How a Newark Monastery Trains Young Men in School — and Life

The Seventy Four marks School Choice Week (Jan. 24-30) with a series of stories celebrating educational options and innovation. Read our coverage here.

(Newark, New Jersey) — That the students are the ones running the show at St. Benedict’s Preparatory School is evident from the moment the day begins.

During school-wide morning meetings, student leaders scan the crowded gym to make sure their younger peers are paying attention to the presentations. Teenagers are responsible for leading the school in daily Bible readings and presenting their own team and club announcements in front hundreds of students and teachers.

When no one from the freshman basketball team volunteers to report the results of their recent game, they are chided by school administrators.

“It’s important that you not ignore one another’s successes,” Father Edwin Leahy, a Benedictine monk and the school’s headmaster, told the group. “Announce the scores of your teams…Nobody is having the success that you are having.”

Here at St. Benedict’s Preparatory School, the all-male student body isn’t just handed a prep school education, they are trained to take charge of it. The 7th-12th-grade school is sponsored by the Benedictine Abbey of Newark, a monastery that has embraced a big-hearted mission: to give young boys who may be excluded from opportunities because of poverty and race a rigorous education, emotional support and the leadership skills they need to thrive.

“I feel like people have your back,” Francis Jean-Paul, a 15-year-old freshman, said of the school. “It’s like a family.”

St. Benedict’s efforts were thrust into the national limelight in 2014 after the much-talked about release of “The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace.” The book chronicles the experience of a young man who graduated from the school and went onto to attend Yale University only to be become ensnared in Newark’s drug trade and killed.

But the school has been educating students in families with enough gumption to seek a top-notch private education but not enough money to pay for it for more than four decades. About 85 percent of the 530 students receives need-based financial aid for the $12,500-a-year tuition. Despite their financial circumstances, more than 95 percent of seniors head off to college after graduating, including a regular crop admitted to Ivy League schools.

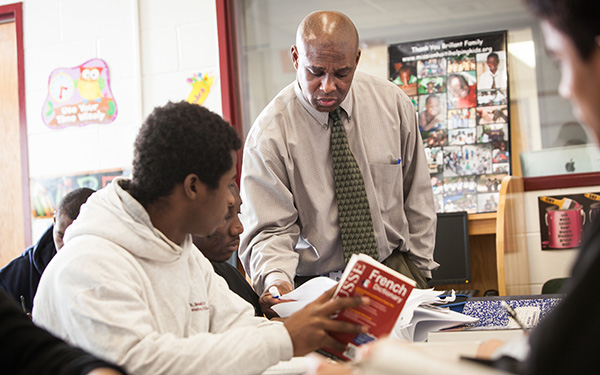

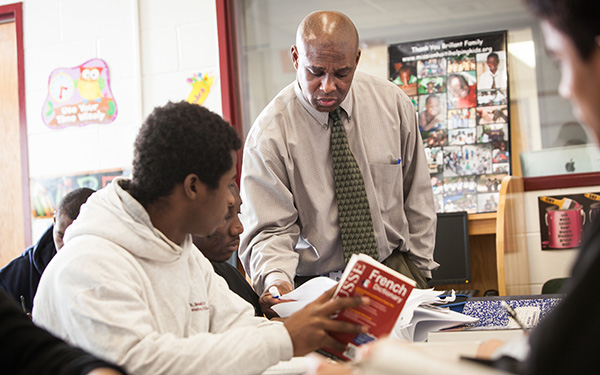

St. Benedict's Preparatory School teacher Frantz Brillant works with students. (Photos courtesy St. Benedict's Prep)

St. Benedict’s began in 1868, initially to help educate an influx of German immigrants in Newark. Their early efforts at education were an outgrowth of their commitment to follow the sixth-century Rule of Saint Benedict, a religious text that offers a vision of what a life of faith looks like for monks living communally.

By the late 1960s, the demographics of the city had changed after white Newarkers fled for New Jersey’s suburbs. In 1967, racial tensions erupted in days of rioting that left 26 people dead. Besides a brief one-year closing in the 1970s though, the school has staked — and held — its ground in Newark, a city that now has an up-and-coming downtown core but whose surrounding neighborhoods still suffer from crime and poverty.

