How My California Middle School Uses Glyphs to Teach English Learners to Read

Principal's view: Many have few or no phonics skills, and some never went to elementary school. They lack the basics even in their home language.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

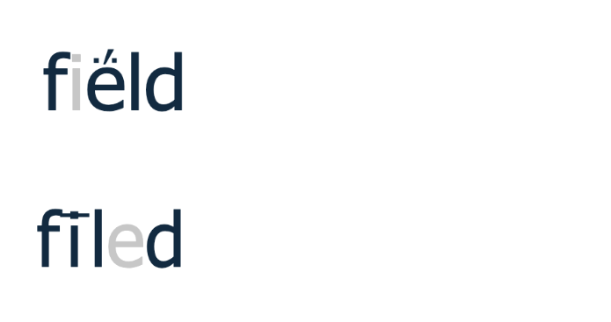

In the agricultural regions of California’s San Joaquin Valley, schools like Firebaugh Middle School are surrounded by fields. But many of Firebaugh’s students struggle to read that word. If they were to see “field” on the board, they would likely pronounce it as “filed,” a reflection of their unfamiliarity with the varied pronunciations in English.

Firebaugh’s student body is 98% Hispanic, and about 30% of its 530 sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders are designated as English learners. Based on diagnostic testing, administrators know many of them have limited or nonexistent phonics skills. In some cases, the students did not attend elementary school and lack the basics of literacy even in their primary language.

If you think of reading as an equation with specific components, you might assume reading instruction is straightforward. But as with any equation, there are variables, and English learners have many of them, from Individualized Education Programs to a diversity of home languages that makes it difficult for teachers to find a starting point for reading instruction. Any supplemental instruction educators provide must be flexible enough to account for those individual differences.

This is hard enough at the elementary level, but in middle school, students do not merely need to know how to read; they need to know how to read well, so they can comprehend information, analyze it and synthesize it. But in most middle schools, educators likely do not have comprehensive training in supporting basic reading development. While they may have picked up some strategies, their job and focus is to teach a single subject‚ not literacy. I’m a perfect example. I was a history major, and I am credentialed in social science. I was trained to teach ancient civilizations, modern government and economics, and everything in between — but not reading.

Time is also a limiting factor. At Firebaugh, students rotate through a seven-period school day. Teachers cannot adapt their schedules the way elementary educators can, making it challenging to spend extra time catching up students who are not reading at grade level.

We had attempted many approaches to improving literacy at Firebaugh. We added English language development classes. Educators tried to emphasize reading strategies and target specific students who were two or more grade levels behind in literacy. However, none of these efforts proved effective. Along the way, we realized many students needed pieces of the reading equation that we did not know they needed, such as decoding words.

Then, we discovered an unusual approach to adolescent literacy that uses glyphs as a resource to foster reading fluency and boost comprehension for English learners. The system consists of 21 glyphs, or diacritical marks, that function as a pronunciation guide for each word. These marks (think accents or umlauts) are widely used in languages other than English to aid with pronunciation and comprehension. The system indicates which letters make their usual sound, which make a different-than-usual sound and which are silent. It also denotes syllable breaks.

We implemented this glyph approach for English learners who had no experience sounding out words. In the first stage of implementation, students worked with teachers to learn the glyphs and complete core skill-building activities. In the second stage, the diacriticals — which are available for more than 100,000 words — were integrated into students’ daily reading practice to build fluency and comprehension. With the markups, words like “field” and “filed,” for example, were no longer a problem.

Initially, we wondered whether learning a whole system of markups would be worthwhile for the students. Over time, we saw that it really did expedite their progress. Now, the students understand the different types of sounds that the same letters make alone or in pairs. They pronounce words more accurately. Perhaps most importantly, they are more confident. They want to read.

An unexpected benefit was the assurance this approach gave our teachers. Those who had felt unsure about buttressing basic reading skills found a common support mechanism.

During the first full year of implementation, we saw payoffs across the board. When we looked at assessment data from fall to spring, we saw a 10 to 15 percentage point reduction in the number of students scoring two or more grade levels below standard, compared with no change under the previous program. Additionally, progress toward students’ individual goals was tremendous. For example, one student was working with a case manager on a list of 20 words. Without the glyphs, he was able to read two. With them, the student got 18 of 20 words correct.

Results like that have convinced our students to buy into this approach. They are willing to invest time in learning the glyphs and practicing daily. The program also serves as a cultural bridge, connecting with parents who don’t speak English at home because the symbols are similar to those used in their language.

We are confident we will continue to see a decrease in the number of students reading below grade level as we consistently implement these new reading strategies. As we enter the second year of implementation, we also expect to see a related trend upward to our English Language Arts scores.

Going forward, one of our goals is to establish a culture of reading within the school. Firebaugh’s students are at a stage when they are starting to become independent and make important life choices. This is a prime opportunity to position them for the future by providing them with an independent resource to support their reading progress.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)