states, this lack of diversity means students frequently attend schools and districts that do not employ a single educator of color.

A new FutureEd study of teacher diversity identified a range of programs, like the Tech Teach residency, that offer promising strategies for making the profession more representative of the students in the nation’s schools.

Setting measurable goals for recruiting, training and hiring candidates of color is a key first step. That includes publicizing goals and policymakers’ progress toward achieving them at the state, district and school levels. The federal government can contribute by requiring states to report on the racial and ethnic diversity of students who complete teacher-preparation programs.

Rather than waiting to begin recruiting teachers of color at the college level, some districts are encouraging middle and high schoolers to explore teaching careers. The Center for Black Educator Development, for example, partners with districts to create high school teacher academies that offer prospective educators a three-year curriculum centered on the Black experience. In Philadelphia, that means high school juniors and seniors can take college courses and graduate with an associate degree in education along with a diploma.

There’s also an opportunity to tap into local talent via Grow Your Own programs that provide pathways for paraprofessionals and other workers in the community to get the training and experience they need to become teachers. California’s Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing program, for example, has helped more than 2,000 teachers’ aides or paraprofessionals become teachers, nearly half of them Latino. Some programs take the form of teacher residences — like the one Valdes participated in — and apprenticeships, which are particularly promising for candidates of color, as they can receive extensive clinical preparation and earn a salary while they learn to teach.

The National Council on Teacher Quality has identified nearly 90 programs that are helping potential educators of color navigate a substantial barrier to the profession: state licensing exams. Candidates of color typically fail these tests at much higher rates than other teaching candidates. But at these programs, there’s little or no racial disparity in first-time pass rates, thanks to the support they provide to help candidates fill gaps in their content knowledge. Massachusetts is piloting a program that lets candidates substitute another approved standardized test for the state’s general knowledge exam for aspiring teachers. It also permits candidates who come very close to the passing score on subject-specific tests to submit an essay to demonstrate content knowledge.

Making a diverse teacher workforce an explicit priority in school district hiring also makes a difference. Highline Public Schools in Washington state, where more than half of the 18,700 students are Black and Latino, implemented an interview process designed to elicit candidates’ beliefs about teaching disenfranchised students and to identify implicit bias. Together with other steps, the strategy tripled Highline’s new hires of color from 12% in 2014-15 to 36% in 2022-23.

But it’s not enough to hire more teachers of color if they don’t stay, and many don’t. Attrition is significantly higher among Black teachers than whites and slightly higher among Latino teachers than whites. Leadership opportunities and clear career pathways for teachers of color can help address the problem. The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education has launched a fellowship program, Influence 100, to increase the percentage of superintendents of color over a decade. Another strategy is to connect teachers of color with peers, both locally and nationally, through paid, mentorship and professional learning opportunities. Highline Public Schools, for example, has created eight teacher affinity groups dedicated to racial equity and pays teachers to participate in them.

A comprehensive approach to increasing the percentage of teachers of color in the nation’s schools, pursuing diversity throughout the teacher pipeline, yields the strongest results. That requires a wide-ranging commitment among educators and education leaders. “Institutions of color and people of color are [often] burdened with solving the problem, one they didn’t create,” Anthony Graham, provost of Winston-Salem State University, said in an interview. Addressing teacher diversity, he said, needs to be “our problem collectively.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)