How Arkansas Is Teaming Up With Teachers, Facebook & Other Tech Titans to Rethink Computer Science Education

During third period in a North Little Rock classroom, Arkansas Gov. Asa Hutchinson and a group of high school students fixed their eyes on their computers, trying to make a colorful cartoon bird fly across the screen.

Hutchinson, a slender, white-haired man, smiled through his frustration as he struggled with Scratch, a programming language developed by MIT graduates for coding beginners, to get the bird moving in the right direction. In the front of the room was tall, lanky Justin Cobb, a computer science teacher who likened the exercise to plotting numbers on a number line.

“Do you remember which way is the positive X direction?” Cobb asked.

“To the right,” Hutchinson responded.

Hutchinson, as captured on local TV, was experiencing firsthand what students across his state are learning, thanks to an ambitious, first-in-the-nation initiative he is spearheading — in partnership with universities, major corporations, and educators— to teach computer science to every student in Arkansas.

Known more for low salaries and poor test scores than for a bustling technology sector, Arkansas is going all in on computer education, spending an initial $5 million to train teachers and help districts pay for staffing and equipment to bring computer literacy to all grade levels. Arkansas educators, business leaders, and policymakers are working at warp speed to fill a void in the computer education world by creating road maps for bringing computer science to elementary and middle school classrooms. They have literally written the book on how to teach computer literacy to children as young as 5. They have developed virtual classes for rural, low-income, and minority students whose schools can’t afford in-person instruction — piggybacking on pre-existing internet connections so they’re not left out.

In the two years since the initiative launched, the number of Arkansas high schoolers taking computer science has exploded, from 1,100 to 5,500 students — nearly 20 percent of the high school senior population.

Hutchinson’s ambitious but unproven agenda has stoked both optimism and skepticism among researchers about the potential benefits that technology and computer science education can have in a state where the majority of third-graders are not competent readers.

University of Arkansas education professor Gary Ritter said the initiative might ramp up student engagement, which could lead to better classroom performance in other areas. Robert Pondiscio, a senior fellow at The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, cautioned that emphasizing computer science could distract educators from more fundamental priorities.

“I’m not anti-technology, but I will always be a little suspicious of the shiny new thing,” he said. “The first and best test of any state’s … education system is basic literacy. It is the skill of skills.”

Still, Arkansas’s program is attracting nationwide attention — the majority of it positive — and technology giants have been funneling resources into the initiative.

In January, Arkansas became the first state to participate in Facebook’s virtual reality program, which the company expanded in August to include computers, digital cameras, virtually reality viewers, and other technology for every high school in the state. And late last year, Microsoft signed on to help the state promote computer science education, agreeing to host a DigiCamp to further expose young people to the technology field, as well as offer training to local entrepreneurs.

Together, the two companies have provided more than $1 million worth of technological equipment, promotional events, and training.

“Governor Hutchinson has been undoubtedly a leader when it comes to computer science and making computer science count here in the state of Arkansas,” Fred Humphries, Microsoft’s vice president of U.S. government affairs, said in announcing the partnership.

And as other states work to bolster computer literacy in their own schools under the new Every Student Succeeds Act, they are looking to Arkansas — ranked 39th in education on the most recent U.S. News and World Report list — for inspiration.

“Arkansas helped launch what is easily a wave of states that have made computer science policies a priority in the last few years,” said Cameron Wilson, chief operating officer and vice president of government relations of Code.org, a nonprofit that promotes computer science education. “I’d say Arkansas has the most detailed set of policies that we have seen.”

New law, new push

Business leaders and supporters of computer science education have long argued that improving the technical skills of Arkansas’s workforce is a necessity in state where the median household income is below $45,000 a year and the largest employers are Walmart, Tyson Foods — the world’s largest poultry producer — and Union Pacific Railroad.

For more than a decade, a coalition called Accelerate Arkansas lobbied governors to expand the state’s economic base by encouraging technology-based businesses and producing an educated workforce to staff them — but got nowhere.

“We were trying to accomplish getting more kids interested in STEM,” said James Hendren, one of the founders of Accelerate Arkansas. “We’ve got … a lot of very large companies and a big startup community that needs these kind of workers.”

Then Hutchinson came along. In 2014, he was running for governor, and the story goes that he was inspired by his granddaughter, Ella Beth, who had taken a computer coding class online.

“I said, if my granddaughter, 11 years old, can have that much fun and be that successful in [computer science], we ought to have that in every high school in Arkansas,” he told The 74.

At the time, only 18 of the state’s 260 districts offered computer science; of the 1,100 students who took the classes during the 2014–15 school year, 80 percent were boys.

Ella Beth made a downloadable app for the campaign, and she and her coding prowess were featured in a commercial. In it, Hutchinson vows to provide computer science classes, especially coding, in every Arkansas high school as a path to high-paying jobs for both boys and girls.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUPfQ5bDdTQ

Thanks in part to that soft campaign promise, Hutchinson won the election. But he and his supporters had a larger goal in mind. Coding wasn’t just a school elective — it was a tool for competing with technology hubs such as Silicon Valley and Austin, Texas, for companies looking to relocate.

