How Can We Learn When Our Earth is Burning?

Extreme Weather, Virtual School and Racial Justice Movement Fuel Renewed Push for Climate Education

By Marianna McMurdock | August 3, 2021Updated, August 9

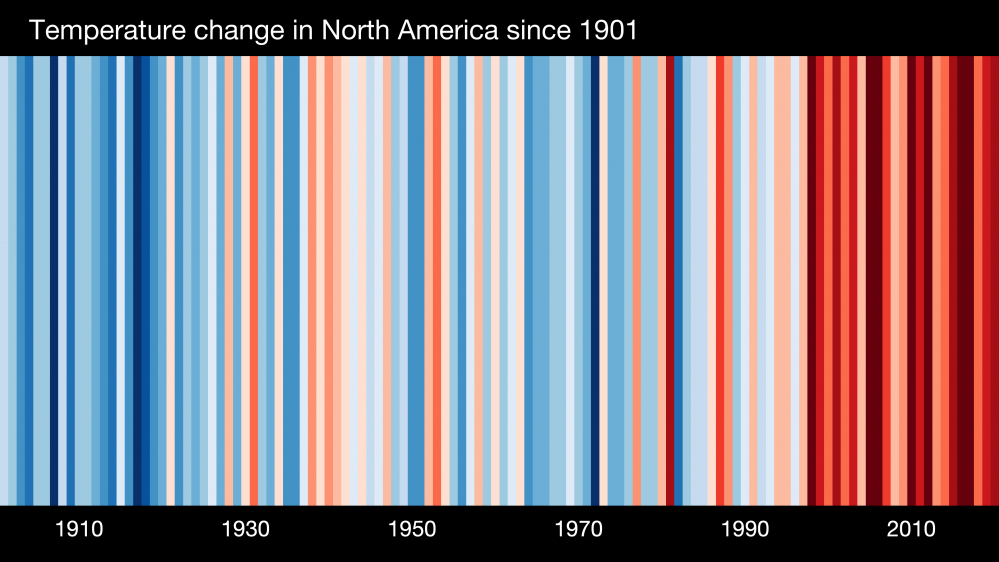

This July, air quality worsened from Oregon to Maine as wildfire smoke traveled across northern states. New Yorkers woke up to an orange sun, and Utah’s worst drought turned deadly as a sand storm blocked visibility on a major highway. And while reports of extreme weather and restrictions on teaching dominate the news, young people are renewing the push to make climate education a reality in K-12 schools.

After learning that her state bird may have to leave if Minnesota continues to warm at its current rate, and connecting extreme weather at home to a global phenomenon, high school senior Annie Chen started a campaign to get more climate-oriented books in Minnesota schools. She recalls having to wear her winter coat over Halloween costumes as a kid, but recently, the snow hasn’t reached her home in Rochester until later in the season. Hotter summers seem to linger through September.

“I think that younger people are definitely worried a lot,” she says. “The students who are worried and trying to get [climate education] into schools are doing so because they were just curious like myself and went out there to learn on their own — and then realized the importance of this education.”

Chen’s activism reflects a national push for comprehensive climate education that educators, scientists, students and advocates say is gaining strength this summer. The movement is something of a perfect storm resulting from expanded access to virtual climate education resources created by the pandemic, the increasingly visible and dire reminders of the global climate crisis, the weakening presence of climate deniers and a growing awareness of the connections between racial and climate justice.

In partnership with other Minnesota youth and the national advocacy group Climate Generation, Chen is working to advance a state bill that could make climate justice education required. Her home state is one of 24 across the country that developed their own version of the Next Generation Science Standards / Framework for K-12 Science Education.

Widely adopted since 2013 in 20 states and Washington, D.C., the Next Generation standards include climate and weather. For high school, students are expected to understand how changes in energy flow affect Earth’s climate, and be able to assess climate change’s future impacts to the planet’s systems.

Some states adopted much of the framework, but omitted mentions of manmade climate change, leaving students like Chen to potentially graduate without understanding the larger system of greenhouse gases, carbon emissions and global warming unless their teachers incorporated it into their lessons voluntarily.

On August 9, a United Nations report of over 3,000 pages created by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change detailed how that larger system is warming the Earth and creating “unprecedented” changes. In every scenario, scientists predict the world will cross the threshold of a 2.7-degree increase in temperature, set in the 2015 Paris climate accord, sometime in the 2030s. United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called the report “a code red for humanity,” stating world leaders need to urgently address the crisis and curb emissions if they’re to prevent subsequent, compounding emergencies worldwide.

