How COVID, Technology Created Unruly Children

Kindergarten teachers, counselor say mischief is how students share their anxieties

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Effects of COVID-19 continue to be felt in classrooms throughout the community as veteran teachers deal with students who are more disruptive, destructive and disrespectful than in past years, and teachers attribute the lack of civility – at least in part – to the pandemic.

A district administrator and teachers union representatives said that this difficult behavior is going on throughout K-12, but for this story El Paso Matters focused on kindergarten, a foundational grade where students learn the basics from sounds, shapes, letters, colors and numbers, to counting, simple science, and how to function in a classroom to include respect for others and their space, and basic hygiene such as hand washing and covering coughs and sneezes.

This is an important issue for educators who must prepare these young minds with a proper base from which they will tackle future social and academic requirements to include state-mandated tests in third grade and beyond.

Leah Miller, owner of the Counseling Center of Expressive Arts in El Paso, said she regularly sees young clients who exhibit similar behavior and added that it often stems from anxiety, and misbehaving is how they cope and communicate.

“A lot of times when kids have anxiety, they act out in ways that we don’t typically understand because they can’t articulate to us that they’re anxious,” said Miller, a licensed professional counselor who specializes in play therapy. “That’s when you see impulsive behavior.”

Kindergarten teachers and staffers from area districts shared similar stories of students who are unprepared for a structured learning environment and unwilling to conform despite the teachers’ best efforts. Congratulatory stickers, positive reinforcement and meetings with parents, counselors and campus administrators have not affected most of these children who continue to act up well into the spring semester.

The teachers, who did not want to be identified for fear of retaliation, said they noticed early in the fall 2022 semester that more students than usual were having a hard time adjusting to school. A teacher education leader at the University of Texas at El Paso said that she was aware of the issue and suggested to one district a way to help, but her offer was rebuffed.

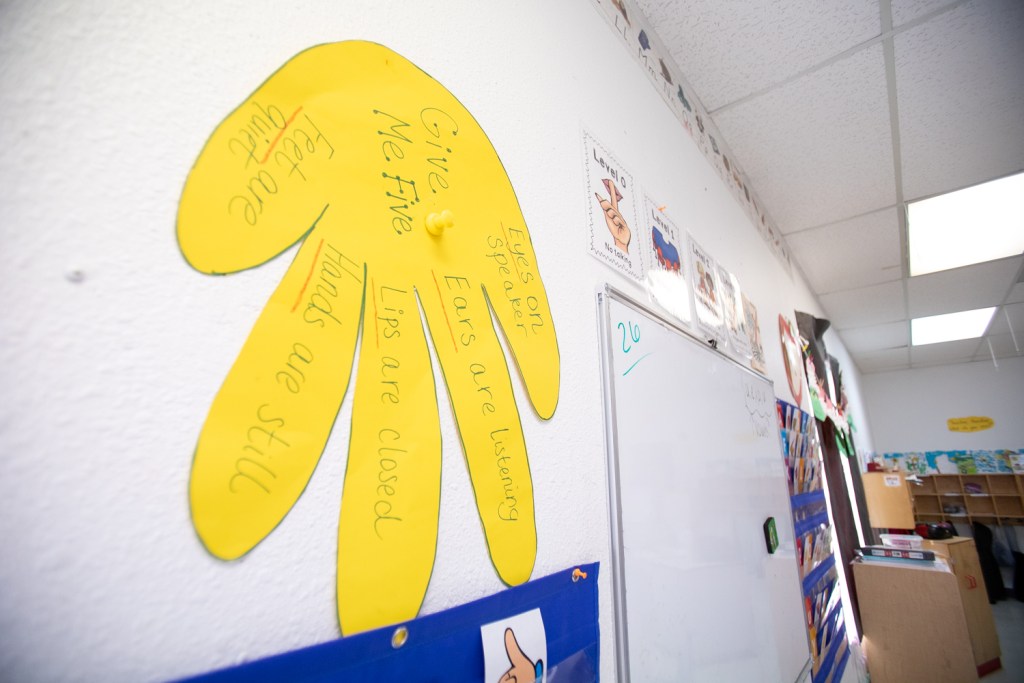

Instructors described students – mostly 5-year-olds – who cursed, overturned chairs, disrespected others and their property, and delighted in ripping down learning charts and decorations in the classroom and along the hallways. They also depicted others who exhibited moodiness and such dangerous tendencies as biting, using scissors to cut the clothes of other students, and running out of their classrooms or cafeterias and into the campus parking lots.

The frustrated teachers acknowledged that they have used every tool in their instructional arsenal, but have made little to no headway in many cases. They lamented a lack of support from campus leaders, who ask teachers to be more understanding of the youngsters, and parents, who do not deliver on promises to change a child’s behavior or deny their child has a problem in the first place.

“Sarah,” a teacher for more than 10 years, said she had previously experienced an occasional student with anger issues, but was surprised to find three disruptive students in her class for the fall 2022 semester. By February, that number had grown to seven, almost a third of her students.

“I’m constantly putting out fires,” she said figuratively. “It’s very draining. The whole situation just makes me sad.”

While some teachers said this year’s circumstances have made them consider changing the grade level they teach, the campus or their professions, others talked about going home after a tough day and researching other ways they might be able to connect with their students “who need extra love.”

The teachers did not want to say how many student referrals (reprimands) they had written this year. Each referral involves a lot of documentation of who did what and when. At that grade level, the consequences for referrals range from lunchtime detention, loss of privileges such as participation in a class party, and in-school suspension.