Soon after, the legislature passed a law requiring every traditional public and charter high school to offer computer science by the 2015–16 school year.

But Arkansas didn’t just need a mandate for high schools; it needed a cohesive vision for what computer science education would look like in every grade, and a pipeline for educators to teach it. In April 2015, the new governor tapped Anthony Owen — a former math teacher who had risen through the ranks and was already spearheading the state’s computer science education program — to be director of computer science, in charge of designing and implementing that plan.

Owen is a former college dropout, raised by a single mom on a cattle and poultry farm in Star City, Arkansas, who knows firsthand the advantages that a background in technology can provide. He spent several years working in stores like RadioShack before returning to college, learning math and computer science, and becoming a high school math teacher in the Arkadelphia Public Schools. He went on to become a math specialist at the Arkansas Department of Education and began informally taking on extra work to bolster computer science in the state.

Meanwhile, the state set up a task force of educators, administrators, and tech industry representatives to design new K-12 standards for computer science, with specific learning goals for every grade level. Or, in Owen’s words, “make computer science a normal part of every day.”

The task force focused first on designing the elementary and middle school standards, which would be harder than creating standards for older students because they are a newer, less established area of education. Arkansas was able to draw on sample elementary and middle school standards designed by the Computer Science Teachers Association, but creating expectations for every grade level in elementary and middle school, instead of clusters of grades, was something entirely new.

Some of it merely involves teaching simplified versions of more advanced skills. For instance, the standards call for fifth-graders to “demonstrate basic steps of algorithmic problem solving.” But since an algorithm is just an equation unfolding in a particular sequence, the standards say the concept can be illustrated by the everyday process of making a peanut butter and jelly sandwich.

Fifth-graders might not be able to learn the programming language C++, but they can master the concept of a loop — a repeating sequence of commands designed to achieve a specific result.

For younger students, there are games and tools that simulate programming. KIBO, a robotics kit, lets kids use blocks to command a robot to perform different functions. MIT and Tufts researchers created ScratchJr., a version of the programming language Hutchinson was experimenting with, simplified for a younger audience.

Or, as Owen explained, “you have a math teacher teaching subtraction and she talks about little Susie holding 16 balloons and she lets four go. Why not talk about little Susie has a 16-gigabyte iPad and there [are] 12 gigabytes taken on it. How many does she have left?”

“It’s something more relevant to little Susie’s generation today, but then you can have that conversation about what is a gigabyte.”

The K-8 computer science standards, which were adopted in January 2016, are expected to be implemented in every elementary and middle school in the 2017–18 school year, whether in separate computer science classes or incorporated into the normal curriculum.

“You are really teaching logic. You are teaching a way of thinking,” said Nathan White, director of services for the Star City School District.

For the high schools, the standards build on content kids learn in the younger grades and conform to generally accepted standards for what high school computer classes should look like. Schools can offer one of several courses, including computer science with a programming emphasis, mobile application development, computer science with a networking emphasis, robotics, computer science with information security emphasis, or Advanced Placement computer science principles.

By the 2015–16 school year, every high school in Arkansas was offering at least one computer science class, and many had more than one.

The North Little Rock example

For the North Little Rock School district, the new standards meant refining its approach to K-12 computer science education.

The 9,000-student district had sought a state grant in 2014 to offer computer science in its high school in partnership with Project Lead the Way, a nonprofit providing online STEM curricula and training to districts across the country. Following the state’s new guidelines, North Little Rock educators began teaching computer science using the nonprofit’s digital content in 2015.

At the same time, its nine elementary schools and middle school began incorporating more computer science into their keyboarding classes, said Deputy Superintendent Beth Stewart.

A new Center of Excellence at North Little Rock High School, designed, in part, by local technology and manufacturing companies in need of workers, will offer majors in transportation distribution and logistics, advanced manufacturing, computer science, engineering, and health care. Computer science content will be incorporated throughout all the courses.

Other districts are considering starting similar academies at their high schools.

“It was so essential to have that computer science piece in the center,” Stewart said. “You can’t work now without some basic computer science.”

Initially, “We thought maybe we would have 300 to 400 [interested students], but we’re pushing 500 right now,” she said. “We are enrolling people every single day.”

Training the next generation of teachers

By far, the biggest problem facing Arkansas’s computer science education plan was finding enough qualified educators. Computer scientists often have better-paying options outside teaching, and public school teachers don’t typically have computer science knowledge or certification.

The state tackled the teacher pipeline problem in two main ways: rapidly creating professional development programs to train teachers in computer science education, and working with online education provider Virtual Arkansas to offer free digital computer science classes for high schools that couldn’t provide in-person instruction.

