How a Sex Scene in a Young Adult Novel Touched Off Texas’s Latest Culture War

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Kathy May was getting her four kids ready for another day at school in late October when she got an urgent voicemail from a friend.

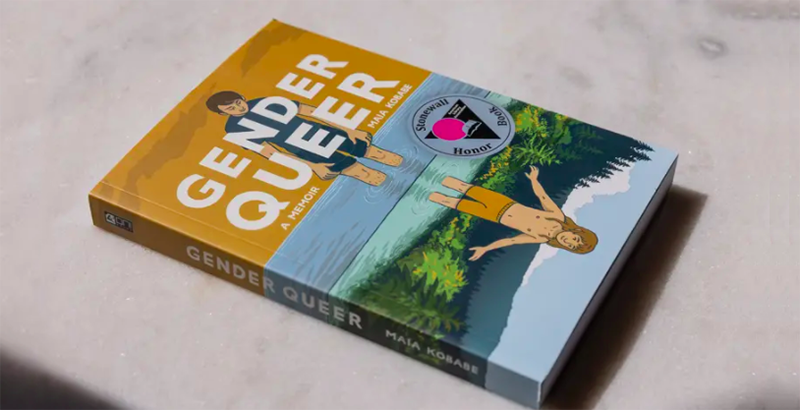

“OMG, OMG, this book,” her friend said, alerting May to a book found by another parent in the library catalogue of Keller Independent School District, where their kids go, called “Gender Queer: A Memoir,” by Maia Kobabe.

“I felt sick and disgusted,” May said, recalling text messages her friend sent her showing sexually explicit illustrations from the book. She was angry that any kid could access that kind of book in a public high school without their parents’ knowledge.

The 239-page graphic novel depicts Kobabe’s journey of gender identity and sexual orientation. Kobabe, who is nonbinary, said it was written to help others who are struggling with gender identity to feel less alone. The book also explores questions around pronouns and hormone-blocking therapies.

“I can absolutely understand the desire of a parent to protect their child from sensitive material. I’m sympathetic to people who have the best interest of young people at heart,” Kobabe, the 32-year-old author based in California, said in an interview with The Texas Tribune. “I also want to have the best interest of young people at heart. There are queer youth at every high school — and those students, that’s [who] I’m thinking about, is the queer student who is getting left behind.”

May didn’t read the book, but what she saw — a few pages of explicit illustrations depicting oral sex — was disturbing to her. It took less than a day for May and other parents to get the book removed from the district. May tweeted that same day that after school officials had been notified, the book was removed from a student’s hands.

“Gender Queer” has become a lightning rod both nationwide and in Texas among some parents and Republican officials who say they’re worried public schools are trying to radicalize students with progressive teachings and literature.

Most recently, Gov. Greg Abbott and another GOP lawmaker have questioned the book’s presence in schools. Abbott has called for investigations into whether students have access to what he described as “pornographic books” in Texas public schools. And last month, state Rep. Matt Krause, R-Fort Worth, sent a list of some 850 books about race and sexuality — including Kobabe’s — to school districts asking for information about how many are available on their campuses.

Across the state, books that tackle racial issues such as “Out of Darkness” by Ashley Hope Pérez and “New Kid” by Jerry Craft have been pulled from shelves after parental complaints. Leander ISD removed six books in the spring, including “In the Dream House” by Carmen Maria Machado, which depicts an abusive same-sex relationship with descriptions of sex. Groups of Texas parents, often sharing information on Facebook groups, have mobilized to find books they deem inappropriate and have them banned from the schools.

The drama has unfolded against the backdrop of a national debate over critical race theory, an academic discipline that holds that racism is embedded in the country’s legal and structural systems. However, the label has been used by some Republicans to target a broader concern that kids are being indoctrinated by progressive teachings in schools.

Texas lawmakers passed two laws this year, that they labeled anti-critical race theory, to crack down on how teachers can talk about race in the classroom. And the issue has been in play up and down the ballot — and outside of Texas, including a GOP victory for the next Virginia governor, who campaigned on a pledge to ban the teaching of critical race theory.

“We have a problem and need help. Our district has a ton of leftist teachers, librarians and counselors who push this plus SEL/CRT. It’s literally a district run wild,” May wrote in a tweet thread, where she shared the sexually explicit illustrations from Kobabe’s book. SEL is short for social and emotional learning, and CRT is short for critical race theory.

“Please help us make parents aware of the danger of the cultural changes our society is making, when people say they’re going after our kids, you need to listen, because they are,” she said in her tweet.

The book

The graphic novel “Gender Queer” traces Kobabe’s own experiences growing up, as the author, whose pronouns are e/em/eir, struggled to identify as gay, bisexual or asexual.

