Hernandez: Career and Technical Education Is Valuable for All Students — Not Just the Ones Who Bypass College

But students across the academic spectrum — even bachelor’s degree holders — are battling to find their footing in today’s economy. Our schools and colleges are good at sorting students, but few economically empower them.

Career preparation is good for all kids, not just “those” kids. And if we want to build ladders to better opportunities, career preparation needs to be featured in our schools and colleges.

National career-matchmaking firm GradStaff surveyed 503 recent college grads seeking their first entry-level jobs between May and December 2016. The headline: “70 percent of respondents were either unemployed or working in a full-time non-professional job to make ends meet.”

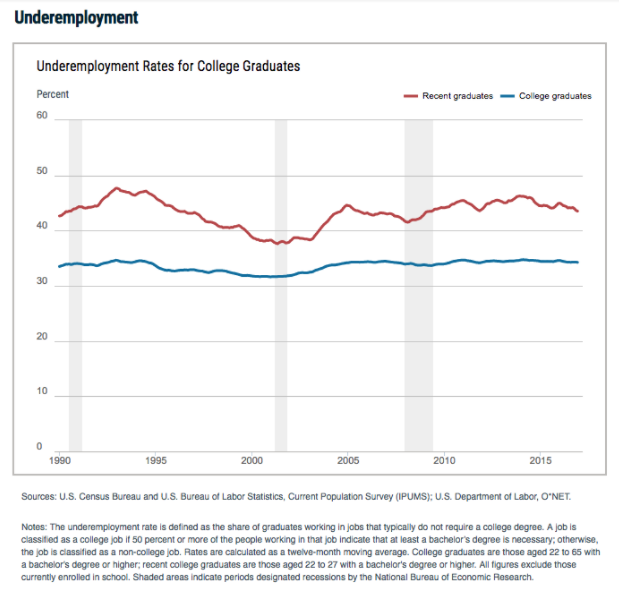

Play that out a few more years and 43 percent of recent college graduates ages 22 to 27 are in jobs that do not require a bachelor’s degree.

My suburban friends are fond of saying things like, “Your kids will be fine no matter what.”

But higher education expert Ryan Craig observes that colleges and universities are falling down when it comes to the “last mile” training students need to make the jump from college to the workplace.

There are a few reasons for this.

First, the job market is shifting. Employers want skills, like project management or Apache Hadoop, in addition to high levels of education. But four-year colleges struggle mightily to think beyond their traditional curricula. If employers can’t get skills, then they ask for more experience and more education, creating a Catch-22 for new grads.

Second, students receive very little support when it comes to career preparation. The median ratio of students to college and university career counseling staff is 1,765 to one. This means most students receive little to no guidance during a time when hiring processes are changing rapidly, like the shift to applicant tracking systems that use algorithms to screen résumés.

Third, tremendous barriers still exist for first-generation college students who lack the means to take an unpaid internship or buy that first work outfit. Internships help students build the social networks and connections that are so critical for job seekers.

And even in 2017, minority job candidates still face discrimination. Harvard researchers recently found that African-American applicants were 2.5 times as likely to get a callback for interviews if they eliminated any clues to their race in their résumés.

It’s time to admit that a bachelor’s degree is simply not enough to help our most successful students — our four-year college graduates — find their way to upwardly mobile jobs and choice-filled lives.

And we have not even begun to talk about the majority of Americans, like those who dropped out of college with student debt or never went at all.

Has our country run out of ideas for how to create opportunity?

We can and should reframe our education agenda around economic empowerment, meaning that all students who want a path to a better life have several ladders they can climb to do just that.

Economic empowerment means helping students find the very best experiences in the classroom and in the workplace. There is a false divide between the college-for-all and career and technical education crowds. Team College-for-All has steadily improved traditional classrooms while generally ignoring career readiness. Team CTE generally sins in the opposite direction. Kids need better experiences on both sides of the playing field, and we need a new generation of leaders that can help us bridge that divide.

For example, Carmen Schools of Science & Technology, a network of four public secondary schools in Milwaukee, offers career preparation programs to all students, no matter where they land on the academic spectrum. (Disclosure: My employer, Charter School Growth Fund, philanthropically supports Carmen Schools of Science & Technology.) In addition to high school classes, Carmen students can earn skills certifications and college credits from Milwaukee Area Technical College. They do health care apprenticeships at Froedtert and the Medical College of Wisconsin hospital system or IT support apprenticeships at local companies. Students who go on to attend four-year colleges can see higher earnings while working their way through school ($12 to $18 per hour, vs. minimum wage) and, perhaps more important, accrue valuable professional experiences and contacts. Early job exposure helps inspire and motivate students to consider higher positions in these fields — and avoid careers that seem less attractive after closer inspection.

Shifting the frame to economic empowerment can also broaden our perspective of what we mean by academic and career readiness. I would argue that Braven, an accelerator that helps low-income college students graduate and land a strong first job, is one model for what CTE will look like in the future if we build programs through the lens of economic empowerment.

The ladders to upwardly mobile careers will take different forms, depending on the intensity of students’ needs. Year Up is a nonprofit that offers a one-year program to 18-to-24-year-olds who are out of school and living in poverty. It reports that four months after completing the program, 85 percent of their students are in professional jobs paying an average of $36,000 per year or enrolled in a post-secondary institution. But their students are not just struggling to get back into school and navigate the workplace. Many are experiencing deep trauma and chaotic home lives. In addition to college and career counseling, Year Up offers wraparound supports and mental health services to help students transition to a better life. It does not fall under the traditional definition of CTE programs, but it is squarely an economic empowerment play.

A shift to economic empowerment means helping students find productive pathways that lead to opportunity and avoiding toxic pathways where the odds are stacked against them from the outset. For example, only 39.3 percent of two-year community college students complete some type of degree (associate’s or bachelor’s) in six years — not great odds. But are there pathways through those institutions, such as a certification in cybersecurity, that have higher chances of completion and lead to upwardly mobile careers? And what does it look like to make those productive pathways transparent for students? The good news is that we have more data than ever to identify productive pathways through college and career. It really becomes a matter of institutional will to grow productive pathways and trim the toxic ones.

We need to stop thinking in terms of chutes, and start building ladders across K-12, higher education, and industry, where economic empowerment for all Americans is the goal.

The opportunity to infuse career preparation throughout K-12 and higher education is spurring educators to try new approaches to school, like the High School of Health Sciences in Wales, Wisconsin, where a student can do an off-campus internship for two full weeks knowing that her Advanced Placement classes are designed to flex around this valuable experience.

In higher ed, the U.S. Department of Education is helping traditional colleges and universities partner with nontraditional providers to find better ways to prepare students for jobs.

And forward-thinking cities are investing in efforts like TechHire, YouthForce NOLA, and CareerWise Colorado to help students transition from classrooms to careers.

In a world where career preparation is good for all kids, we must find more tactical ways like the ones here to connect youth to opportunity — and invest public and private dollars in the educators leading the way.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)