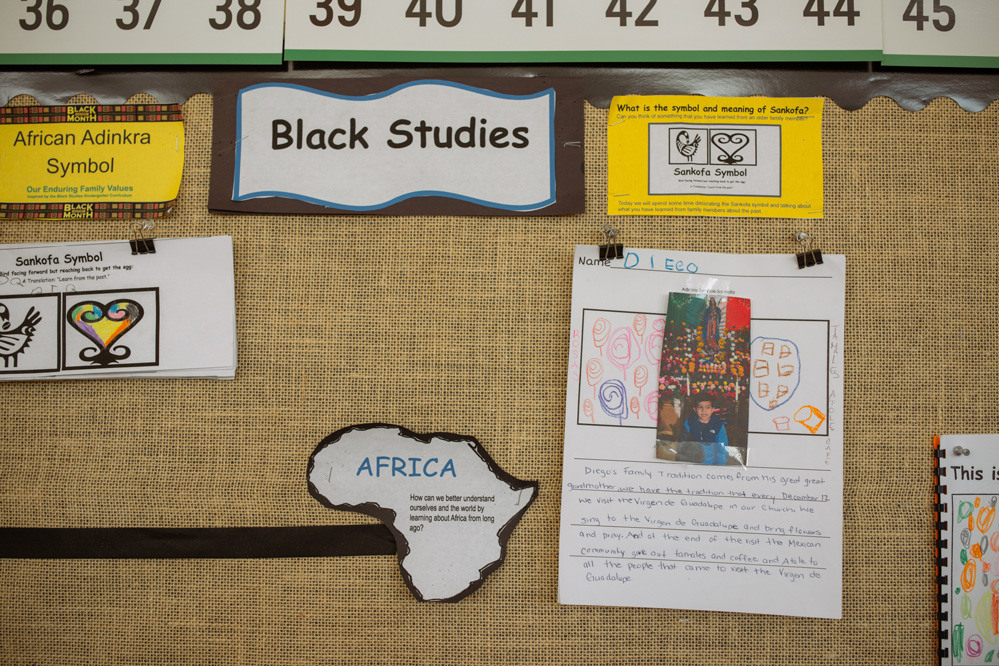

The culture of change trickles down into small decisions, like ensuring the skintones of cartoon hands to use for classroom posters used for counting or storytelling aren’t always white by default.

And at the end of each lesson plan in the city’s curriculum, a question prompts educators to reflect on their own biases: “how will you maintain high expectations for all students?”

Through monthly professional development sessions at their school and separate offerings through BERC, educators like Sera and kindergarten teachers Michelle Allen have become more confident in both the subject matter and how to facilitate the classroom conversations in ways that are developmentally appropriate.