How Leaked School Security Maps Could Put Minneapolis Kids in Danger

Sensitive, detailed campus security information was leaked after the district suffered a massive ransomware attack. School safety experts are alarmed

By Mark Keierleber | May 15, 2023As a visitor approaches the front entrance of a Minneapolis elementary school, their every move is documented by a security camera. A second camera positioned on the right picks them up as they walk down the hallway and a third keeps a watchful eye as they pass by the gym.

The specific locations of the campus surveillance cameras, and other sensitive details about the school’s physical security infrastructure, are attainable without ever stepping foot inside. That’s because they’re now readily available online, an investigation by The 74 has found. Security experts said the startling revelation puts students and staff citywide at risk of physical danger at a moment when mass school shootings have reached record highs, including a March attack in Nashville where police say the shooter relied on a hand-drawn map.

“Folks are already on edge with what’s been going on in schools and the fact that they got all of the security information and then think about who has it,” said Marika Pfefferkorn, a Minnesota-based student privacy activist and executive director of the Midwest Center for School Transformation. The information, she noted, is already in the hands of known threat actors. “At any moment, we’re just vulnerable.”

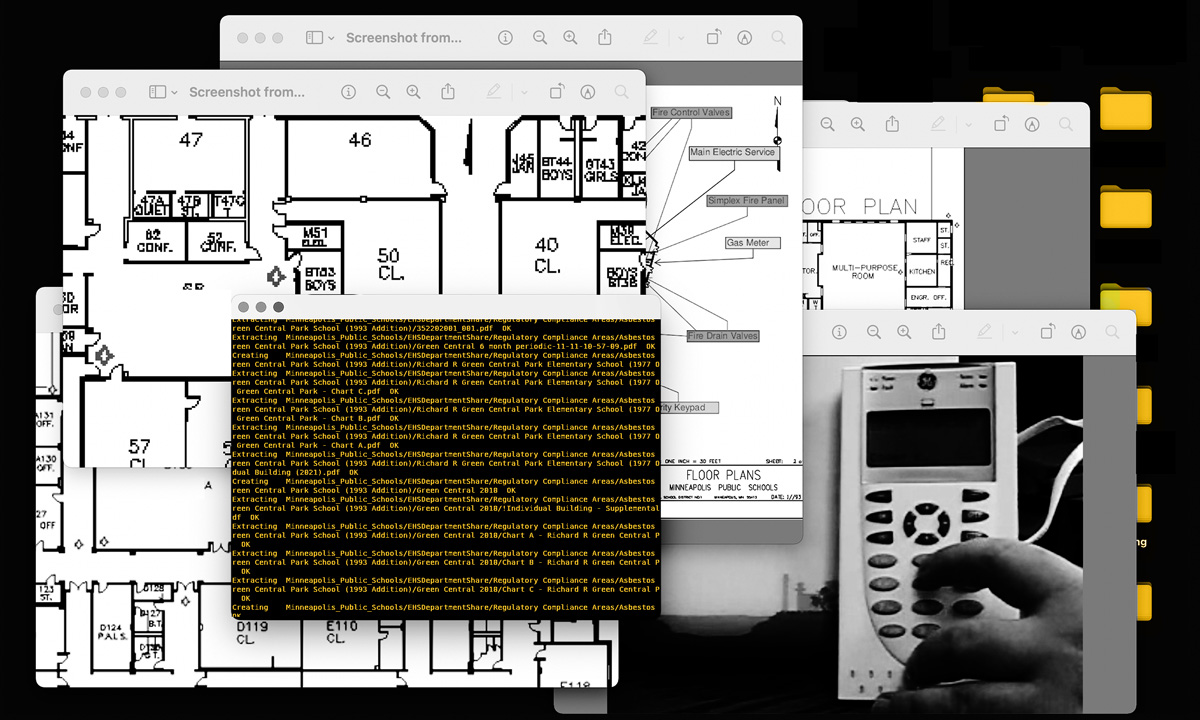

The school security records, including blueprints of campuses citywide, were uncovered in an analysis by The 74 of confidential files purportedly stolen from the Minneapolis school district by the ransomware gang Medusa. The records were published online in March after the district refused the cyber criminals’ demand for $1 million to keep the highly sensitive information from becoming public. The data encompasses more than 189,000 individual files totaling 143 gigabytes. The records, which outline specific, technical details about security systems in Minneapolis schools, can be downloaded with little more than a Google search.

States nationwide have ramped up efforts to digitize their campus security layouts, and since the mass school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, last year, several have rolled out multi-million dollar digital map initiatives in hopes they help improve police response times.

Along with insight into campus layouts and surveillance camera placements, the leaked Minneapolis records pinpoint the locations of fire alarms, security keypads, gas meters and water shutoff valves. Videos and PowerPoint presentations offer instructions on how to arm and disarm a campus alarm system. Maps document the routes that children are instructed to take should an emergency force them to evacuate their buildings.

In an email, district spokesperson Crystina Lugo-Beach declined interview requests from The 74. She said a third-party company is “meticulously reviewing all the documents released by the threat actor” and that the district has “not yet been provided with the results of that review.”

“This has been, as you know, an incredibly difficult situation for our community,” she continued. ”With accurate, comprehensive information, we will certainly make any necessary updates to our safety protocols.”

Given the sensitive nature of the campus security records, they’re generally inaccessible to the public. Under the state public records law, government records related to “security information” are explicitly exempt from public disclosure. This shields documents, including those maintained by public schools, that are “likely to substantially jeopardize the security of information, possessions, individuals or property.” Government entities typically apply a broad interpretation of the exemption to withhold records, said Don Gemberling, a Minnesota Coalition on Government Information board member who spent three decades in state government helping public agencies comply with the Data Practices Act.

“The kind of things you’re talking about, if you went and asked for it they’d tell you that you couldn’t have it,” he said.

Gemberling, who lives in Saint Paul, said the school district must move quickly to reconfigure its security systems.

“I’d be changing the location of cameras, I’d be making sure that every door that indicates some kind of vulnerability is fixed,” he said. “I’d sure be looking at where my security software failed because it appears to have failed miserably.”

The Minneapolis schools breach also exposed confidential and highly sensitive records about individual students and teachers, including files that outline campus rape cases, child abuse inquiries, student mental health crises and suspension reports. Some of the sensitive files are from earlier this year, though many of the campus security records are undated and it is unclear which details remain accurate.

For individual students and educators whose sensitive information was published, the data breach could have serious, long-term ramifications, said school cybersecurity expert Doug Levin. Yet even taking into account that disturbing consequence of the breach, the release of campus security records presents a serious escalation.

“You’re talking about the possibility of catastrophic outcomes for a whole school community,” said Levin, the national director of the K12 Security Information eXchange. “If there was somebody who was aggrieved and wanted to go onto the campus and create an issue, knowing that these files are out there, it certainly represents a heightened risk.”

Despite the significant volume, recency and sensitivity of the exposed files, community members said the district has failed to be transparent and forthcoming about key details. For a recent investigation, local television station WCCO News obtained district emails that exposed a nearly two-week delay between the time officials learned about the cyber attack and when they alerted families to what they euphemistically called an “encryption event,” warning them their personal data could be compromised.

‘I’m going to kill some kids’

Amid the national uptick in mass shootings, campus safety has become a top concern for parents, with nearly 70% saying they are at least somewhat worried about a shooting unfolding at their child’s school, according to a Pew Research Center poll.

Mass school shooters often conduct significant research and planning prior to their attacks, according to recent Secret Service research. Previous shooters have surveilled the campus police officer “in order to learn his route, noting security camera locations and trying to arrange meetings with a targeted teacher,” the report notes. Some rely on maps.