At one point in the book, the author compares gender identity to a scale that was tilted toward being “assigned female at birth,” despite Kobabe’s efforts to be seen as gender neutral. The opposite side of the scale had other factors illustrated with lighter weights, such as “short hair” and “baggy boy clothes.” The image included in the book showed a person trying to add heavier weights labeled “top surgery,” “hormones” and “pronoun” to try to balance the scale.

“A huge weight had been placed on one side, without my permission,” Kobabe wrote. “I was constantly trying to weigh down the other side. But the end goal wasn’t masculinity — the goal was balance.”

While there are illustrations of sexual content in the novel, Kobabe said that students need “good, accurate, safe information about these topics” instead of “wildly having to search online” and potentially stumble across misinformation.

Kobabe, who recommends the book to high school students or older, said there are other novels that have been in high school libraries for years about sexuality, relationships or identity. Kobabe also believes “Gender Queer” in particular became a flashpoint because it is an illustrated comic instead of just text, and that it would not have been singled out so quickly had it been released before the era of social media.

“A person can more quickly flip it open, see one or two images that they disagree with and then decide that the book is not good without actually reading it,” Kobabe said. “To people who are challenging the book, please read the whole book and judge it based on the entire contents, not just a tiny snippet.”

But for parents like May, they say their opposition to the novel isn’t about the LGBTQ community. It’s about whether these materials and images are appropriate for children.“The only reason is because they are sexually explicit for minors,” May said.

The parents

When May, a stay-at-home parent, saw the illustrations from Kobabe’s book, she couldn’t believe what she was seeing. She said she and her family moved from California to the more conservative Texas about two years ago so she was shocked to see the “leftism and progressivism” in Texas schools. They landed at Keller ISD, which is a middle-class, majority white district north of Fort Worth with about 35,000 students.

That day, the images from Kobabe’s book were uploaded to a private Facebook group with thousands of Keller ISD parents by another parent, who also contacted the district about the book.

Within minutes of hearing from that parent, administrators removed it “out of an abundance of caution,” Keller ISD officials said. The district had one copy of the book in a high school library. It was removed “pending an investigation to determine how the book was selected and ultimately made available to students.” Keller ISD officials declined to name which school had the book.

But the Keller ISD parents didn’t stumble upon the book by happenstance. They were on the hunt.

The Tarrant County chapter of Moms for Liberty, a nonprofit organization aiming to support parental rights in education, had shared a list of books they identified as problem literature in schools. Keller ISD parents took that list and started combing through their own school library databases to find matches.

Kobabe’s book wasn’t on the Tarrant County group’s list, but it popped up as parents searched key words for titles with words like “gender” and queer.”

The group of North Texas parents first started their efforts in September to expunge what they’ve deemed “pornographic” material in Keller ISD after they found out the district had copies of “Out of Darkness,” an interracial love story.

May said the group initially became worried about “Out of Darkness” after an article surfaced in their Facebook group about a Lake Travis Independent School District parent who furiously confronted their school board about it, saying that it promoted anal sex.

The parents have asked for the book to be removed and are awaiting Keller ISD’s response.

Pérez, 37, an East Texas native who wrote “Out of Darkness,” said there is no depiction of the sex act in her book. The passage the parent was angry about was a reference to a female character being sexually harassed verbally by another character. The book itself is a love story between a Mexican American girl from San Antonio and an African American boy against the backdrop of a deadly natural gas leak explosion in 1937 in New London, Texas.

“One of [the book’s] functions is to make us uncomfortable and I think that I’m really alarmed by the notion that discomfort is dangerous because, frankly, I think we should be uncomfortable about aspects of our history,” she said.

Pérez said the problem she has with this movement to remove books from schools is that parents already can specify to teachers and administrators that they don’t want their children to read certain books — without having to ban it for all kids.

“‘Gender Queer’ is the book that matters for some kid — and if it’s not there, it can’t give the sense of not being alone,” Pérez said.

The politics

A day before the book was discovered at Keller ISD, Krause, the Republican representative from Fort Worth, launched an inquiry into certain public school districts over the types of books they have, particularly if they pertain to race or sexuality or “make students feel discomfort.” The lawmaker has said the inquiry could help with compliance with the new anti-critical race theory laws passed this year.

Krause, a member of the hardline conservative House Freedom Caucus who chairs the House General Investigating Committee, sent out a list of some 850 books, asking that schools identify whether they have copies on campus. Krause has said he will not offer specifics related to how he developed or got the list of books, saying he does not want to “compromise” a pending or potential investigation by his committee.

Krause’s list includes several books on topics such as race, sexuality and puberty, including Kobabe’s memoir. He did not respond to questions about how he was made aware of Kobabe’s novel. Most of the books on the list were written by women, people of color and LGBTQ writers. Some authors whose works appear on Krause’s list say he’s targeting literature specifically created for children and young adults that helps them feel seen and broadens their worldview.