The state earmarked nearly $1 million for 15 teacher training programs during spring and summer 2016, focusing on the new K-8 standards, coding for elementary and middle school students, and the content needed to teach entry-level high school computer science and become certified.

By the end of the latest school year, some 2,000 teachers had participated. Local universities are working to help train the aspiring computer science teachers, with Harding University, for example, providing summer instruction and follow-up sessions during the school year. Recently, Arkansas Tech became the first college in the state to offer a computer science education major, which blends existing computer science courses with education classes.

For high schools that can’t afford a computer science teacher, Virtual Arkansas offers a menu of online courses approved by the state. In the popular “computer science essentials” class, students learn the history of computers, how they work, and a variety of programming languages. They create a website about a topic they are passionate about using HTML code, format it using CSS, and add animation using Javascript.

Rural schools can access Virtual Arkansas using equipment installed by the state to fill technology gaps when it started administering the computerized Partnership for Assessment of Readiness for College and Careers standardized test, Owen said.

“We were the only state that I’m aware of that was successfully able to test over 95 percent of our schools online with the PARCC online assessment system in the first year it rolled out,” Owens told The 74. “Even though there are unique needs [for] the rural areas, we had a lot of infrastructure already in place and a lot of consideration to technology needs because of the PARCC assessments.”

During the 2015–16 school year, 1,238 students at 175 schools took Virtual Arkansas computer classes. The following year, 209 schools offered the course but only 908 students participated.

Leveraging student involvement

For all this focus and preparation, though, the high school computer science classes are electives — students have to be persuaded to sign on. So the Education Department partnered with an ABC-TV affiliate to produce an advertisement that was shown in 22 movie theaters around the state. Hutchinson also went on a marketing blitz, giving interviews about the importance of computer science and hosting assemblies at schools statewide.

But the best promotional tool might be K-8 teachers themselves, particularly for girls and minority students.

When it comes to computer science enrollment, “We are actually close to 30 percent female and little over 70 percent male, which is better than national but still horrible,” Owen said, adding later that there is a much smaller racial disparity. “We think by taking action to try and close that gender gap, that the racial discrepancies of underserved populations will automatically try to correct itself to a certain extent.”

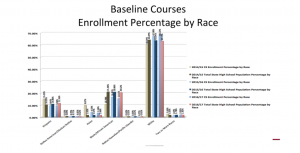

During the 2016–17 school year, African Americans made up 20 percent of the state’s high school population but just 15 percent of computer science students. Comparable numbers are 12 percent and 10 percent for Hispanic students, and 63 percent versus 68 percent for whites.

Targeting computer science at younger grades might help address some of those disparities, because studies show that kids absorb stereotypes about race and gender at an early age. A study this year found that girls are less likely to believe their own gender is brilliant by age 6. Other research suggests that when children are exposed to STEM education at a younger age, they are less likely to embrace gender-based stereotypes about technical careers and more likely to enter those fields later in life.

“If you look at the statistics [about] K-8 teachers, they are predominantly female and they are more representative of the communities,” Owen said. “What our vision is with those K-8 standards is that you will have a generation of students going through seeing their heroes, seeing Ms. Johnson, who looks like them [and] who is a female talking about computer science standards. [She is] not afraid of it showing that it is for women, it is for minorities, and that makes it OK for them also.”

In the short term — the next four years — the state hopes to have trained 10,000 K-8 teachers in computer science, have certified 1,000 high school computer science teachers, and place a trained administrator in every building, Owen said. The legislature has approved another $5 million for computer science initiatives through fiscal year 2019.

In the long term, Hutchinson hopes more tech companies will move to Arkansas, boosting the economy and providing higher-paid jobs to state residents. There are about 1,600 open computing jobs in Arkansas, according to Code.org, with average salaries around $69,000.

“The objective is that this allows Arkansas to have micro technology hubs, where we can be looked upon … as having innovation companies, technology companies locating here because we have the talent,” Hutchinson told The 74. “The commitment that I have to the students is that whenever you get your coding background, you’re not going to have to go to Silicon Valley. There is going to be those technology companies here in Arkansas that need you.”

Already, he said, the state’s commitment has encouraged some tech entrepreneurs to build their businesses at home. For example, Metova, a mobile application company that opened in Conway, Arkansas, in January 2015 with 60 jobs, later hired an additional 100 workers, and then a few months later opened a second location in Fayetteville.

“This is a company 10 years ago, when it grew, would have moved out of Arkansas because the talent in Austin or other places would have [driven the company] to relocate,” Hutchinson said.

He also has been advocating for expanding computer science education nationwide. As chair of the Southern Regional Education Board in 2015, Hutchinson steered a task force to study the demand for computer science jobs and policies that could strengthen computer science education in member states. The group released its policy recommendations last year.

“It’s probably one of the most rewarding things I’ve done in public service, to see this kind of change in a school environment, motivating young people, giving them greater opportunities and moving Arkansas a step up nationally to be a leader,” the governor said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)