How 2 Business-Savvy Nonprofits Are Breathing New Life Into Philadelphia’s Struggling Catholic Schools

Philadelphia

A friend and relative of many alums, Foster, 17, had little doubt she would enroll at West Catholic rather than her neighborhood high school when she graduated from middle school three years ago.

But had it been just two years earlier, Foster might not have been able to follow in their footsteps.

In 2012, the school was one of nearly 50 put on the chopping block by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia in the face of a 35 percent drop in Catholic school enrollment over the previous decade. At West Catholic, the building that had once held about 3,000 students had just 236.

But today, due to the efforts of entrepreneurs and educators — and a surprising willingness by the archdiocese to hand control of every high school and more than one-quarter of its K-8 schools to two nonprofits — things have turned around dramatically.

Instead of declining, enrollment has soared (at West Catholic, the student population has almost doubled, to 410); instead of budget cuts and ballooning debt, some schools are boasting of surpluses; and instead of charging tuition that is out of reach for poor families, the schools are providing more financial aid.

“So many partners rallied behind this rebirth of Catholic schools,” said Samuel Casey Carter, CEO of Faith in the Future, the foundation running the archdiocese’s 17 high schools. “Catholic schools provide a low-cost opportunity for us to create a high-quality educational option today.”

Spurring the revitalization was a combination of a business approach to school administration and a revamped state tax credit scholarship program that encourages wealthy donors to help needy students cover their tuition costs.

Now, Carter is hoping to expand its reach through federal investment in a voucher program proposed by President Trump.

Though the first Catholic schools opened in Philly in the late 18th century, their heyday was the first half of the 20th century, as an influx of immigrants sent enrollment soaring. The student population exploded from 68,000 in 1911 to 271,088 in 1959, according to the archdiocese.

Those flourishing schools came to define Philly’s neighborhoods, where residents often identified themselves by the parish they attended.

But in the past 50 years, enrollment dropped dramatically, the result of a declining city population and, more recently, competition from tuition-free charter schools. By 2011, the archdiocese had just 68,070 students, the same as 100 years before, in 177 schools.

As student enrollment and tuition payments declined, local churches increasingly had to subsidize their schools. Dozens of schools found themselves with significant deficits, while their parishes were juggling huge debts of their own.

It was an unsustainable financial situation, and in response, five years ago, the archdiocese appointed a blue-ribbon commission to chart a course for the city’s Catholic schools — many of which were struggling, with no viable plan for recovery or future growth. The commission recommended closing or consolidating 40 to 45 of about 156 elementary schools and four of its 17 high schools, including West Catholic.

In the outcry and negotiations that followed, the commission and Archbishop Charles Chaput agreed to allow schools that could present solid viability plans to stay open.

Independence Mission Schools, which had been founded by wealthy donors and was already running one Catholic school in an extremely poor neighborhood, took over the operational and financial management of 15 K-8 schools in the city and suburban Delaware County. The newly created Faith in the Future foundation assumed control of 17 high schools and four special education schools.

Coincidentally, at the same time, Pennsylvania was preparing to send Philadelphia’s Catholic schools a legislative lifeline.

In 2001, the commonwealth had created the Educational Improvement Tax Credit program, which gave businesses tax benefits for donating to nonprofits that could award up to $60 million in K-12 scholarships. Then, in 2012, Pennsylvania approved the Opportunity Scholarship Tax Credit program, giving additional tax credits for donations to private school scholarships for students in underperforming public schools. Since then, about three-quarters of the funds for the tax credit programs have gone to religious schools, according to a recent report.

The result: Two outside organizations have managed to turn around a centuries-old school system using modern-day business practices — a feat that few dioceses around the country have been able to accomplish.

From 2012 to 2015, scholarship donations to Independence Mission Schools increased from $1.8 million to $9.7 million and enrollment grew from 3,800 to 4,800, according to a recent financial report.

