House Hearing on Brown v. Board Legacy Focuses on School Choice, Federal Discipline Guidance

A House Education Committee hearing billed to be about the unfulfilled legacy of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case focused in large part on ongoing disputes over school choice and regulatory actions taken by the Trump administration.

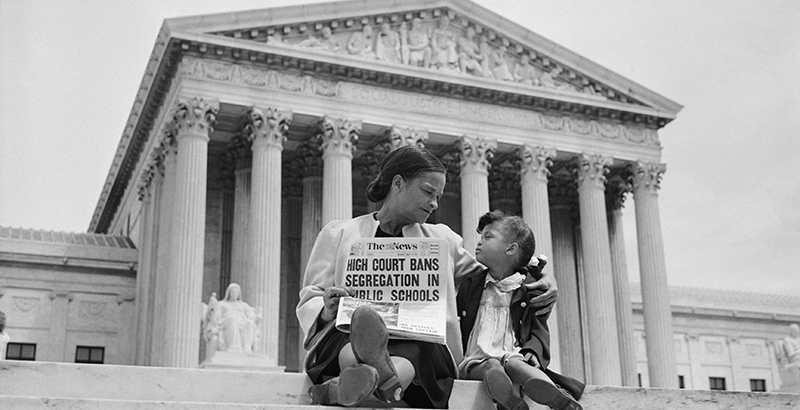

Sixty-five years after the decision banned segregated schools in the United States, schools remain as segregated as ever, with a 2016 Government Accountability Office study finding the number of schools with high percentages of black or Hispanic students growing in recent decades.

Democrats in particular homed in on Education Secretary Betsy DeVos’s moves to withdraw two Obama-era guidance documents, one that helped school districts voluntarily integrate without running afoul of the law, and another that encouraged districts to limit the use of exclusionary discipline and pinpoint racial disparities in their discipline data.

Overturning the guidance documents sent a signal that the federal government doesn’t care about the issues, and left districts on their own, witnesses said.

Ending the integration guidance in particular “sends the message that the federal government is not forward-looking about helping districts create more diversity, and it also creates more confusion” about what schools can do, said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute, a think tank.

Republicans, meanwhile, defended DeVos’s actions, arguing she is still appropriately enforcing civil rights protections. And they called a witness who described a chaotic and violent high school experience in Queens and was sharply critical of the discipline guidance.

“The Obama-era guidelines aren’t social justice. It is state-mandated foolishness,” said Dion Pierre, who noted, in response to a question, that he had reached out to committee Republicans himself.

On school choice, Democrats discussed research that has shown charters are more segregated than district schools, and asserted that public funding of schools of choice means less funding for essential programming for children of color.

Republicans, for their part, said the legacy of Brown should be a school choice option that gives families a way out of low-performing schools.

“I think it’s important that we have choices available for parents and for students who today cannot access a great education,” said Rep. Lloyd Smucker, Republican of Pennsylvania.

Integration and school choice “are not principles that need to compete with one another,” he added.

Leaders at all levels of government can take action to promote integration, expert witnesses said.

At the local level, leaders should ensure that there are high-quality, equitable education options around the city, transportation for students to reach those schools and fair admissions processes. Those policies have worked, although seldom without controversy, in places like San Antonio, Texas, and Hartford, Connecticut, experts said.

Besides reinstating the discipline and integration guidance documents, there are other actions the federal government can take, like increasing funding for magnet school programs, adding money for Title I school improvement, and requiring states and districts to fully report all required achievement and spending data under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

It’s essential for the federal government to play a role in school integration, New York City Chancellor Richard Carranza said. (He acknowledged ongoing problems in the lack of integration in the city’s elite high schools and said city officials are working to overturn a state law that requires admissions decisions to be based on just one test.)

“The role of the federal government is critical in keeping us accountable, in keeping states accountable. This can’t be a one-by-one effort; it has to be a systemic effort,” he said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)