Georgia Voters ID Education as No. 1 Issue as Democrats and Republicans Battle to Succeed Reform-Minded Gov. Nathan Deal

Will President Donald Trump’s orange glow reveal the blue heart of a red state?

That’s not science, but it’s the Democrats’ bet in the Georgia governor’s race, which stars two former state legislators named Stacey and a well-funded Republican favorite named Casey. He’s trailed by several restive state GOP veterans and a former Navy SEAL in his first race.

The winner will succeed termed-out Republican Gov. Nathan Deal, whose aggressive policies — notably a failed attempt to gain control over struggling schools — elevated education reform to the center of Georgia politics. A January poll found that voters consider education to be the state’s most important issue.

With the campaign on pace to break spending records, much of the earned media so far has concentrated on Stacey Abrams, a past Democratic minority leader in Georgia’s House whose quest to become the nation’s first black female governor has been embraced by progressives across the country. Her supporters include MoveOn.org, George Soros, and Meryl Streep.

Democrats are energized by the possibility that her strategy — building a grassroots coalition of newly registered voters, marginalized minorities, and the party’s left wing — may be a blueprint for success in states won by Trump in 2016, particularly in the South. They point to the upset win of Democrat Doug Jones over Republican Roy Moore in December’s special election for the U.S. Senate. A higher percentage of blacks voted in that race than in the 2016 presidential election — and 96 percent cast their ballots for Jones.

By contrast, Abrams’s Democratic opponent, Stacey Evans, who is white, has used her hardscrabble upbringing to appeal to moderate voters who have left the party.

The similarity of their views on many issues, including education, has been overshadowed by the competing claims of their campaigns about how Democrats should try to reunify in advance of the 2018 elections. Their disagreement over party identity has surfaced racial and class tensions among some of their defenders.

Abrams led Evans by a 29–17 margin in a Mason-Dixon poll conducted between February 20 and 23, though more than half of likely Democratic voters said they were undecided.

Abrams trailed Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle, now in his third term, by a 45–39 margin. Cagle is considered the favorite: no Democrat has won a statewide seat in Georgia in two decades and, thanks to strong business support, he has raised $6.8 million, more than twice as much as any other candidate. He has run for office in Georgia eight times without losing.

“You don’t have to have a Roy Moore. We have Trump, who’s doing a great job being terrible on things that really affect issues that most Georgians really worry about.”

—DuBose Porter, State Democratic Party Chairman

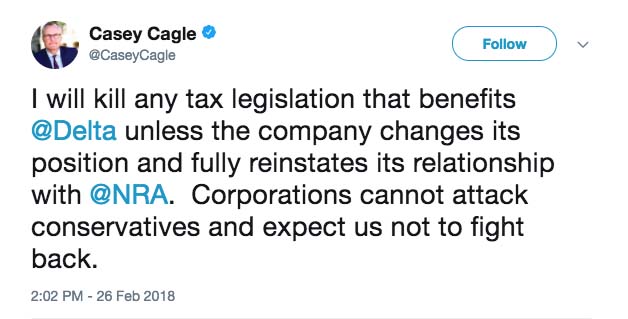

The race may have been shaken up at the end of February, however, after Cagle killed a $38 million tax break benefiting Delta Air Lines, one of the state’s largest private employers, in response to the company’s decision to cut marketing ties with the National Rifle Association following the Parkland school shooting.

The other Republican hopefuls quickly lined up against Delta — one suggested using the money for a July 4 “sales tax holiday” on the purchase of guns and ammunition — but the governor opposed the move. Some fear the pro-NRA backlash against Delta will hurt the state’s chances of landing a new Amazon headquarters in Atlanta, which is on the tech and retail giant’s short list of possible locations.

“For a Democrat to win, it probably would require that the Republican — either the Republican nominee or the Republican Party — do something stupid,” said Charles Bullock, a political scientist at the University of Georgia and longtime commentator on state politics. “It would be more of a vote against the Republican side than the state turning toward the Democrat.”

State Democratic Party Chairman DuBose Porter believes Jones’s win in Alabama provides a road map for Georgia, noting that 65 percent of Alabama’s electorate voted for Trump, compared with 51 percent in Georgia.

“You don’t have to have a Roy Moore,” Porter said, referring to damaging allegations Moore dated underage girls and molested one. “We have Trump, who’s doing a great job being terrible on things that really affect issues that most Georgians really worry about.”

Georgia’s education landscape

Deal has overseen years of economic growth in Georgia, considered by many to be among the best states for business, and the emergence of Atlanta as a destination city. State leaders have wooed Amazon with $1 billion in incentives in return for what Amazon estimates to be a $5 billion project that will create tens of thousands of new jobs.

Deal’s education legacy is less sanguine, but not for lack of trying. The son and husband of schoolteachers, he came into office already believing the state’s sclerotic bureaucracy made it harder for schools to improve.

“Liberals cannot defend leaving a child trapped in a failing school that sentences them to a life in poverty,” he said during his 2015 State of the State address. “Conservatives like me cannot argue that each child in Georgia already has the same opportunity to succeed and compete on his or her own merits.”

Deal helped pass a 2012 constitutional amendment allowing the state to authorize charter schools — Evans voted for it, Abrams didn’t — but was unable to line up support from either minority groups or the small-government right for his signature 2016 proposal: a so-called Opportunity School District for chronically low-performing schools. The schools, which enrolled 68,000 students at that time, Deal said, would be run by the state. Voters rejected the plan by a 60–40 vote; it carried a majority in only seven of the state’s 159 counties.

Evans was one of the few Democrats who supported the district; after Abrams criticized her, she said she regretted the vote and had been frustrated by state inaction, according to a report in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The same report said the head of the Georgia Federation of Teachers believed Abrams hadn’t pushed her caucus to defeat the bill, which passed by one vote, and has endorsed Evans.

Lawmakers passed a much narrower version of state control in 2017 called the First Priority Act: It created a chief transformation officer, reporting to Deal, and gave struggling schools incentives to work with the new office, with sanctions possible over time.

The bill shifted some authority away from the elected state superintendent, adding to tensions that emerged publicly when Deal refused to sign the state’s accountability plan required under the Every Student Succeeds Act, saying that it underemphasized standardized testing. Woods, who prepared the plan, submitted it without Deal’s signature, and federal officials approved it in January.

“It is my hope that Georgia’s next governor will similarly prioritize education and build upon the achievements we have enjoyed these past seven years,” Deal told The 74 in a statement, “as well as the careful and strategic investments and policies we have put into place.”

Student achievement hasn’t moved much. In 2009, the year before he took office, Georgia’s eighth-graders scored at the nationwide average in reading and four points below the nationwide average in math, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Those figures were not significantly different in 2015, the most recent year for which score data are available. (New state tests were implemented in 2015 and don’t yet yield meaningful trends.)

Large achievement gaps on NAEP persisted in 2015, with white eighth-graders outperforming black eighth-graders by 25 points on average in reading and 27 points on average in math. Hispanic students trailed their white peers by 17 points on average in reading and 21 points on average in math.

Mirroring other states, the graduation rate rose from 69.7 percent in 2012 to 80.6 percent in 2017.

Absent more evidence, teacher groups don’t want to see a new governor roil the state with reform laws and initiatives.

“What I’m hearing from the electorate in Georgia is that they’re a little bit burned out on education issues,” said Margaret Ciccarelli, director of legislative affairs with the Professional Association of Georgia Educators.

“We’ve had two constitutional amendments in the past few cycles on education and school reform,” she said. “I think, taking the temperature of the electorate — I haven’t seen any polls to back this up — but I think they’re a little over it at this point.”

The Democrats

Stacey Abrams has a sparkling résumé, even apart from her prolific side hustle as romance novelist Selena Montgomery. Born to a large working-class family, she became high school valedictorian, attended Spelman College and Yale Law School, was appointed deputy city attorney in Atlanta at the age of 29, and led the Democrats in the Georgia House of Representatives by her 30s — the first African American in state history to hold the position.

Stacey Evans’s biography also resonates for many Georgians: The child of a single teenage mother, she describes how she grew up in 16 places by the age of 18 in a well-received campaign video called 16 Homes. CNN commentator Paul Begala retweeted it last year, saying, “This. This. This. This is why I’m a Democrat.”

Evans won a HOPE scholarship and attended the University of Georgia and its law school. After helping litigate a huge Medicare fraud lawsuit that resulted in damages of $495 million, she gave $500,000 to the UGA law school to fund scholarships for those who were first-generation college students.

Evans and Abrams both promote early education, improved social-emotional learning, and increased school funding. Abrams believes quality daycare needs to be part of the solution. Evans supports community schools and better pay for teachers. Both say they oppose vouchers, though Evans initially supported a tax credit bill before voting against it. Abrams has accused her of supporting vouchers, which Evans calls “a lie.”

Their biggest rupture centers on Abrams’s support for 2011 legislation, advanced by Deal, that raised academic eligibility requirements for the HOPE scholarships. Evans argues that poorer students are being hurt, which data bear out. Abrams said she saved the scholarship from further cuts and negotiated added benefits.

Abrams plans to depict Evans as more conservative than she seems, according to a strategy plan she shared with supporters. The strategy veers close to fault lines that emerged when Abrams’s backers protested Evans last summer as she delivered a speech by chanting and holding signs that said “Trust Black Women” and “Evans=DeVos,” a reference to billionaire Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who is deeply unpopular among Democrats.

Abrams has raised $2.3 million, including donations from every state and most of Georgia, but she has also spent all but $460,000 on a far-flung grassroots operation. Evans has also received $2.3 million, about half of it lent to herself, but she has $1 million more on hand than Abrams.

The Republicans

Like Evans, Casey Cagle was born to a single mother. He dropped out of college — buying a tuxedo rental shop — but was elected to the state Senate at the age of 28. He is considered a moderate and doesn’t bring up President Trump, whose approval rating in the state dropped to 37 percent in January. (Among Georgia voters who voted for the president, 85 percent say they approve of his first year in office.)

A plurality of voters also told pollsters that improving education was the most important issue facing the state, followed by health care.

Cagle wrote a 160-page book, Education Unleashed, blurbed by former U.S. secretary of education William Bennett, that functions as a campaign manifesto. He decries “the compliance mentality of our state’s educational bureaucracy” and calls for empowering local districts, even allowing them to design their own assessments. He champions charter school and voucher expansion and prep programs that prepare students for study at one of Georgia’s 22 technical colleges.

A Cagle administration would likely hew to Deal’s choice-friendly reforms but direct more resources to postgraduate readiness and devolve autonomy to districts rather than consolidate an oversight presence in Atlanta. Like Abrams and possibly Evans, he would push back on the state’s testing regime.

A February Mason-Dixon poll showed Cagle to be far ahead but also indicated that he may face a primary runoff because of the crowded field. Several of his GOP opponents have run ads using impersonators that make Cagle look inept. Their effectiveness isn’t clear, but there’s plenty of money to spend. Secretary of State Brian Kemp has raised $2.9 million. Trailing are Hunter Hill, an education-reform-friendly Army ranger and former state senator with $2.2 million; and Michael Williams, a pro-Trump legislator whose appearances have attracted supporters of the president. like reality TV star Duane “Dog” Chapman and longtime Trump adviser and friend Roger Stone.

Clay Tippins, a little-known businessman, served as a Navy SEAL in Iraq, according to his campaign biography. He earned staying power by raising $2.1 million (some of it lent to himself) and increased his Q score by running an ad in Georgia markets during the Super Bowl.

The candidates have amassed a total of $19.4 million, compared with $13.3 million at this point in the last open governor’s race in 2010, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The primary is May 22.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)