“Teachers are sort of like trying to cloud us from the truth. They’re introducing it like it’s a baby threat — like it’s not gonna potentially wipe us all out, and Earth as we know it if we don’t do something.” Enzo Nicolai, New York City 5th-grader

Given the gravity of the subject, younger generations are experiencing climate anxiety. For one elementary schooler, that’s no reason to slow the spread of climate education, especially when lessons pair solutions and actions alongside science. He needs the inclusion to be “more urgent.”

“I just respect the fact that, well, the earth has given us so much and we’re treating it like a giant pile of garbage,” rising New York City 5th-grader Enzo Nicolai said. “Teachers are sort of like trying to cloud us from the truth. They’re introducing it like it’s a baby threat — like it’s not gonna potentially wipe us all out, and Earth as we know it if we don’t do something.”

The politics of teaching climate change

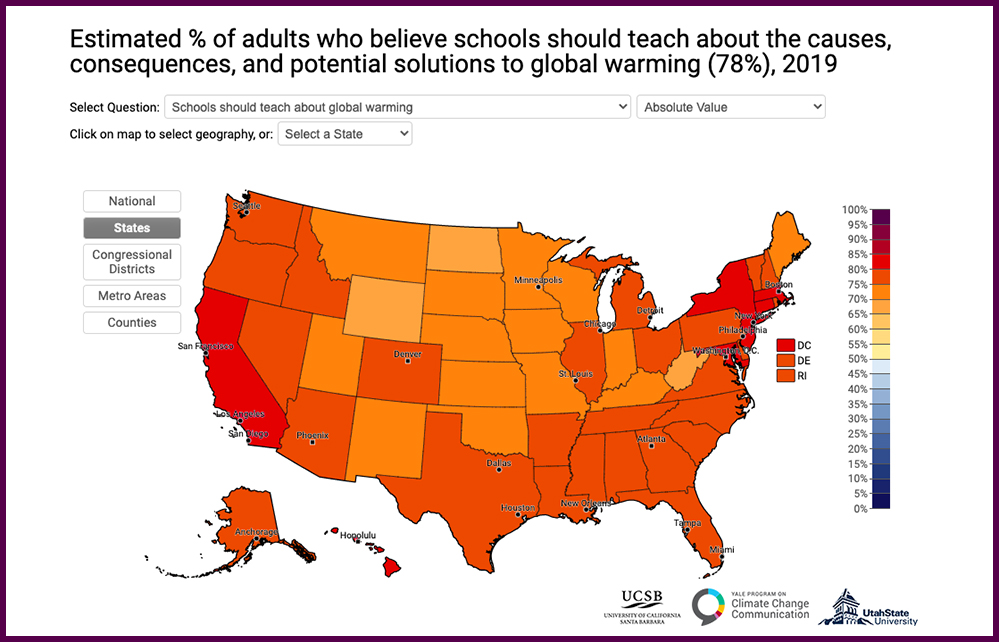

According to Yale’s 2020 Climate Opinion Map, roughly 72 percent of American adults believe global warming is happening. And according to its 2019 iteration, an estimated 78 percent believe schools should teach about “the causes, consequences, and potential solutions to global warming.”

Similarly, an NPR/Ipsos study found that more than 80 percent of parents wanted their childrens’ schools to teach about climate change. Still, with a majority of the public interested, consistent climate education in K-12 classrooms does not yet exist.

Yale lecturer and researcher Jennifer Marlon has studied climate and wildfires for years, examining sediments and producing the opinion maps to help show how folks across the country perceive climate change.

In 2015, only 10 percent of the nation’s adult population were ‘dismissive’ of global warming, believing climate change is not a threat or not caused by humans. Five years later, only 8 percent are classified as “dismissive,” while 55 percent are “concerned” or “alarmed” by the global threat.

“There’s a widespread misunderstanding that a lot of people still don’t really care, or aren’t taking it that seriously, and the reality is more than half care tremendously and are taking it very seriously,’ she said. “But there’s a widespread gap in the fear and the anxiety versus the knowing what to do about it.”

For Marlon, the social dynamics of climate change are deserving of more attention. Many don’t yet know how to have critical conversations about warming and carbon emissions to engage their peers “in the steps they need to take to make their communities safe, their homes safe, and their neighborhoods safe, without worsening the political divisions.”

Students and teachers are seeing those very political divisions play out with a movement to prevent lessons on systemic racism from entering the classroom, a conflict that’s come to be known as critical race theory. Efforts to learn and engage in climate change solutions may be thwarted in Texas and other states where teaching restrictions go beyond racialized content, curtailing classroom activity that enters the realm of political advocacy.