One teacher suggested that districts needed to do more to address student mental health like hiring behavioral therapists on every campus.

Miller, the professional counselor, said that it is possible that the parent/caregiver gave the child technology during COVID isolation because the adult needed to work, and they wanted to keep the child quiet. She said the abundance of screentime meant that children did not have enough time for unstructured play, where they learn social behavior and how to solve problems. Some examples of unstructured play are artistic or musical games, construction of clubhouses with boxes and blankets, and the exploration of the kitchen cupboards.

In “Screen Time and the COVID-19 Pandemic,” an article in the March 2023 edition of PlayTherapy Magazine, Sara Loftin, a licensed professional counselor, echoed much of Miller’s theory in regard to adults using technology as a babysitter. The article, which cited numerous studies, pointed out that long periods of screen time will negatively affect a young child’s development of language and social skills as well as their abilities to solve problems, think creatively, or learn to deal with their boredom. The article goes on to state that as screen time often is an individual activity, the child user does not learn about impulse control or empathy in social settings.

While it is late in the academic year, Miller said it was important for teachers to build relationships with their students. It is her experience that good relationships deter poor behavior. She also suggested two ways the teachers could work with the students with issues. They included situations where the teacher will acknowledge the students’ feelings, communicate the limit to the bad behavior, and then offer an acceptable alternative. There also is a 30-second burst of attention where the teacher focuses on the child for 30 seconds and then tells the student that he/she needs to get back to work.

“Maria,” another established teacher, lamented her students’ lack of relationship skills. She said one of the main differences between her current and past classes is that this group likes to bicker with no interest in resolutions. She has 20 students in her class and about half have “issues.”

“I can’t teach,” she said. “I just try to manage their behavior.”

Maria has called numerous parent meetings, but each parent seems dismissive of the problem. In one case, a student began to tear down educational materials from a classroom wall and the mother just watched passively.

Maria said she has asked her school’s counselor and administrators for help, but they are always busy.

El Paso Matters reached out to representatives from the region’s big four school districts regarding this issue, but the only response came from Diana Mooy, Ysleta Independent School District director of the Department of Student Services.

Mooy, a former teacher and school administrator, said that the concerns raised are common among kindergarten and first-grade teachers, and that YISD was aware of the concern. She said her district trains teachers to learn what in-school or out-of-school factors trigger the negative behavior. The district director reasoned that COVID-19 eliminated many opportunities for this generation of kindergarten students to socialize with peers on play dates, or learn how to behave outside the home.

She said the district provides its teachers – and parents – with various support programs, and social emotional learning curriculum and discipline management techniques to help the child before things escalate. She added that YISD’s K-12 teachers are supposed to set aside 30 minutes per week to talk with students about self-regulation and relationship building to give them the necessary tools to manage their emotions in a healthy way.

Mooy said that district kindergarten teachers had submitted about 200 referrals as of February, which is a number consistent with past years. The district registered 2,309 kindergarten students during the 2022-23 academic year.

She encouraged any teacher in her district to contact her to discuss strategies and interventions, and added that she would be willing to talk with campus administrators to get the teachers the support they need.

Norma de la Rosa, president of the El Paso Teachers Association, was among the union representatives who acknowledged that they had received more calls this academic year from teachers who requested guidance on how to handle students who are more unruly than usual. They tell the teachers to follow their districts’ protocols and to document incidents as much as possible. In worst-case scenarios, she tells teachers to file a Chapter 37 of the Texas Education Code that allows them to remove disruptive students from their classrooms.

“I tell them to do what they need to do,” de la Rosa said. “You’re not to be a punching bag.”

The union leader knows that campus administrators do not want teachers to file charges against students, but they should be ready to go up the chain of command if necessary to the district and the Texas Education Agency. She said the district’s attitude is that if a teacher needs to write a referral, they should write the referral.

“Right now the kids know there are no consequences,” de la Rosa said. “The districts need to change that mentality.”

Teachers want parents to take a more active role in eliminating their children’s misbehavior, as opposed to a concept that they hear more than they would like, the children are the schools’ problem from the day’s first bell to the last.

“Savannah,” a parent who works in the schools, said she noticed misbehavior in her child’s class but was not as concerned because the class had a veteran teacher, and her son continued to do well academically. Early in the school year, campus leaders assigned a teacher’s aide to the classroom and brought in one of the district’s behavioral therapists to work with the disruptive students, who eventually were separated into different homerooms. One of the students left the school.

“I thought (the teacher) was as effective as she could be,” said Savannah, who added that the teacher assured her recently that the rest of the class had caught up to where it should be academically. “I’m happy to know at this point of the year that all things are straightened out and that the class is in a better place than where it was at the beginning of the year.”

Alyse C. Hachey, co-chair of UTEP’s Department of Teacher Education, said last September that the college offered the services of its award-winning early childhood education faculty expert to provide special professional development to all El Paso Independent School District teachers and administrators who served pre-K and kindergarten students.

“The district refused to have administrators trained and so turned down help from UTEP faculty,” Hachey wrote in an email. “We stand willing to help. The districts’ need to let us.”

In a February email, Hachey said she had not pursued the matter.

Sarah said one possible solution would be for the state to put less focus on academics at that level and focus more on social emotional learning.

“At their age, it’s not hard to be overstimulated,” Sarah said. “We need to teach them how to share and play together.”

This article first appeared on El Paso Matters and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)