Grade Inflation ‘Persistent, Systemic’ Even Prior to Pandemic, ACT Study Finds

The results — based on a sample of over 4 million students — provides evidence that grades don’t reflect objective measures of achievement

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

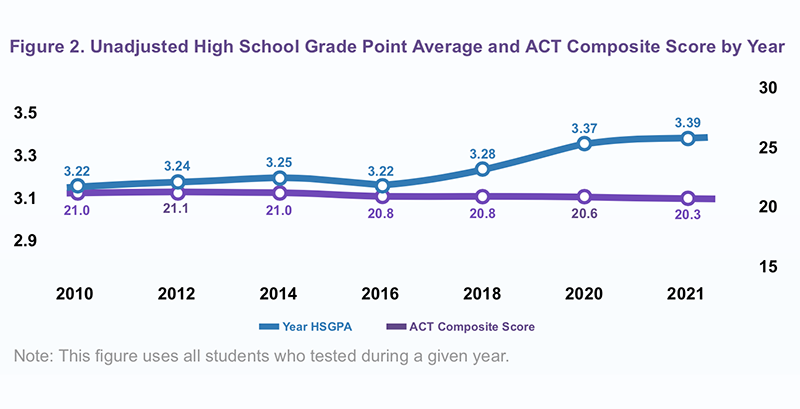

High school grade point averages have been on an uphill climb since 2016. But that doesn’t mean students are better prepared for college-level work. Their scores on the ACT, a college entrance exam taken annually by 1.7 million students, haven’t budged, according to a report released Monday.

Between 2016 and 2021, the average GPA for students taking the test increased from 3.22 to 3.39. But scores on the ACT I — reflecting performance in English, math, reading and science — declined slightly, from 20.8 to 20.3. The trend was especially noticeable among Black students and those from low- to moderate-income homes.

The results, based on a sample of over 4 million students in almost 4,800 schools, reflect “persistent, systemic,” grade inflation, wrote the authors, both researchers at ACT. Following a recent high school transcript study from the National Assessment of Educational Progress — or NAEP — the ACT analysis provides further evidence that grades, which often include points for effort and class participation, don’t reflect objective measures of academic achievement.

The study found more grade inflation in higher-poverty schools. Edgar Sanchez, a lead research scientist at ACT, said it’s unclear why that’s the case and called the study “a starting point.”

But Seth Gershenson, an American University researcher who has studied the issue, attributed the problem to what President George W. Bush called “the soft bigotry of low expectations.” Schools, Gershenson said, award passing grades “and let someone else deal with the lack of learning later on.”

His research also showed growing grade inflation over time in wealthier schools, where “more entitled parents and students” are putting pressure on teachers to give A’s so students can get into top colleges.

It’s unclear to what extent the relaxation of grading standards during the pandemic affected the study’s outcome, wrote the ACT researchers. California students, for example, were allowed to change their lowest grades. And Georgia reduced how much scores on end-of-course tests counted in students’ final grades. The authors noted that students who tested in the middle of a pandemic, especially the spring after schools shut down, “could be different from typical tested students” and also from those who didn’t test until 2021.

At a time when more colleges and universities are making both the ACT and SAT optional for admission, ACT CEO Janet Godwin acknowledged the risk that the paper’s argument in support of standardized testing might seem self-serving,

But she said the company has “a responsibility” to contribute to the conversation.

“We have the means and the data to do this kind of research,” she said.

Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative think tank that has published Gershenson’s work, agreed that ACT has “a big dog in that fight.” Regardless, he agreed that current trends in grading are leaving students less prepared for higher education.

“The heart of the problem is that there aren’t any standards or guidelines for grading in most places,” Petrilli said. “Teachers are on their own, and don’t get much, if any, guidance. Nor do they get much training in [education] schools.”

‘In the dark’

Parents rely on grades to give them an accurate portrait of their children’s performance — especially since they are given more frequently than annual state tests, said Bibb Hubbard, founder and president of Learning Heroes, a nonprofit that helps parents become better informed about their children’s progress.

But many parents might not understand that grades are sometimes more about effort than knowledge, she said.

“When we ask teachers why they don’t share more with parents about student achievement, they report it is fear-based — fear of not being believed, of being blamed and of their principals not having their back,” she said. “The system is designed to keep parents in the dark about their child’s grade-level performance.”

In recent years, some districts have adopted an approach known as “standards-based grading” that educators say offers a more accurate measure of whether students are meeting expectations. It takes the emphasis off non-academic factors like turning in assignments early and attendance — practices that can vary from teacher to teacher.

The 3,000-student Pewaukee School District in Wisconsin, outside Milwaukee, implemented such a model in 2015. Students are graded on a one-to-four system, with one representing below expectations and four indicating advanced performance.

“We didn’t want students’ grades dependent on whether they brought in a box of Kleenex,” said Danielle Bosanec, the district’s chief academic officer. “We wanted kids to stop chasing grades and start chasing learning.”

Parents bought into the plan because it allows students more than one chance at a passing grade on an assignment or test so long as they can demonstrate the additional work they did after their first try. The district agreed to convert final scores into letter grades for transcripts.

Bosanec also conducted her own research to test the connection between the new grading model and ACT scores. In general, she found that in a standards-based model, “as students’ grades go up or down, the impact on ACT scores follows suit.”

Despite the studies pointing to grade inflation, there’s no “widespread evidence that institutions have lost trust in GPAs,” said David Hawkins, chief education and policy officer at the National Association for College Admission Counseling. What colleges crave, he said, is more context.

In the future, he thinks, assignments like research projects or class presentations — used widely in some states like New Hampshire in lieu of tests — could become part of the admissions process.

“There is more to be mined from the student’s high school record than we’re currently getting,” he said. “We’re missing a lot of data about what students can do.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)