For students in Texas, letter-writing campaigns or service learning with climate policy organizations may be activities of the past because of the legislation.

“When you shut off the flow of information to people, they can’t make decisions well,” Marlon said.

With states taking different approaches to climate education standards, and because most teachers did not encounter climate change in their own schooling, many have turned to education and advocacy organizations like Climate Generation, Alliance for Climate Education, and the CLEO Institute for resources.

These groups have built partnerships with districts — CLEO’s, most notably, with Miami-Dade schools — and have seen interest from teachers and students grow steadily in recent years. Climate Generation’s network of teachers is now at about 8,000 nationally; the organization has offered professional development and curricular resources for educators since 2006.

Its Education Manager Lindsey Kirkland has witnessed some state policy support crop up, beginning to match student- and teacher-led interest in making climate education more widespread. New Jersey, for example, recently adopted climate change standards that span content areas — not limited to science.

Kirkland believes the uptick in policy support and increasingly apparent intersections between systemic racism and climate change are pushing educators and youth to seek out climate education resources at this moment.

“I think folks are looking for resources on justice and oftentimes a great way to bring justice into a science classroom is through climate justice programming,” she said.

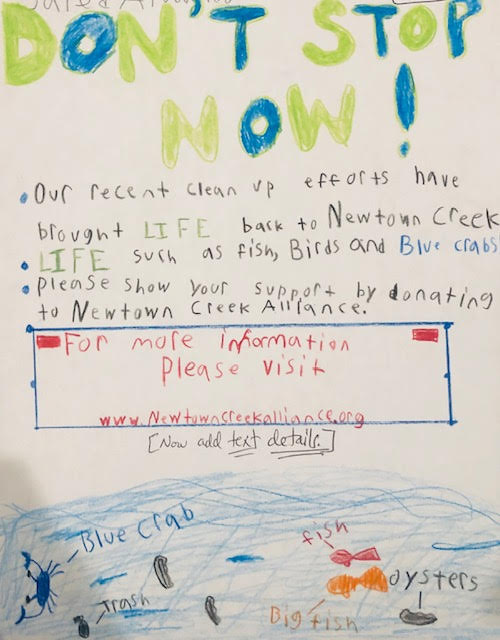

Jonathan Schulman, a 4th-grade teacher at PS 110 – The Monitor School in New York, is one educator who has taken on a justice-centered approach to his climate lessons. Since recent spotlights on racial inequity, he’s noticed “there’s a push” among his colleagues to incorporate climate and racial justice across content areas and in more localized ways.

In recent years, some of his classes have learned about the East River, Newtown Creek, and Gowanus Canal — polluted waterways that surround their Brooklyn school. They also discuss why storms seem to hit more vulnerable communities; from New York to Delaware and Louisiana, flood-prone neighborhoods are predominantly low- and middle-class as a result of economic segregation.

Federal redlining policies in housing created inequities in land distribution; today, lower-income communities of color are concentrated in hotter neighborhoods, with few trees and an abundance of pavement.

“Before I was thinking, just stop our carbon footprint, reduce it — you’re thinking well that’s great, we can do that, we can save energy, but how can we really help people that need it the most?” Schulman said. “We are finding ways that we can become allies in the Black community and part of that is climate change.”

The shift to explore climate justice, not only climate science, is growing among California educators as well. Currently the largest, most active subgroups within the California Association of Science Educators are the equity and environmental literacy committees, according to the group’s president and former high school science teacher Peter A’Hearn.

“I think there’s a real push on all of those fronts, right at the intersection of the idea that climate change affects low-income and communities of color a lot worse than it affects wealthy white people,” A’Hearn said. “What are the impacts of and what are the communities where we put toxic industries?”

It’s fun in the worst way

Teacher interest comes at a time when reports of pandemic learning loss and parent concerns about politically charged curricula are growing. In conservative-leaning Utah for instance, Teacher of the Year John Arthur hasn’t noticed his fellow educators any more eager than usual to leap into climate change-specific curricula in the fall, even with historic weather affecting the state.

“There are a lot of debates right now throughout the country about what teachers should or should not be teaching in their classroom, what is and is not within our purview, whether it’s critical race theory or manmade climate change. A lot of teachers have found that they need to walk a fine line,” he said.

Arthur explores pressure systems, observable weather changes, and the greenhouse effect with his 6th-grade students at Meadowlark Elementary, a Salt Lake City school that serves predominantly low-income families. Often that means incorporating news and current events to help students observe and investigate the changing climate around them.

“It’s fun, in the worst way because it’s exciting, it’s engaging, but we’re learning about the devastation of our planet, and thinking about the impacts that’s going to have on my students, their generation and the generations to come.”