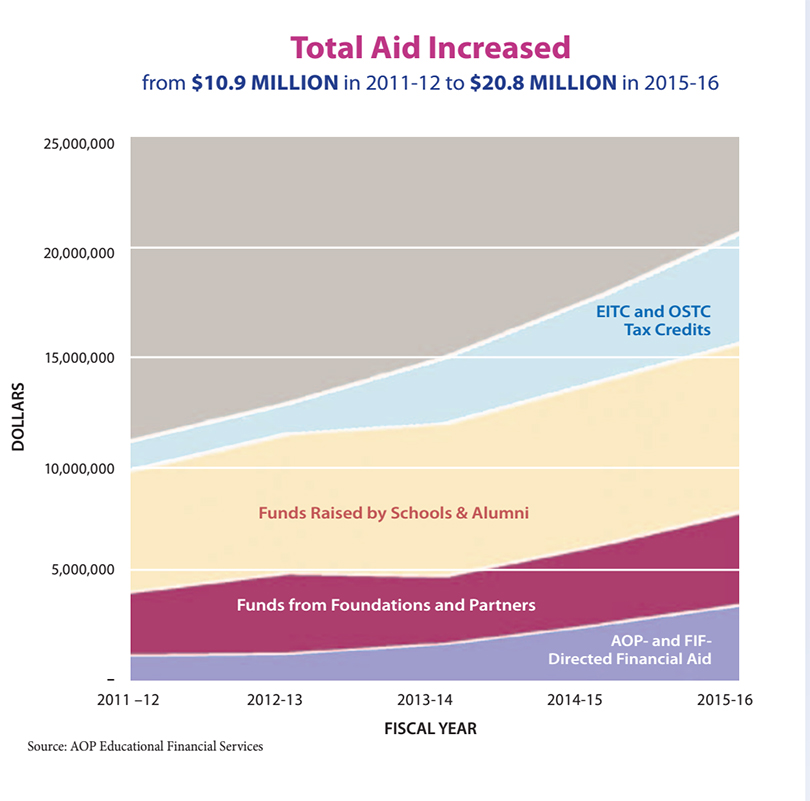

For Faith in the Future, better fundraising from alumni and the tax credit scholarship programs allowed for a boost in financial aid from $10.9 million in the 2011–12 school year to $20.8 million in 2015–16. The annual decline in student enrollment has slowed, and the foundation projects modest growth for next academic year.

Foster, for one, has benefited from the tax credit scholarship program and two other scholarships that together cover half the cost of West Catholic’s tuition and fees, according to her mother.

“It really has been helpful for our family,” Sheree Foster said. “You want to give your children the best.”

One of the first challenges for Faith in the Future was identifying the best people to run its schools in the new era. Instead of religious or lay leaders — who were still invaluable in heading up religious instruction — Carter wanted business people skilled in the fundraising and marketing that were essential to the schools’ survival.

Banker Denise Kassekert, for example, was serving on the board of John W. Hallahan Catholic Girls’ High School, her alma mater. She volunteered to “help out” while the board searched for a new president — and before she knew it, she was being tapped to lead the school.

“The thing that I felt most happy about was being with the students. And that came very unexpectedly for me, coming from the business world,” she said. “To be able to watch them get through their day, be joyful, participate in activities, it was a very emotional experience.”

Another challenge was making each school responsible for setting its own budget, hiring its own educators, and conducting its own marketing campaigns, while creating a centralized purchasing system and streamlining accounting and tuition collection.

The foundation also used the boost in fundraising to make capital improvements, repurposing unused convents in some schools as dorms for international students, who often pay full tuition.

“[We tried] to figure out how can you prepare and build on the tradition that was existing while getting schools to understand that the business conditions have changed and so, therefore, they need to be operated and governed differently,” Carter said.

That dual approach of preserving tradition while changing operation and governance applies to academics as well — and is personified by Carter himself.

A former Benedictine monk, Carter taught at a Catholic boarding school in Rhode Island before becoming president of National Heritage Academies, a for-profit company that operates charter schools in nine states and serves more than 50,000 students. As an education consultant, he has advised clients such as the Cristo Rey Catholic school network and KIPP Public Charter Schools, as well as for-profit school operator K12 Inc.

He has written two books on education: No Excuses: Lessons From 21 High-Performing, High-Poverty Schools and On Purpose: How Great School Cultures Form Strong Character.

While preserving traditional Catholic education, with its rigorous academics and deep religious roots, was a must, Carter was also determined to add education reform elements of the type found in the charter schools that have given the archdiocese’s schools such stiff competition.

To raise academic standards, the foundation started focusing on digital assessments to track students’ progress in reading and math against national norms three times a year. Those scores are used to identify groups of students who might need extra support in, say, critical reading and offer more professional development to their teachers.

Carter is also open to having students at foundation schools take state standardized tests, which Catholic school students in Philadelphia currently do not do.

Going forward, the foundation wants to continue to look at ways the network can support the schools’ individuals needs — whether it’s technology upgrades, social services, or more educator training.

“In the very beginning, [the Faith in the Future model] was an experiment that needed to be tested, and now that experiment is proven to be worthy, it’s an experiment that now needs to be scaled,” Carter said. “What we want to be able to do is to identify those specific services that we can best offer that will then really do two things: allow each school to grow on a financially sustainable basis and allow each school to continuously improve their instructional program.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)