Funding Crisis, Charter War, Teacher Shortage: Who Wants to be WA. State Schools Chief? These Five.

The 74’s Carolyn Phenicie examines local and state level elections where education will play a critical role this November.

The next superintendent of public instruction in Washington state will not have an easy job.

Education leaders in all states will have new authority over schools under the just-passed rewrite of No Child Left Behind. In Washington, that’s likely to include testing, a hot-button issue in a state where entire junior classes in some high schools walked out to protest SmarterBalanced tests last year.

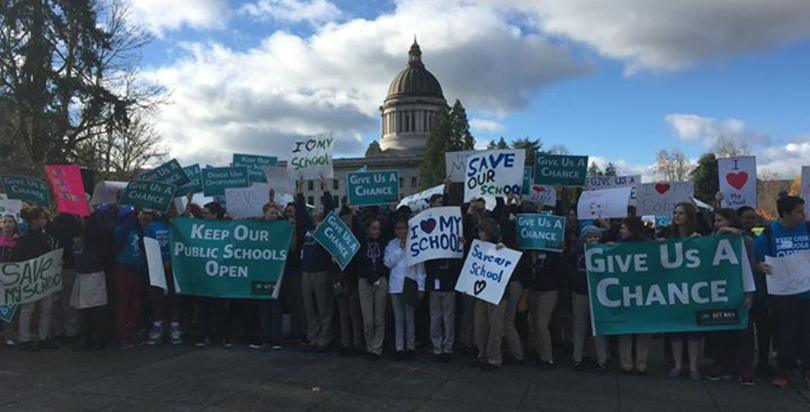

Washington state legislators are currently being fined a $100,000 a day by the Supreme Court for failing to fully fund education. Those same legislators are in a pitched battle over whether, and how, to save charter schools, deemed unconstitutional by that same court. Add to that a teacher shortage that many say is verging on a crisis. (Read The Seventy Four’s complete coverage of the Washington state charter school decision here.)

Yet those challenges have not stopped five people from stepping up to try and replace outgoing state schools Superintendent Randy Dorn, who is not seeking reelection in November. The roughly $122,000-a-year job is officially nonpartisan and carries a four-year term. Washington is one of only 13 states that elects its highest K-12 schools official.

All five contender spoke with The 74 recently. Here is a rundown of who they are and where they stand on the major issues.

The candidates

Robin Fleming

Age: 55

Administrator for health programs, state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction

Hometown: Seattle

Age: 55

Administrator for health programs, state Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction

Hometown: Seattle

Fleming grew up with a single mother who struggled to care for her brother, who had Down’s Syndrome. At the time, individuals with disabilities had few rights, and Fleming’s brother was institutionalized. She also lost a good friend who had AIDS to suicide. It was those experiences, she says, that spurred her to leave a decade-long career in journalism to become a nurse.

She started in a hospital trauma center before spending 13 years as a nurse in the Seattle Public Schools where, she says, she saw it all, from students who overdosed on drugs in the school bathroom to children with gunshot wounds.

Eventually she went back to school again and got a doctorate in educational health and leadership. Her thesis broke down data on school nurses visits and found that the “vast majority” of middle and high school students in Seattle going to see the school nurse came from poverty. “These kids are not well and they are not achieving in school,” she says. The work that school nurses do “get kids to school, keep them at school and help them engage at school and graduate from school.”

Fleming is currently the health services program administrator at the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. She administers a statewide program that ensures access to school nurses, as well as one that helps kids who are out of school temporarily due to illness.

She says friends had encouraged her to run for office in the past but she never found a position in which she felt she could make a difference. Now, she says, she has something to offer that no one else in the race can.

“I knew I could do more for our state’s children, that’s what sort of lit me up.”

Erin Jones

Age: 44

Tacoma Public Schools administrator

Hometown: Tacoma

Age: 44

Tacoma Public Schools administrator

Hometown: Tacoma

Jones, whose birth parents were a younger white mother and older black father, was adopted by two white teachers from Minnesota. When Jones was young, her family moved to Europe to find a more welcoming environment for a biracial family. Her father got a teaching job at the American School of the Hague, and she grew up in a diverse environment with the children of ambassadors from around the world.

Jones returned to the U.S. for college, at Bryn Mawr College, an all-women’s school just outside of Philadelphia. In the years since, she and her husband have lived all over — Indiana, Ohio, and ultimately Washington, where her husband grew up. She’s also had a variety of careers, including stints operating a school from her garage and playing on the U.S. national women’s basketball team.

