How a Manhattan High School’s Turnaround Story Could Shape Trump’s (and Clinton’s) Education Plan

In 1995, the corner of East 67th Street and Second Avenue on Manhattan’s Upper East Side marked the intersection of privilege and pandemonium. Located just a few blocks from Central Park, the area had a long history as the home of wealthy elites, including the accomplished Rockefellers, the politically powerful Roosevelts and even Ivana Trump, the ex-wife of current GOP nominee Donald Trump.

But the high school at 67th and Second, Julia Richman, did not share in the neighborhood’s prosperity and opportunity. Rather, it was considered one of the worst schools in the city—so dysfunctional and violent that veteran educators nicknamed it “Julia Rikers.”

That changed in 1995, when the city embarked on what was, at the time, a bold, unproven experiment. Julia Richman was split into six learning communities, an innovation that transformed the school and helped lead a broader movement for small schools that attracted the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which hailed such environments as the future of high school in America.

Today, New York City students have their pick of small high schools, in part because of the millions donated by the Gates Foundation to try to replicate the reforms at Julia Richman and other campuses.

“Even if you want to go to your neighborhood school, you have to choose it. New York City is revolutionary. Julia Richman was on the forefront” of that change, said Thomas Toch, an education policy expert at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy.

While the Trumps followed the lead of many other wealthy families and chose private schools for their children, Donald Trump has begun to shape an education platform that could affect millions of students who don’t have such options.

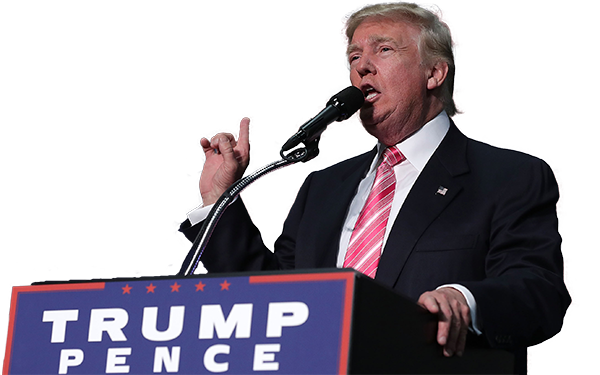

“As your president, I will be the nation’s biggest cheerleader for school choice,” Trump said at an Ohio charter school earlier this month, adding a few specifics to an education stump speech that had started to take shape in August.

“When we reform our tax, trade, energy and regulatory policies, we will open a new chapter in American prosperity,” he said in Michigan on Aug. 8. “As part of this new future, we will also be rolling out proposals to increase [school] choice and reduce cost in child care… I will unveil my plan on this in the coming weeks, that I have been working on with my daughter Ivanka and an incredible team of experts.”

Whether they know it or not, the existence of today’s current educational choices has been greatly influenced by the successful turnaround story of Julia Richman, located just blocks from where Ivanka grew up.

A Manhattan experiment

Ann Cook, a founder of one of the small schools housed in what is now called the Julia Richman Education Complex, captures the high school’s transformation in Creating New Schools, a book about public education in New York City and Boston.

Julia Richman opened in 1913 as an all-girls school that at first focused on commercial skills such as typing and stenography but later expanded to include Latin, Greek and the classics.

It was soon considered one of the best magnet schools for young women, drawing students from across Manhattan and beyond.

After a lawsuit challenged single-sex education in New York, Julia Richman started accepting male students in 1968. The school began to decline, and by the early 1990s, only 37 percent of its students graduated in four years and fewer than three-quarters attended school every day. By 1993, the school had appeared on the state’s list of failing schools for 14 years and was regularly included on the school board’s short list for closure, Cook recounted.

Discipline and violence were significant problems. The school used a mesh cage near the vice principal’s office to hold troublemaking students until the police arrived, or to separate students who were fighting, Cook reported. Residents and local store owners complained about the disorder the students caused in the neighborhood.

Newsday reported that in 1990, the police instituted a policy of stationing extra officers in the area on Halloween, after a group of students “terrorized the Upper East Side” the year before.

“When we see packs of teenagers out on the street during the day, we know they’re up to no good, and we’re going to sweep those kids up and steer them to Julia Richman,” Michael Collins, a police department leader, told the newspaper.

Even the decades-old building was a disaster. One custodian told Cook that graffiti was splattered across the walls, bathroom partitions had been torn down and the leaky roof had damaged almost every floor, rendering some rooms unusable.

“There was a need to rethink the comprehensive high school,” said Toch. “These tend to be large, impersonal places. They are typically unattractive and almost prison-like in their culture.”

In 1993, the Board of Education stopped sending ninth-graders to Julia Richman, and by 1995 the school was completely restructured, with six autonomous schools that controlled their own hiring, curriculum, schedule and overall organization.

Why smaller was better for students

The new Upper East Side complex would include young and older students, but the total enrollment at each school would not exceed 300.

The complex also formed a building council to make decisions that affected all the schools, such as combining their sports teams and coordinating a schedule for common areas. Early on, the council decided to remove metal detectors that screened students as they entered the building, in an effort to create a warmer environment.

Early statistics showed a dramatic transformation.

By the 1995–96 school year, the new school complex had higher attendance rates than the old Julia Richman High School, even though its students were more likely to qualify for free lunch, according to a 2002 study in the American Educational Research Journal. The percentage of juniors passing the reading portion of the state Regents English exam increased by one percentage point, while the passing rate in math rose by nearly 20 points. Writing scores declined by about four percentage points that year, according to the study.

The next school year, the passing rates on the reading, math and writing tests were 93.6 percent, 79.4 percent and 85 percent, respectively — much higher than the old Julia Richman High School scores, the study said.

Those results created a ripple effect across the education world. Julia Richman became the subject of newspaper stories, research and policy papers, and books.

In the following years, New York City rapidly expanded its efforts to form new, smaller high schools, particularly under the Michael Bloomberg administration. When the Gates Foundation announced in 2003 that it was devoting $51.2 million to starting 67 small high schools in New York City, it cited the Julia Richman Education Complex as “one of the most successful high school turnaround stories in the country.”

Several research studies subsequently found that smaller schools were more likely to graduate students in four years, though their effect on classroom achievement is less clear. Critics have argued that the implementation of small schools has led to unnecessary closures in the traditional public school system and that the success of small schools is not uniform.

In recent years, the Gates Foundation has shifted away from supporting small schools in favor of improving teacher instruction, academic standards and classroom technology.

But the growth of the small-schools movement buttressed by the results of Julia Richman has led to lasting, if not permanent, changes in school districts across the country — changes that can be traced back to the Trumps’ old neighborhood, changes that may have made an impact on the girl who went on to advise her father on national policy.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)