For rising Monitor School 5th-grader Kristina Morgan, opportunities to work on or write about climate change next school year can’t come fast enough. She fondly remembers writing a paper on how to slow soil pollution.

“I enjoy learning about the environment,” she said. “I think that some kids in third grade — not only like the higher grades — they should learn about it.”

Her peer Nina Solis also liked the climate-specific lessons and learning that she could control or stop some aspects, like water pollution, with her actions.

“If children learn about this, when they grow up, they’re still gonna carry that knowledge. They could tell it to their children, anybody that they could reach out to — they could tell it to them and then we all could help save the earth, one by one.”

More confident, less anxious about the future

Excitement for expanding climate education doesn’t only stem from student activists or students familiar with the subject. Experts and professors in the field of climate science are noticing a bubbling effect from youth completely unfamiliar with the foundations of their work.

Jen Pierce, a Boise State geoscience professor who helps bring climate education to K-12 students in Idaho, teaches an introductory climate science course. This fall, high school students will enroll with the financial support of Jane Fonda, the 83-year-old actor and activist who was arrested in 2019 for protesting climate change in Washington, D.C.

“I have seen interest and advocacy coming from younger students and young people in general, around creating a climate future that they are comfortable with, and that will protect ecosystems and human life,” said Kimberly Miner, earth scientist with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a leader in climate science. In years past, Miner would go months at a time without outside inquiry, yet recently has seen weekly requests from professionals, students and educators seeking to understand more about climate change.

The lab’s K-12 education division saw an influx of demand for climate and earth science materials as the pandemic began, with parents and educators seeking new methods to teach online. Annually, they choose a different STEM theme to center lessons and resources around. For the first time in years — given the wealth of engineering, space and chemical science data they create — they decided to repeat a theme: climate and earth science for 2021-22.

After an isolating pandemic school year, advocates and leaders encourage teachers to lean into interest in climate education as an opportunity to encourage student participation.

“Picking things that are relevant to them — like fires and climate change, they all see what’s happening in the world and they have concerns — that’s a relevant hook that helps bring kids back and get them re-engaged,” A’Hearn says.

Particularly given a growing student mental health crisis and heightened levels of anxiety, students urge educators to provide climate solutions alongside any science, social studies, or humanities curricula that makes its way into the classroom.

“Something that’s important to me with learning about climate justice is like learning about the solutions to it too. It can be kind of overwhelming, just learning about all the issues, but there are plenty of groups out there who are working on solutions — there’s many bills and deals and things that students can work on,” said Maya Hidalgo, who’s entering 12th grade at her Minneapolis high school.

Hidalgo and her peers organized an environmental racism book club and presented climate education resources to Thomas Jefferson High School’s science department in the hopes some topics will make their way into classrooms this fall.

Outside of the classroom, she’s been involved in the Minnesota climate justice education bill — the same one Annie Chen looks to build steam behind. Should it become law, students would participate in required, schoolwide climate justice projects.

“The ability to advocate for yourself and your community helps to address mental health concerns. The benefits are not just the students learning, although that’s also very important. What we see is that students are more confident and less anxious because they see these issues and they’re not told, wait until you’re older, vote for this,” Karolyn Burns, science educator and program manager with the Florida-based CLEO Institute, said.

In much of Oregon, where record-breaking temperatures reached 117 last month and devastating wildfires continue to burn, orienting K-12 students toward climate education and solutions have become a way of life as they cope with extreme weather challenges. The state adopted the Next Generation Science Standards in full, so all K-12 students encounter some weather and climate education. The Eugene Water and Electric Board also funds a teacher on assignment for climate, energy, and conservation: Tana Shephard.

Now in her 20th year as an educator, Shephard works across content areas to help social studies, humanities, and science teachers incorporate lessons on earth science, renewable energy, and individual “carbon stories” — storytelling about students’ and teachers’ lived experiences with climate change.

Known in Eugene as the electric car woman vocal about climate justice, Shepherd shares that more people in the last year have been taking her up on critical conversations, including custodians, nutritional staff, and principals. Even in Oregon where climate activism from students and teachers is consistent, she’s noticing a “cultural shift” as a result of increased news coverage, student desire, and the growing climate justice movement.

“Although we’re in a dire situation with fire and all kinds of different [weather],” she said, “it’s sort of like the stars are aligning.”

Lead Image: Residential flooding (left), a sand storm in Death Valley (center, Hugh Peterswald/Pacific Press via Getty Images), and smoke haze over Manhattan (right, Wang Ying/Xinhua via Getty Images)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter