Outside of statements about eliminating the U.S. Department of Education and calling the Common Core a disaster, Donald Trump hasn’t had a lot to say about America’s public education system.

But when speakers hit the Republican National Convention stage in Cleveland this week, some glimmers of the presumptive presidential nominee’s education agenda may start to emerge. After problems convincing “hardly anybody” to participate in a Trump convention — including House members who normally would beg for a moment in the limelight — the list of

convention speakers is a mix of Trump family members, military figures, politicians, business people, public officials, athletes, advocates and celebrities.

In a presidential race for the history books that’s turned on terrorism, immigration and the economy, it’s unlikely K-12 education will consume much of the convention conversation. But if we can’t look forward, we can look back: a handful of the speakers slated to appear in Cleveland are Trump’s former Republican rivals who have previously discussed their education platforms, including in-depth at The 74’s education summit last year in New Hampshire. (Trump did not attend the summit; he instead held his own town hall just a few miles away.)

So if the GOP speakers do bring up education, here’s what they might say. But first, one talking point any one of them could espouse: the demise of the Common Core.

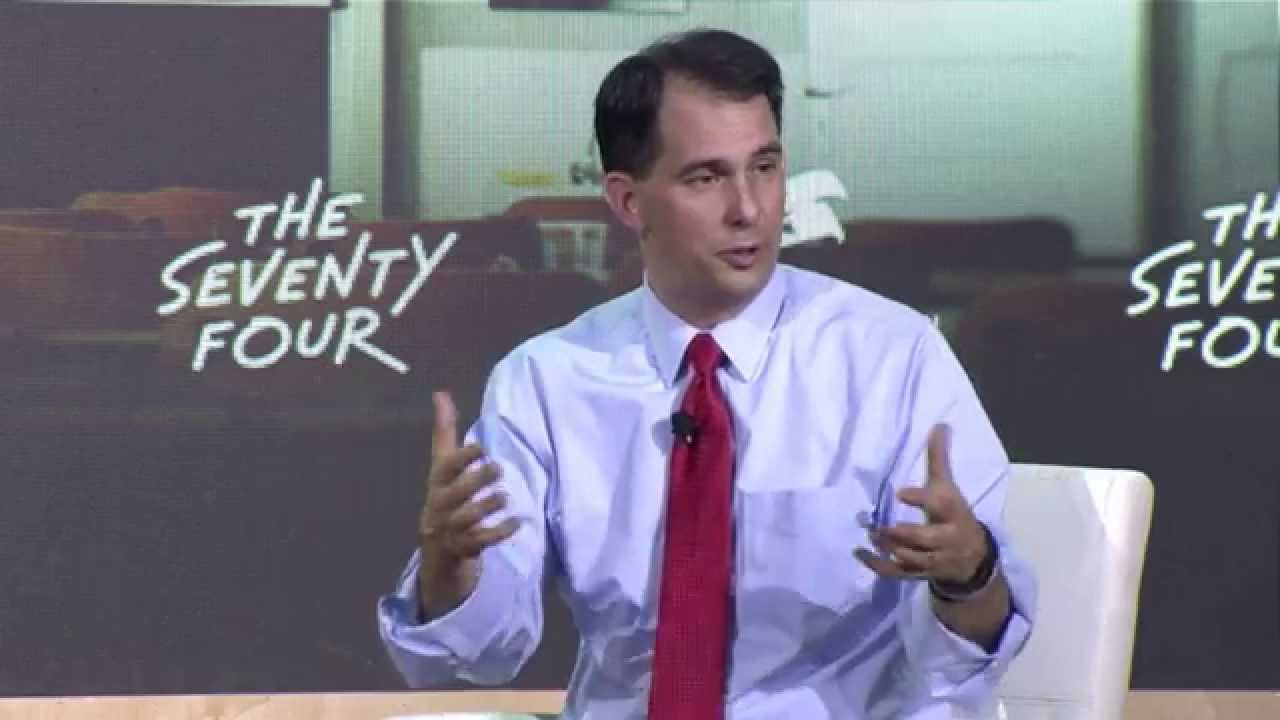

Gov. Scott Walker

A prominent supporter of school choice, the Wisconsin governor helped expand school vouchers by eliminating a cap that limited the program to 1,000 students. But Walker is perhaps best known in the education community for butting heads with public employee unions, including moves to eliminate mandatory union dues, requiring teachers to contribute to their pension plans and health care costs, and reforms to public university tenure protections.

Ultimately, former Republican presidential candidate Walker sees a minimal role for federal involvement in education policy, adding that while federal lawmakers hold an oversized influence on schools, they invest too little.

“Right now, way too much power is concentrated in our federal government,” Walker told The 74. “Instead, we need to push it not just back to the states, but ultimately back to the local level, where school board members, parents, teachers, and others can play an active role in determining our educational outcomes.”

The 74’s Editor-in-Chief Campbell Brown will interview Walker at the convention Tuesday. Check out the GOP Convention Live Blog by The 74 and Bellwether Education Partners for all the latest RNC news.

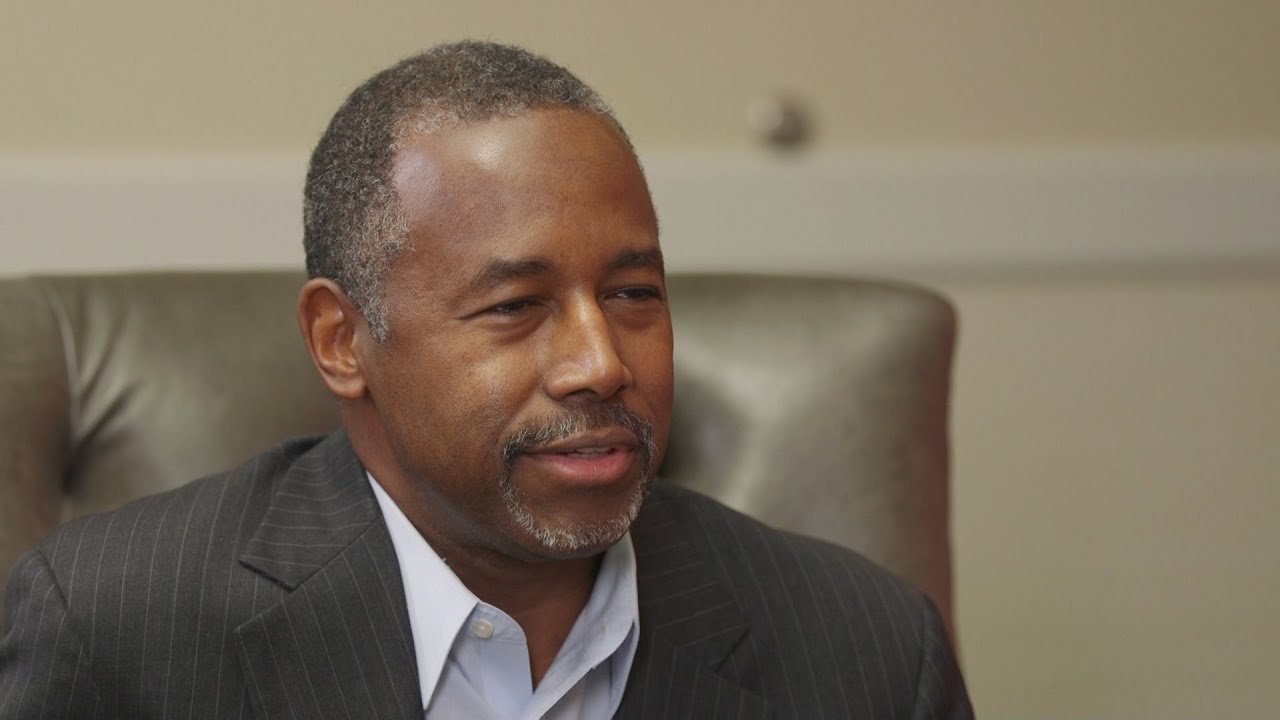

Ben Carson

After Ben Carson dropped his presidential bid, Trump hinted at a prominent White House job for the retired neurosurgeon, saying the one-time rival would be “very involved with education, something that’s an expertise of his.” If Carson were to discuss education in Cleveland, school choice — and more specifically homeschooling — would likely come up.

“We know that the very best education is home school,” Carson said in an interview with The 74’s Campbell Brown last November, before he left the race. “The next is private school, the next is charter schools, and the last is public schools. If we want to change that dynamic, we have to offer some real competition to the public schools.”

Along with hopes to wish the Common Core a “quiet death,” Carson said the federal government’s role in education, including school accountability, has created “nothing but chaos.”

“States will be able to set their own standards, work with their local school districts and work with parents and PTAs,” Carson said of his education platform. “I don’t see a downside in doing it that way.”

Ted Cruz

The Texas senator really, really hates the Common Core. During a CNN debate in March, Cruz called the Obama administration’s Race to the Top funds an abuse of executive power to “effectively blackmail and force the states to adopt Common Core.”

Along with calls to eliminate the U.S. Department of Education and the federal government’s role in K-12 schools, Cruz called school choice, including increasing charter schools and private school vouchers, “the most important reform we can do in education.”

Chris Christie

The New Jersey governor made news last month when he unveiled a new school funding formula that would give each school district the same amount of state per-pupil funding — a move that would shift money from high-poverty urban districts to wealthier schools in the suburbs. While Christie argued “Spending does not equal achievement,” critics of the plan said it would likely hurt low-income students.

Like the other speakers, the governor and ex-Republican presidential candidate has followed a pro-choice, school reform agenda, including performance-based pay for teachers and longer school days and years — two ideas that teachers unions have traditionally opposed.

It’s no surprise, then, that Christie and unions aren’t exactly allies. During a January forum in South Carolina, Christie, who was being discussed as a possible GOP running mate until Trump picked Mike Pence on Friday, said “the single most destructive force for public education in this country is the teachers union.”

Although Christie once supported the Common Core, and New Jersey was an early state to adopt the standards, he later distanced himself, explaining his flip-flop to Brown during The 74’s summit.

“Three constituencies in my state hate Common Core: teachers, parents, students. I stuck with it, I fought for a while against those constituencies,” he said. “I did what I think you’re supposed to do when you lead: Something that looks like a good idea, you give it a try. If it does not work, you can’t be worried about somebody asking you a gotcha question.”

Another U.S. Department of Education-abolisher who believes teachers unions are “the biggest impediments to educational reform in this country,” the Florida senator said in an interview with The 74’s Campbell Brown that parents can more easily influence local and state policymakers than Congress “unelected bureaucrats sitting in a massive building in Washington, D.C.”

Back when Rubio was eyeing the White House himself, he said he didn’t believe the president should have the power to push changes on states and schools — though he acknowledged the school achievement gap largely driven by money.

“Most Americans either have the means to send their children to private schools or can move to a neighborhood with better public options, but low-income people do not, and that’s wrong,” he told Brown. “It’s immoral that the only people in America who have no control over where their kids go to school are low-income parents.”

;)