Prior to the attack on a Nashville Christian elementary school in March, police said the perpetrator conducted extensive surveillance of the school and drew a map that outlined their attack plan, which left three children and three adults dead. Just last month, a 20-year-old St. Olaf College student was arrested and accused of planning an attack on the campus roughly 40 miles south of Minneapolis. Police say the student had a gun magazine, plans to buy guns, a list of security radio frequencies and a map of the school’s recreation center with an exit route.

Breaking from a common procedure for data leaks, the stolen Minneapolis records weren’t published to the dark web. Instead, as The 74 first revealed, download links were published on a faux technology news site that’s indexed by standard search engines. They’re also available on Telegram, the encrypted instant messaging service that’s been used by terror groups and violent far-right extremists.

A single Telegram account was identified in a recent Vice News investigation as a primary source in a nationwide wave of so-called swatting calls. The swat-for-hire account holder has reportedly called in dozens of false mass shooting reports nationwide that have sent police scrambling to respond. Perpetrators tend to make the phony threats sound as credible as possible and access to school floor plans — perhaps on the same platform they already use — could be seen as extremely valuable. In recent posts on the app, the Telegram user identified by Vice announced that an online marketplace to sell their swatting services was set to drop in late May or early June, possibly leading to an escalation in the hoax attacks that are already bedeviling law enforcement.

The Minneapolis cyber attack isn’t the first time that hackers have breached a school’s physical security safeguards and exploited parents’ fears of mass shootings. In 2017, hackers with the notorious ransomware gang TheDarkOverlord infiltrated district computer networks in multiple states and used school data to send parents threatening text messages that invoked the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting. “I’m going to kill some kids at your son’s high school,” texts to Iowa parents read. In Montana, the hackers reportedly breached a district’s security cameras, allowing them to watch what was being recorded.

‘Complete damage control’

School safety experts told The 74 that Minneapolis officials must take immediate steps to mitigate risks after the hack. But the path forward, they said, won’t be easy.

Following a 2020 ransomware attack in Baltimore, the county school district reported nearly $10 million in recovery costs.

“The district, at this point, has to be in complete damage control mode,” school security consultant Kenneth Trump told The 74, adding that school leaders must adopt heightened situational awareness of potential threats moving forward and shore up their cybersecurity procedures to prevent additional leakage. “You can’t put the genie back in the bottle, it’s already out there. The first step is to take a look at your systems and what steps that you can take to prevent it from happening again.”

Yet the district should steer clear of reconfiguring its breached physical security systems “just for the sake of ‘haha, now you don’t know where they are,’” said Trump, president of the Cleveland-based National School Safety and Security Services. Such a move, he said, could simply make the campuses more vulnerable.

“If they were where they were supposed to be in the first place, they were there to serve a specific purpose,” he said. “It makes no sense: ‘OK, you know one (camera) is in the back hallway. We’ll show you — we’ll take it out.’”

Because camera systems and other physical security infrastructure is “essentially immutable,” the hack presents an ongoing concern, Levin noted, and could be exploited by threat actors well into the future.

State law requires public entities to “establish appropriate security safeguards for all records containing data on individuals.” To Gemberling, of the Minnesota Coalition on Government Information, it’s clear that didn’t happen.

“Somewhere along the way, somebody is going to sue about this because we live in a pretty litigious society,” said Gemberling, who regularly fields questions about the viability of lawsuits after data breaches. “I’m a retired attorney, I’ve written law review articles about this stuff. If somebody were to call me about this particular one I’d say, ‘Go for it.’”

While the breached sensitive information about individuals could open the district to litigation, he said the physical security records present an even greater risk should someone use the information to carry out an act of violence.

“Now you’ve got serious problems, especially if people could prove that, but for the failure to keep the data secure, that (attack) would never have happened,” he said. “That’s what security is all about, is keeping people from getting hurt.”

Sign-up for the School (in)Security newsletter.

Get the most critical news and information about students' rights, safety and well-being delivered straight to your inbox.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter