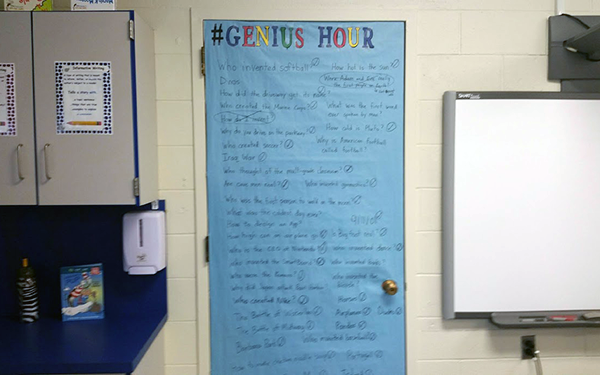

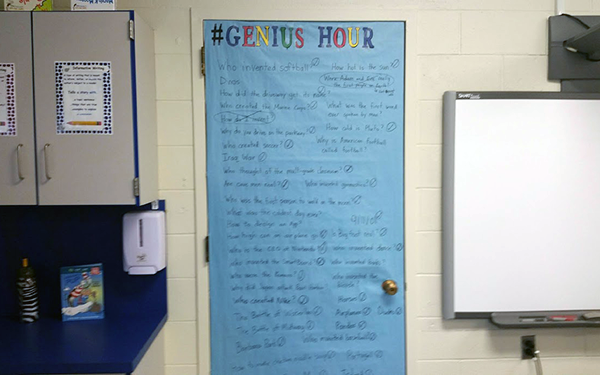

An open canvas plastered with bright blue poster paper lined the back door of Mr. Mark Maglione’s classroom at Lillian Drive Elementary School in Hazlet, New Jersey, as the multigrade teacher began the school’s first-ever “Genius Hour” last September. “In a perfect world, if you could study anything you wanted in school, what would it be?” he asked the gathered anxious third- and fourth-graders on that Friday afternoon.

Maglione recalls that the small hands started raising slowly, and then all at once, as the kids erupted with a diverse mix of responses, his students’ enthusiasm growing louder and more specific. Like all great geniuses, their ideas knew no bounds, ranging from how to build a model World War II fighter plane to using a swivel camera to record a presentation on their Chromebooks.

Maglione marked down the ideas on the bright blue canvas.

That poster became known around school as the “Genius Hour Door,” a free space where ideas both big and small – some that only an unclouded 9-year-old mind could conjure, like “what was the first word ever spoken by man” and “how cold is Pluto?” — were not just welcome but encouraged. And Maglione says it did more than just facilitate a brainstorm; it helped him connect with, engage, and activate his students.

In an interview with The 74, Maglione explained that Genius Hour became a new conduit through which he could get to know his students and discover their interests without doing a formal assessment. Later, after students had had time to work on their passion projects independently or as part of a group, they presented those ideas to the class. “It’s sort of like show and tell on steroids,” he recalls.

Lillian Drive Elementary is just the tip of the iceberg. Genius Hour can now be found in classrooms across the country — as an initiative that encourages students to spend one hour per week exploring their passions and creativity. The name, by most accounts, derives from Google’s “20 percent rule,” a company initiative that guides employees to spend 20% of their time working on something other than what’s in their official job description.

At Google, the 20 Percent Rule has

inspired two of the company’s most popular products — Gmail and Google News — and in a 2004

founders’ letter to investors, Larry Page and Sergey Brin credited the 20 Percent Rule with baking creativity into the very DNA of the company: “Google employees have ‘20 percent time’ — effectively one day per week — in which they are free to pursue projects they are passionate about and think will benefit Google. The results of this creative effort include products…which might otherwise have taken an entire start-up company to create and launch.”

Although there’s no exact way to know how many classrooms have embraced Genius Hour, it’s clear that it’s happening everywhere from rural Texas to larger cities in Illinois and New Jersey. The 74 spoke with educators in each of those states, and they all started down the path much like Mr. Maglione did — with an art project aimed at bringing their students passions, curiosity and multiple intelligences to the surface.

Allison LaFalce, a fourth-grade teacher at Komensky Elementary School in Berwyn, Illinois, asked her students to write down all the things that make them “wonder,” or the things that they were concerned about, and then used those ideas as a catalyst to contribute to a

school fundraiser to build a new inclusive playground for students with special needs. “I want my kids to think ‘How can I share this with the world, would it make a difference, and would it help other people?’,” she told The 74.

Students expressed interest in learning how candy was made during one such Genius Hour, and decided to conduct a pseudo-science experiment, and then sell homemade candy at the school’s first ever Genius Hour Showcase a week ago. All proceeds from that sale are now going towards the playground for students with special needs.

Genius Hour looks different from classroom to classroom — and perhaps that’s the point. LaFalce says the main motivation for starting this program at her school was to unlock the unique inner genius in each of her students: “Our belief is that everyone has some type of genius, whether it’s academic, fine arts, public speaking or athletics, and something to offer the world.” An added bonus: LaFalce says that her school’s Genius Hour events have sparked new involvement from her community’s parents.

1,000 miles southwest in Waco, Texas, instructional coach Jessica Torres of Lake Air Montessori Magnet School explains that Genius Hour has helped her identify gifted students who perhaps did not test well, but who have inner talents that only became evident during that one hour a week. “Originally we were struggling to service gifted and talented students, but Genius Hour allows us to help bring up students that have the possibility of being gifted and talented,” she says, “but you never realized it because they weren’t being given the opportunity to showcase their true talents.”

While there isn’t currently any quantitative data that links Genius Hour to higher overall test scores, Torres is adamant that she’s watched her Genius Hour participants become better problem solvers, learning week to week how to ask the right questions, increasingly taking more initiative and exhibiting greater independence.

Due to the success of her Genius Hour pilot, Torres is now creating a professional development model that will allow teachers at her school to have similar breaks for creative thinking. “If teachers are given more time for their own creativity to come out,” she explains, then “we would see better things happening in the classroom.”

While the term “Genius Hour” evokes images of free-wheeling independent study, many teachers involved in these kinds of programs insist that it works best if there’s some degree of structure and accountability — as well as a clear end goal to work towards.

Maglione, the teacher from New Jersey, said that in order for Genius Hour to be successful, he felt that teachers needed to keep an open mind, allowing for flexibility and students’ self direction. He also said that his students’ overall enthusiasm had noticeably increased, and that they were learning many research and presentation skills during their Genius Hour sessions that had not previously been taught at their grade levels.

“In college, people start to ask you that question: ‘What do you want to do with your life, what are you interested in?,’” Mr. Maglione says, “but often times we fail to ask students that at a younger age.”

Other teachers agree that Genius Hour has fostered an entrepreneurial spirit among their students, and many have said that it’s now their favorite part of the week. Parents, likewise, have also expressed approval, saying that their kids come home energized and excited, eager to take ownership over their own education.

“We love growing our students, so by the time they reach 8th grade, they are their own advocates,” Torres explained. “They are confident about who they are and what they can do.”

;)