In the education realm, she’s been a substitute and taught English and French immersion. She also served in the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction for two-and- a-half years for previous state superintendents.

Now her official title is director of AVID (Advancement via Individual Determination, a program designed to support first-generation college students as early as kindergarten). In reality, she says, she does a lot more than that: She’s expanded the AVID program so every middle school student has the skills necessary for success in college.

She also does a lot of teacher training and often deals with legislators, given her experience in the state office.

“I’m running because I believe our students deserve better, and I’m running because I want to be a voice of collaboration between many groups of people,” she says.

Gil Mendoza

Age: 61

Deputy superintendent for K-12 programs, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction

Hometown: Tacoma

Age: 61

Deputy superintendent for K-12 programs, Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction

Hometown: Tacoma

Mendoza’s parents were migrant workers before his father joined the military; he grew up mainly in Tacoma. He graduated from Gonzaga University in Spokane with a degree in psychology and credentials to teach social studies and a special education.

He’d attended college on an ROTC scholarship, then served six years in the military, four on active duty and two in the reserves.

He moved out of state for better employment prospects after leaving the military and wound up working for billionaire and 1992 presidential candidate Ross Perot in Dallas doing human resources and corporate recruiting.

Mendoza was back home in Washington state by the early ’80s and worked “at every level” in the K-12 system. He’s worked in schools since 1983 with the exception of three years he helped launch a technical college. Mendoza was a career counselor and teacher, then moved into administration in the Tacoma schools for 13 years after earning his doctorate. He also served four years as superintendent in the Sumner schools, in suburban Tacoma.

Eventually he came to work for Dorn, the current superintendent, serving first as a special assistant and leadership coach within the agency and eventually moving into his role as K-12 assistant superintendent.

He entered the race after looking at the candidates who had filed and thought “we needed someone who had a more in-depth background in education in Washington state.”

Chris Reykdal

Age: 43

State legislator

Hometown: Tumwater

Age: 43

State legislator

Hometown: Tumwater

Reykdal is one of eight children who grew up in poverty in Snohomish, Washington. It was public school, he says, that gave him the opportunity to break out of that cycle.

He went to Washington State University in Pullman and earned degrees in social studies, along with his teaching certificate, and taught history in Longview, Washington, for three years.

Then Reykdal and his wife headed to Chapel Hill, where he earned a graduate degree at the University of North Carolina in public administration. They returned to Washington, where Reykdal worked for the state Senate, and made his way up the ranks of the state board that oversees community and technical colleges. He’s currently the associate director of the education division there, where he helps direct policy and appropriations for the state’s 30 community college districts. He also served four years on the Tumwater school board.

Reykdal, a Democrat, was elected to the state house in 2010. He’s currently the vice chair of the House education committee. He says he’s most proud of “rescuing” a bill that will require students starting with class of 2019 to pass 24 specific credits, including three science classes, to graduate from high school. The bill ultimately means kids in Washington will take more math and science, he said.

Reykdal said his passion for public service comes from the benefits government programs gave him and his family when they were struggling.

“Now there’s this enormous opportunity to take our state office that is constitutionally charged with overseeing education in our state and really reimagine its focus.”

Larry Seaquist

Age: 77

U.S. Navy veteran, former state legislator

Hometown: Gig Harbor

Age: 77

U.S. Navy veteran, former state legislator

Hometown: Gig Harbor

Seaquist spent most of his career in the military. The 32-year Naval veteran served as a warship captain and in budget and national security functions at the Pentagon.

He eventually wound up in Washington state and was elected to the state House in 2006 as a Democrat. He served four terms, including stints on committees covering early learning, education and budgets. He chaired the House higher education committee.

Over that eight years, he became “increasingly concerned” about the state’s “failure to invest in our education system,” he says.

The problem has two parts, he says, starting with cutting education funding to balance the state budget.

“I was able to stop that and get those investments re-started, but along the way we were also installing and inflicting, quote, reforms, on our K-12 system,” he said.

Seaquist says he wants to use his campaign to push specific legislative issues, like the Supreme Court’s funding ruling.

“We’ve been locked up in legislative battles that haven’t changed in several years, and I don’t believe that we can simply sit around and let those wars wage in the same old trenches for another year.”

Where they stand

On school funding equity

Fleming: The legislature does need to fully fund education, and agrees with the current superintendent’s comments on the issue, though thinks legislators should be motivated with honey, not vinegar.

Doesn’t offer any specifics regarding how the legislature should find the new money to meet its court obligations. “We have to have revenue somehow, and that’s the legislature’s job to come up with that.”

