Historic Rise in Child Bereavement as COVID, Drugs and Guns Claim Parents’ Lives

Parent deaths rose 25% in 2020 and the virus explains only a fraction of the increase, with accidental overdoses and gun homicides driving that number

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

It’s been two-and-a-half years since Reid Orlando lost his mother and he continues to feel the sting. His mom, a single parent and ER nurse of three decades, caught the virus while helping patients during the pandemic’s deadly first wave and did not recover.

Now, every new milestone reminds Orlando of her absence: Landing his first job out of college, his younger brother graduating from high school, even smaller occasions like cooking homemade Italian food on Sunday evenings, a tradition of hers that he still keeps alive.

“My life will never go back to normal,” said the older sibling, who, at 23, stepped up to care for his brother, a high school sophomore, and his 80-year-old grandmother. “But I work my best to try to make it as normal as possible and just put one foot in front of the other.”

Across the country, hundreds of thousands of young people, like Orlando, are navigating the delicate journey of moving forward — whether in school, career or family — after losing a caregiver during the pandemic. As of June 2022, more than a quarter million Americans under 18 had lost a primary caregiver to the virus, according to a tracker maintained by the Imperial College of London.

Yet that already staggering tally does not fully encapsulate the scope of the issue. During the pandemic, child bereavement rates increased dramatically, a trend only partly explained by deaths due to infection.

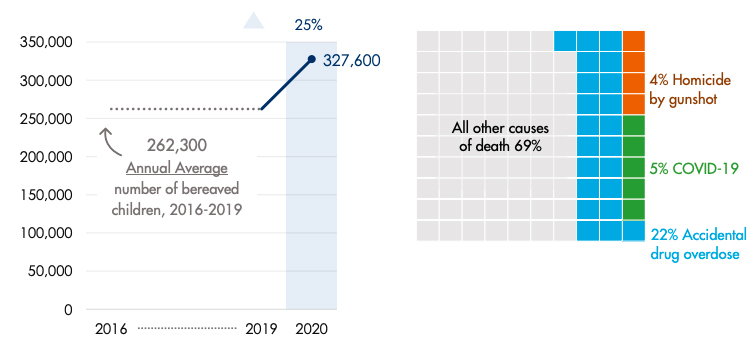

In 2020, the most recent year for which data on all manner of caregiver deaths are available, the annual number of children who experienced the loss of a parent spiked 25%. Between 2016 and 2019, the number averaged roughly 260,000 annually; by 2020 it had reached more than 325,000, according to a report from Judi’s House, an organization that supports bereaved children.

Only 5% of parent deaths in 2020 were from COVID, while 4% were from homicides by gunshot and 22% were from accidental drug overdoses. The latter two causes increased by 41% and 34%, respectively. Parent deaths from health conditions like diabetes and cancer also rose.

“It wasn’t just COVID, we were seeing increases across the board,” said Michaeleen Burns, clinical director of Judi’s House, at a Nov. 1 event hosted by the New York Life Foundation.

“This trend is not stopping anytime soon,” she added. While the data are not yet finalized beyond 2020, she suspects “we will continue to see that increase in 2021 … and most likely we’re going to continue to see it into 2022.”

With recent test score results shining a light on students’ pandemic learning setbacks, the overwhelming bereavement numbers offer a sobering reminder of the long-lasting social-emotional injuries young people are facing alongside their academic losses.

Vulnerable communities hit hardest

Children who are Black or Indigenous — groups that have been subject to catastrophic medical racism in the past — experienced the death of a caregiver due to COVID at outsized rates: twice and nearly quadruple the rate of white youth, respectively.

“The loss is disproportionate,” said Catherine Jaynes, researcher at the COVID Collaborative, an organization that has tracked the pandemic’s toll on children.

In New York City, which became the global epicenter of the pandemic during the early months of 2020, deaths were concentrated in high-poverty neighborhoods, resulting in crushing levels of grief at certain K-12 campuses.

“We had a school community that they lost, I think over 100 family members in one school building. Could you imagine the amount of trauma that that one school was dealing with?” said Tamara Mair, director of interventions for the New York City Department of Education. She declined to specify which campus she was referring to.

The nation’s largest school district held dozens of live consultations to help educators train in grief responsiveness. David Schonfeld, founder of the National Center for School Crisis and Bereavement, led many of those sessions and said he was “deeply impressed” with the city’s response.

Zooming out beyond COVID, children living in West Virginia are more likely than those in any other state to experience the death of a parent by the time they turn 18. Roughly 1 in 8 there, where drug overdose rates are the highest in the nation, go through the trauma of caregiver loss compared to a national rate of 1 in 13.

At the same time, there may not be adequate support systems in place to help those grieving young people, said Burns.

“There’s huge swaths of the country where there’s the highest concentrations of childhood bereavement where there are no resources,” the Judi’s House clinical director said.

‘The loss … is still present’

Bereaved youth face elevated risks of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and early death, studies show. Even years later, they are more than twice as likely than their peers to show impairments in functioning at school and at home — yet Jaynes says leaders aren’t paying enough attention to the scars many students now carry.

“People are forgetting that … the loss that they experienced is still present in their lives,” the bereavement expert said.

It didn’t take long for people in Orlando’s life to move on after his mother, 56, passed away from COVID in 2020, even as he continued to struggle.

“After the four- to six-month mark, people really start forgetting,” he said. “You don’t want to be the one to reach out like, ‘Hey man, I just really need someone to talk to.’ So a lot of that you bottle in, you jar it.”

But rather than fading, the pain takes on different shapes in the months and years after a parent passes, explained Sallie Lynch, who works at Tuesday’s Children, a nonprofit established to support the young people whose parents were killed in the September 11 terrorist attacks.

“We’ve seen over the last 21 years of our work that a kid’s understanding of death changes at a different age and kids tend to re-grieve,” she said.

Adults should validate children’s pain and empathize, but avoid comparing the loss to their own experiences, advises Schonfeld, the grief expert.

Sam Adams, 19, lives in New York City and lost his younger brother to a rare disease six years ago. Afterward, classmates and educators tried to empathize but sometimes struck the wrong chord.

“I know what you’re going through,” he remembers people saying, but then going on to compare it to, “My dog died, my fish died.”

Stepping up for grieving children

Schools and other youth-serving institutions should also strive to support bereaved children with the “secondary setbacks” associated with their loss, said Burns, of Judi’s House.

“Maybe you had to move homes, maybe you had a loss of income, maybe your primary caregiver is now suffering with their own grief and depression and not able to care for you in the same way,” she said. “It can even lead to early mortality for that bereaved child if they’re not given the support that they need.”

But in order to provide financial assistance, counseling or any other type of support, schools first need to identify students who have experienced loss. And Jaynes fears many may be sipping through the cracks.

“There is no systematic way in this country to identify a child that has lost a parent or caregiver,” she said.

She held up Brazil as a counterexample, where there is a checkmark on all death records to indicate whether the parent has left a young person behind.

In the U.S., schools could include screeners to diagnose whether their students have experienced the death of a parent, she suggests, so educators are aware of the trauma some of their children may carry.

“Is there a way as a country that we can step up for these children, whether it be COVID loss or any type of loss, to actually support them going forward?” Jaynes asked.

Such mitigations, said Burns, could help grieving youth for years to come.

“Long after the pandemic fades, we are still going to need to be able to support bereaved children,” she said.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)