Titles range from picture books like “I Am Jazz” by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings to popular young adult novels such as “Me and Earl and the Dying Girl” by Jesse Andrews. Books that could show up on a college syllabus also made the list, including “Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women that a Movement Forgot” by Mikki Kendall and “The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness” by Michelle Alexander.

The Texas Education Agency said in a statement that “TEA does not comment on investigations that it may or may not have opened that haven’t yet closed.”

In an Oct. 29 statement, four days after Krause’s letter to school districts and three days after Kobabe’s book was removed from Keller ISD, state Rep. Jeff Cason, R-Bedford, asked Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton “to start a statewide investigation” into the novel “and others that may violate the Penal Code in relation to pornography, child pornography and decency laws.” Cason also asked Paxton to look into “the legal ramifications” for school districts that approved such books.

Neither a spokesperson for Cason nor the lawmaker’s office responded to a question regarding how Cason became aware of the book. And the attorney general’s office has not responded to repeated requests for comment.

Meanwhile, Abbott has asked state education officials to develop statewide standards for blocking books with “overtly sexual” content in schools, specifically citing books by Kobabe and Machado. The governor most recently asked the TEA to investigate criminal activity related to “the availability of pornography” in schools — though it’s unclear why Abbott asked the agency instead of the state’s policing arm.

Heads of the TEA and State Board of Education, in response to Abbott’s request to develop statewide standards, said in statements that they planned to comply.

Christine Malloy, the Keller ISD parent who first alerted the district about her concerns with the book, said they’re happy their work on the issue has apparently grabbed the attention of state leaders.

“The fact that the state governor got involved should show people that it’s an alarming issue,” she said.

But Democrats have criticized the movement as attempted censorship and the latest attack by conservatives on the LGBTQ community and communities of color.

“We should be working to build the most inclusive Texas — not targeting our diverse populations,” said state Rep. Mary González, a Clint Democrat who chairs the LGBTQ Caucus. “It is also highly concerning that these attacks are now being aimed at our education system, which for a long time has been a sacred space for nonpartisan politics.”

Houston Democratic state Rep. Harold Dutton, chair of the House Public Education Committee, said in a Nov. 1 letter that Krause’s book inquiry was “at worst … a bald political stunt that callously blurs the distinction between governing and campaigning.” Krause is running for attorney general.

The backlash

But the scrutiny over school library books, which is largely being driven by white parents, is already a nationwide political phenomenon.

Emboldened by the debate around “critical race theory,” while piggybacking off of a furor by many conservative parents over school mask mandates, Moms for Liberty, was founded in Florida in January 2020. It has grown rapidly with about 60,000 members across the country, aiming to “stand up for parental rights at all levels of government.”

Malloy said the pandemic sending kids home for virtual learning gave many parents a better look at what they were being taught.

“2020 is behind it. I think it was a gift,” Malloy said. “It gave us all time to pay attention to what’s going on, what our kids are being taught — what they were seeing.”

Mary Lowe, chair of the Moms for Liberty Tarrant County chapter, said the main focus of her chapter right now is to get rid of sexually explicit books in schools regardless of whether “the content aligns with one sexual preference over the other.”

If parents want to “expose” their children to those kinds of books, they can go to a public library, she said.

The Tarrant County chapter launched around July and has amassed about 1,700 members since, Lowe said.

Lowe said she has meetings with different superintendents in Tarrant County to talk about what they can do to remove these books.

“Moms for Liberty has a strong stance that there are an enormous amount of literary books that are more aligned with academics and expanding the mind without such a heavy focus on sexual content,” she said.

The broader issue, including what’s to come of those statewide standards in the coming weeks, is a concern for some LGBTQ advocacy groups that argue this is just the latest example in a pattern of Republican officials attempting to single out LGBTQ kids in the state — and how that may impact families and workers.

“If you have a kid who’s part of the LGBTQ community, you could have them asking: Is this a safe place for my kid?” said Jessica Shortall, managing director of Texas Competes, a coalition of more than 1,200 Texas employers, chambers of commerce, tourism bureaus and industry association that advocates for equality. “And then you have people who know and love LGBTQ people but maybe aren’t in that community asking themselves: Does this place represent my values?”

Brian Lopez is an education reporter and Cassandra Pollock is a politics reporter at The Texas Tribune, the only member-supported, digital-first, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans about public policy, politics, government and statewide issues.

Disclosure: Facebook has been a financial supporter of The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan news organization that is funded in part by donations from members, foundations and corporate sponsors. Financial supporters play no role in the Tribune’s journalism. Find a complete list of them here.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)