Jones: Was working for the state superintendent’s office at the time the Supreme Court heard the case, known as McCleary, and testified in her capacity as an educator. “It’s really become something that’s bigger than I ever thought it was going to be at the time.”

The legislature has just kept pushing back deadlines, to the detriment of children.

Lawmakers should not impose new mandates before they fully fund the ones they’ve already written. To pay for it all, legislators should close tax loopholes, including ones given to ensure Boeing, the state’s largest private employer, retains thousands of jobs in the Puget Sound area.

“I understand it’s a capitalist society, free market, whatever, but we’ve got to serve our kids so we’ve got to do the things that create equity.”

Mendoza: Doesn’t think the legislature will meet the 2018 deadline the court imposed, sees 2021 as a more realistic benchmark.

The money that the legislature has put toward meeting the court’s demands hasn’t been appropriately delineated. They’ve met requirements for funding materials, supplies and operating costs but failed to include language requiring districts to use that money for its intended purpose.

The legislature should address the local property tax system that has given rise to widely disparate teacher salaries across the state. Also backs a tax on capital gains for the wealthiest Washingtonians.

The real issue is that increases in school spending haven’t kept pace with increased spending in other areas of state government. Doesn’t, however, support cutting those other services to fund K-12.

“It is not appropriate to decimate other services that are not basic education that serve our families,” like higher education or state health and welfare programs. “We would be creating bigger problems than we have now.”

Reykdal: A budget guy at heart, thinks it’s important to understand the scope of the problem. The legislature has put in an additional $3.5 billion over two years. To come up with the other $2 to $2.5 billion the court requires, lawmakers would have to increase taxes 8 to 9 percent or cut other state services by 14 or 15 percent.

Democrats, who control the state House, can’t raise taxes enough to cover the shortfall without losing their majority, nor can Republicans cut services enough without risking their majority in the state Senate. “The political side to this thing is enormous.”

Proposes taxing capital gains, an idea pushed by Democrats. That would close about a third of the gap. Agrees with Republicans’ proposed “levy swap,” switching from a local property tax system to a statewide one. That would cover about another third. “I can get about two-thirds of the way there in a bipartisan way, and after that it is really, really difficult.”

Seaquist: Even more important than meeting the court-imposed deadline is making a difference for the millions more students who will go through an inadequately funded school system every year the legislature doesn’t act.

The next step should be putting school district leaders on a task force so they can figure out what’s really needed for basic education expenses and how best to get that money from the state.

“If they can’t do it, I will try to make my campaign a good government campaign in which we’re addressing those issues, we’re consulting with people, we’re not just running a vote-for-me-campaign, we’re running a campaign on substance that is consulting with the public and with educators on these kinds of issues.”

On charter schools

Fleming: Strong advocate for innovation in education, but believes that can be done by “keeping public money where public money belongs and is adequately monitored.” It’s not fair that not every student has the opportunity to attend an innovative charter.

Recently read “The Prize,” the story of efforts to turnaround schools in Newark, New Jersey, and took it as a cautionary tale. “The jury is out. Some charter schools do great and others don’t do well at all. I don’t think this is a time we can experiment with our kids.” (Read a defense of Newark’s reform efforts from a charter school educator here.)

Jones: Voted against the 2012 initiative that allowed charter schools, though is not opposed to innovation.

“My first response was not that I inherently don’t like the idea of innovation, but if we’re not funding what already exists, how can we responsibly take on this big financial responsibility of charter schools?”

Also doesn’t believe that charters spur traditional public schools to greater innovation.

Mendoza: Charter schools were created to offer “innovative opportunities for learning” outside the traditional school system. “I would posit that we have the potential and the ability to offer that in public education.” The Tacoma School for the Arts, for example, offers an arts-based curriculum with close ties to the city’s arts community and is run by a board of directors that has district backing.

There were two bills before the state legislature aimed at keeping the schools open while complying with the court’s ruling. The superintendent’s office, and Mendoza personally, backed one that would bring the charters under the authority of their local districts. That bill did not make it out of committee.

The other bill that did and was passed by the full Senate leaves charters under a statewide authorizer but funds them through an account that draws from the state lottery. Mendoza doesn’t care how the schools are funded so long as they’re overseen by local school boards.

Reykdal: The state Supreme Court’s decision was the right one, and there isn’t a way to have a statewide authorizer that isn’t also connected to local districts.

At a minimum, local districts should be “back in the driver’s seat as authorizers.” Even if that’s possible, is “not there yet” on the idea of charters.