Last school year, close to half of all St. Benedict’s students were African American while a third were Hispanic, 13 percent were white and 7 percent were an undefined race. Many students live in Essex County but some also hail from Union County and even foreign countries. While most students identify as Christian, if not necessarily Catholic, there are also Muslims and other religions represented among the student body, according to Leahy, the headmaster.

Regardless of their religion, the school tries to send the message to all students that they are welcome in this community and that God loves them.

“We don’t do it because they’re Catholic, we do it because we’re Catholic,” Leahy said.

The abbey where the monks sleep is connected to the school building, which means the school is always open—a phenomenon administrators compare to a “24-hour diner” style of education. In fact, about 65 students stay at the school at any given time either because they live too far away to commute every day or because of extreme circumstances in their life at home.

St. Benedict’s school year runs 195 to 200 days of the year—longer than many traditional public schools. Students start in July with a five-week semester and take an intensive core class such as math and another elective. The next two semesters students attend regular classes in a block schedule pattern. At the end of the year, they embark on an experiential learning project, which might include urban gardening, community service or cooking among other options.

Some older students also take freshmen students on a five-day hike through some 50 miles of the Appalachian Trail in the mountains of New Jersey as a class-bonding exercise.

Students at St. Benedict’s tackle many of the same academic subjects that other private school kids learn. During a recent visit, high school seniors debated in college seminar-style the Freudian influences in the classic tale of “Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.” Other students mustered up interest in the different types of tissue in an anatomy class while freshman learned about metaphors and foreshadowing in literature.

What is distinctive about St. Benedict’s is its culture, which holds student leadership and a sense of community in high esteem.

“They are responsible for the day-to-day operations. They run the place,” said Leahy. “Most schools run from the top down…It doesn’t work that way (here).”

That means that students form their own companies to clean up the classrooms, take out the trash and shovel the snow. They interview for jobs at the companies and organize themselves to get the work done. The pay for the teenagers is minimum wage, but the responsibility it instills in the students is priceless, administrators said.

The emphasis on leadership is also evident in its student government structure. The young men are separated into sections and self select leaders who are in charge of making sure students are doing what they are supposed to do. If a student, for instance, has been particularly rowdy or absent from morning meetings one of those leaders may recommend some sort of disciplinary action.

“We tell them what’s acceptable and not acceptable,” said Bruce Davis, 17, St. Benedict’s top senior leader. Davis, who aspires to be a doctor of physical therapy, said it took time to adjust from being a regular student who jokes with his classmates during class to the one in charge of the whole student body outside of it.

“I’ve got to switch (when) it’s time for business,” he said.

In recent years, the school has attracted notoriety in New Jersey and beyond. Its well-regarded basketball team made USA Today’s ranking of top high school boys basketball teams in the country and regularly sends players to Division I colleges.

In 2014, two Newark filmmakers released a documentary on PBS and the film festival circuit called “The Rule”, which profiled the school’s success. The film also tackled the death of Peace, the St. Benedict’s alum who was killed after becoming involved in the drug trade. Peace, the son of a single mom and a father imprisoned for murder, had reportedly earned the school’s top academic award when a business executive offered to cover all his college expenses at Yale. The film, and even more so, the book, was widely covered by national media outlets as the tragic ending to an extraordinary person’s life.

This exposure has prompted education leaders outside the state to seek advice from St. Benedict’s administrators. Leahy said the school is considering starting a resource center for other school leaders to learn how they can bring the St. Benedict’s model to their communities.

The national attention being paid to St. Benedict’s has not eliminated its financial problems. The school has a $10 million annual budget but on average only receives half of what it charges in tuition. The school attempts to make up the difference with donations from city foundations, companies and alumni but it still has about $25 million in debt and only $19 million in its endowment, according to Leahy.

For now, St. Benedict’s is focused on developing the minds and hearts of its students. During that recent school-wide morning meeting, assistant headmaster Michael Scanlan used Jesus’ example to implore students to help other people even when it’s difficult or a way out tempts them.

“It’s easy to hide behind the rules,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)