Gathering Better Data on Latino Students Is Key to Truly Meeting Their Needs

Castillo: 'Latinos' are not one big group of similar-looking people with similar experiences. Student data needs to reflect that

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

I’m embarrassed that as a brown-skinned, Mexican-American Latina, I didn’t know Afro-Latinos existed until I went to college and personally met them. Growing up in a homogenous, predominantly Mexican community did not allow me the opportunity to interact with diverse groups of Latino or other racial/ethnic groups. This unfamiliarity was compounded by my local public school education, which did not offer ethnic studies or any course on Latino history in the U.S. I was ignorant of the diversity and complexity of my own culture.

Even today, the American media, Latin American media and many others talk about “Latino” individuals as if we were one big group of similar-looking people with similar experiences.

However, we have a variety of distinct national origins, regional cultures, languages, skin colors and immigration statuses. Unless governments and organizations begin to collect this data, the public will remain unaware of the differences within the Latino community — and more importantly, the lack of nuanced and granular data prevents schools and community-based organizations from assessing students’ unmet needs or redirecting and improving services to all student ethnic subpopulations.

Government numbers drive policy and funding in social services. There are 62 million Latino individuals in the U.S., and 13.8 million Latino students in K-12. Of those, about 1 million are Latin American-born. It wasn’t until 1970 that Hispanic individuals were officially counted in the U.S. Census. Before then, they were simply classified as “white.” The 2000 Census marked the first-time individuals were allowed to select their race and ethnicity rather than have census workers fill in the form during a home visit based on their own individual biases and assumptions. Researchers recommended that the 2020 Census merge the race and ethnicity question to increase the accuracy of estimating the Hispanic population. But the Trump administration rejected that suggestion. And due to to pressures from the administration to end data collection early and exclude vulnerable undocumented populations, as well as the difficulties of capturing accurate data during the pandemic, Hispanics were undercounted by 5%.

Simply collecting the number of Hispanics is not enough. Many Latino Americans prefer to identify with their country of origin over “Latino,” “Latinx” or “Hispanic” because it is more representative of their culture (i.e. Colombian, Salvadoran). There are also great complexities and inequities within the Latino student population:

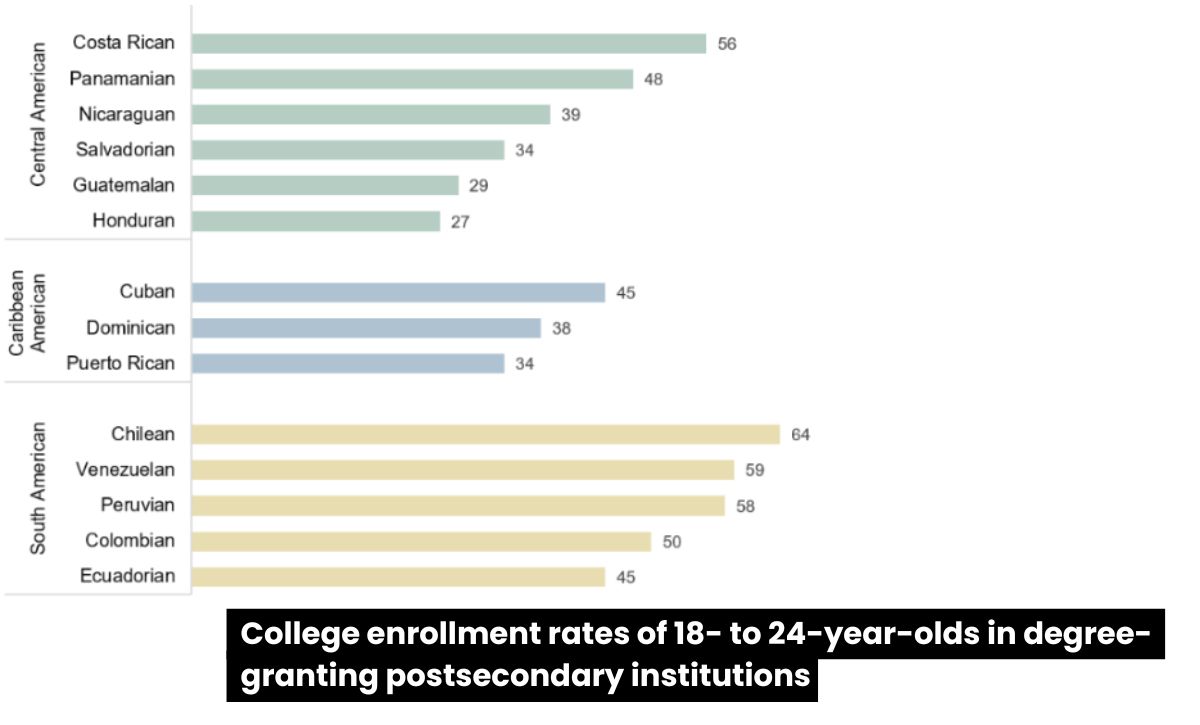

Average college enrollment rates of 18- to 24-year-olds in degree-granting postsecondary institutions by selected Hispanic subgroups

Data are based on sample surveys of the entire population in the given age range residing within the United States. Although rounded numbers are displayed, the figures are based on unrounded estimates. SOURCE: U.S. Department of Commerce, Census Bureau, American Community Survey (ACS), 2016. See Digest of Education Statistics 2017, table 302.62.

Differences in enrollment rates for Central American and Caribbean students compared with students from South American countries highlight the glaring inequities within the Latino community. These differences also point to some of the ways that students’ particular immigration stories might influence their educational trajectories (e.g., when did students arrive in the United States, and under what circumstances?). Taking this analysis a step further would mean collecting data on Latino students who identify as Afro-Latinos and examining racial disparities.

To do this, federal, state, and local governments as well as youth-serving organizations should begin to collect more detailed demographic data beyond Latino versus non-Latino. However, this could well be complicated by the tension that exists between the benefits of having more complete information about student backgrounds and the very real risks that undocumented families face. With proper data privacy protections in place, I and other researchers recommend the following:

- Collect data on country of origin, as is being done for students in Washington State and Portland Public Schools.

- Collect data on Afro-Latino, and Indigenous tribal affiliations

- Ask students about formal schooling in their country of origin

- Include language options other than Spanish, particularly Indigenous languages that may be relevant to the population served

- Collect data on recency of immigration (Are the students first- or second-generation? How long have they been in the U.S.?)

This information can inform specific policies and practices that might improve schooling for Latino students, including those related to hiring and training staff, implementing culturally responsive education and implementing ethnic studies. Public schools must not only meet the needs of Latino students by collecting better data, but educate them on their rich history.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)