How Education Could Shape the Governor’s Race in California: Funding, Accountability, Charter Schools

Correction appended, updated Dec. 20

One lens into California’s sprawling size is its education system. Six million children under the age of 18 attend public schools — including 600,000 in charter schools — while nearly 3 million students are enrolled in the state’s storied higher education system, which is still struggling to recover from decades of underfunding. The largest teachers union has 325,000 members.

Although the contest to succeed Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown next November has only recently begun in earnest, early indications suggest education — along with issues like jobs, housing, and transportation — will be near the center of debate. With only 22 percent of state voters saying they approve of Donald Trump — and more than half saying Congress should refuse to work with him — the winner is likely to enjoy unusual influence in the state, and perhaps nationally, on education and other issues.

“I think this is going to be an important race,” said John Deasy, CEO of The Reset Foundation, a Bay Area juvenile justice reform organization, as well as a former Los Angeles schools superintendent. “My view is, the current regime in Washington has actually not pushed California further to the left, it has pushed it further into the national spotlight.

“I think we need a statesman,” he said of the gubernatorial race. “We need a proxy president.”

For the first time in years, the candidates will have an opportunity to offer big-picture education solutions that aren’t tied to a funding crisis. Brown, who is 79 and will term out next fall after one of the most successful political careers in state history, has presided over a series of spending improvements, including boosts to improve student equity and a localized funding formula.

More is needed: California continues to score poorly in an annual evaluation of school financing systems, ranking 39th among the states. Student academic performance in reading and math is also below most of the nation, according to the 2015 results on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. The Democrats in the race all call for greater funding, but their discussion at recent forums also focused on charter schools, teacher tenure, and accountability, according to press reports.

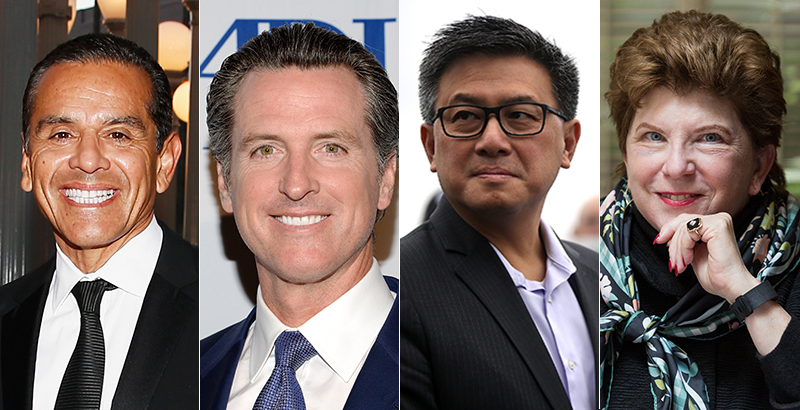

The early favorite is Gavin Newsom, 50, the talented, celebrity-backed lieutenant governor who served two terms as mayor of San Francisco, where he established himself as a star on the left with his early advocacy for same-sex marriage. Critically, in a state with several large media markets reaching 40 million residents, Newsom is a proven fundraiser who has banked $13 million so far, easily outdistancing the other contenders, and he has won the endorsement of the California Teachers Association, one of the most powerful and deep-pocketed unions in the country.

Newsom is running as the campaign’s progressive, which some find incongruous with his success as a businessman who founded and owns a constellation of restaurants and wineries. As a policymaker, despite CTA’s support, he has scant education credentials that appear more pragmatic than ideological. He supports community schools, a union job creator, but doesn’t reject charters.

Like the other candidates, he favors politically low-stakes proposals like expanded early education and reining in tuition costs for college students. He takes partial credit for California College Promise, a bill signed by Brown in October that aims to make the first year of community college free.

Early polls, which show about one-third of voters to be undecided, put Newsom’s support at 23 percent, followed by 18 percent for Antonio Villaraigosa, a former state legislative leader and two-term mayor of Los Angeles (as well as its first Latino mayor). Villaraigosa shares with Newsom more than a little dash, an eye for well-cut suits, and a gift for campaigning. He’ll run as a business-friendly moderate.

To Bruce Fuller, a University of California professor of education and public policy, the early self-sorting is ironic. “Newsom comes from well-heeled Marin County, while Villaraigosa actually comes from working-class Los Angeles and may be able to energize working-class Californians, regardless of ethnicity, hurt by Donald Trump’s attack on health care” and other policies, he said.

Unlike his younger rival, the East L.A.–born Villaraigosa, 64, is known for his education record and ardent support in the school reform community, which believes he pushed for charters and more accountability in the nation’s second-largest school district with little political upside and clear risks.

“It wasn’t necessarily politically expedient for him to do that,” said Ben Austin, past executive director of the Los Angeles reform group Parent Revolution. “I thought it was politically courageous and ultimately transformational.”

Villaraigosa also fought for teacher tenure reforms, backing the plaintiffs in the Vergara case, which challenged the constitutionality of state tenure and layoff statutes on the grounds that they harmed low-income students. The plaintiffs were ultimately defeated in court.

Like Richard Daley in Chicago and Michael Bloomberg in New York City, Villaraigosa also worked to win control over Los Angeles’s schools. He successfully convinced Sacramento to pass legislation giving him authority, but two courts found that the bill deprived Angelenos of their right to participate fully in the city’s schools. City residents elect a seven-member school board; the spring 2017 race was the most expensive in history, with charter supporters and teachers unions spending a total of nearly $17 million.

(The new politics of charter-union proxy campaigns was even more extreme in 2014, when the state superintendent race attracted $30 million, three times as much as the contest for governor. The loser, reform advocate Marshall Tuck, is running again in 2018.)

Villaraigosa left the mayor’s office in 2013 on something of a sour note, having earned the enmity of the school board — which would have become mostly obsolescent under mayoral control — and of the teachers union, while leaving some past backers believing he was more interested in self-promotion than governing.

“Fairly or unfairly, probably fairly in many ways, he was viewed as a show horse, not a workhorse,” said Larry Grisolano, a top adviser in both Obama presidential campaigns who has worked extensively in California.

Grisolano compared Villaraigosa to James Hahn, a career official in Los Angeles who was elected mayor in 2001. “It’s a classic case of people always wanting what they don’t have,” said Grisolano, who is not involved in the governor’s race. “Jim Hahn was quiet, not publicity-seeking, a workmanlike guy, a technician. The next election people wanted something kind of flashier and inspirational and a leadership type, and they got Antonio.”

Grisolano and other Democrats believe John Chiang, 55, the state treasurer and former controller, could be a dark horse. Currently polling at 9 percent — tied with John Cox, a San Diego–area businessman and the leading Republican, who is seen as having little chance — Chiang has raised $5.8 million, more than anyone except Newsom. He is little known outside the state but is liked by labor, particularly public employees, and, as the son of Taiwanese immigrants, he has appeal to the state’s large Asian communities.

Chiang’s education ideas have centered on better accountability for charters, more education funding and more flexibility at the local level to raise funds, early education, and free community college.

“One thing about California politics is that the controller’s office is extremely important, particularly to state employees,” said Grisolano. “He’s always been a stand-up guy for them.” Chiang became a folk hero to state workers while Arnold Schwarzenegger was governor, refusing to execute furlough and wage reduction orders that he considered illegal.

“I think he’ll kind of wear well with people. I think he’s thoughtful, he’s a decent person, he knows what he’s doing. He has kind of a politician’s touch without looking like a politician. I think he may be kind of underestimated at the moment,” said Grisolano.

Deasy agrees. “What strikes me is how different he is from the others,” he said, calling Chiang “powerful and compelling in lifestyle, leadership, leadership style, track record. I mean, he’s brilliant.”

Deasy’s remarks indirectly point to a big unknown in the race: what role, amid an extraordinary cultural shift in sexual mores, will extramarital affairs by Newsom and Villaraigosa play. In a race with relatively small differences between the candidates’ positions, personal attacks and character become more important; both of these seem to work in Chiang’s favor. (Chiang and his wife are divorcing.)

All of the candidates, irrespective of party, will run in a single primary in June, with the top two vote-getters — almost certainly Democrats — facing off in November. Given the similarity of Chiang’s and Newsom’s views on education, the campaign might turn to other issues should they finish at the top in the primary.

Another factor is age: Villaraigosa’s vigor notwithstanding, conversations about transitioning to a new economy and workforce will likely sound more authentic coming from Newsom.

A fourth Democratic candidate, Delaine Eastin, isn’t thought to have a real chance. But as a former two-term state superintendent, she may help keep education in the conversation.

Correction: Antonio Villaraigosa was Los Angeles’ first Latino mayor since 1872. Tom Bradley, who served from 1973-1993, was the city’s first non-white mayor. Information was corrected from an earlier version of this story.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)