“I support absolutely innovative schools, even contracted-out services, as long as local school districts authorize them and have accountability.” And that isn’t what he would call a charter school.

Seaquist: Also voted against the charter initiative. “My view is that there is plenty of creativity in the public schools”; should be more focus on what he calls “liberating learning.” Is concerned though about the 1,100 charter school children whose schools are in jeopardy. Waiting to see what solution the state legislature crafts and whether it passes constitutional muster.

On the teacher shortage

Fleming: Given all the pressures put on teachers in terms of expectations and accountability, the educational requirements and relatively low salary, “it’s no surprise there’s not a lot of people lining up” to be educators. It’s important to make teaching a valued profession.

Would work with the state’s higher education leaders, as well as with high schools, to develop a career pathway for teenagers interested in a teaching career.

Concerned not only with having sufficient teachers, but having a diverse educator workforce. “This is a very urgent time,” given that, by 2025, white children will be about 40 percent of the student population.

Jones: “We’re in crisis, and not just in the rural areas.” In her district, about half the teaching workforce is at retirement age.

The state should work to find ways to get people who already have degrees and experience in other areas to get the necessary instructional training in a year. The state should also help fund that training. Why would someone take out a $20,000 loan to earn a salary of just $35,000 a year?

And the state needs to create incentives to get teachers to rural areas, specifically new housing options and perhaps expanding loan forgiveness programs already available to teachers in urban areas to those who teach in the most remote parts of the state.

Mendoza: Deals with the issue firsthand: his office approves the emergency substitute designations that let districts fill spots last-minute with people who don’t have any kind of teaching or other educational credentials. In 2013, the office approved 1,500. The next year, it was 4,000. Predicts the problem will only get worse as teachers who would’ve retired in the last few years but were hampered by the worsening economy are now in a position financially to do so.

Pay is also an issue. Teachers are underpaid, particularly at the entry level. Would like to change state laws so that retired teachers can spend more time as substitutes. Would also like to change the rules to allow people from other states to more easily transfer their teaching credentials to Washington.

Reykdal: Puts the blame on the backs of the state legislature. In an attempt to save money, lawmakers prohibited state employees, including teachers, from taking another public-sector job after retirement. This was meant as a way to prevent people from double-dipping a state pension and salary at the same time, but has led to a big drop in the number of available substitutes.

To get more people into the classroom full time, the state needs to offer more incentives. Backs the governor’s proposal to raise the starting salary to $40,000 a year, and the state should restore professional development, which has been “cut to the bone.”

Seaquist: “The teacher shortage to me is reflecting that we have been mismanaging our schools.”

Not only concerned about the lack of new teachers entering the profession and long-term educators leaving it, but mid-career teachers who exit the classroom after working between five and 15 years.

Given his military experience, he’s interested in better managing corps of educators, making sure there’s better professional and career development for them. Also concerned about the diversity in the teaching ranks.

On testing

Fleming: Standardized tests do have a role in education, but there are many ways students can prove that they’ve learned what they’ve been taught. Would work with others around the state to find other ways to evaluate students, like portfolios or thesis projects.

Not opposed to tests as a small portion of teacher evaluations, but they shouldn't be used on their own. “That is patently unfair. It’s the same as evaluating a doctor because she didn’t cure cancer. You just can’t do that.”

Jones: Pleased the new federal K-12 law offers new flexibility on testing as well as a cap on testing time. In her district, students are tested six weeks a year, calls that “criminal.”

Also skeptical about the role of student test scores in teacher evaluations.

“I totally believe in holding teachers accountable, and I believe in teacher evaluations, but I really am challenged by this idea that a test can measure how a teacher is teaching.”

Also doesn’t think it’s fair, given how many teachers instruct in subjects that aren’t tested.

Mendoza: Tests are “critically important.” “I think districts who complain about too much testing, we only require one test as a state. Too much testing means they’re doing other tests.” Doesn’t think though that passing any single test should be a requirement for graduation.

Believes the juniors’ walkout on the SmarterBalanced test last year was because they didn’t see its value. The students had already passed all their tests needed for graduation, and weren’t aware that most colleges in Washington have agreed to use SmarterBalanced test results for college course placement.

“We think it will clean itself up as time goes on” as students realize the test’s value to learn more about themselves.

Doesn’t support tying test scores to teacher evaluations, at least in the way it’s often done. Instead, thinks teachers and principals should use the information gleaned from the tests as jumping off points for teachers’ goals. In short, it should be how teachers respond to the scores, not the scores themselves.

Reykdal: There’s been a lot of rhetoric around SmarterBalanced in Washington, but they’re ultimately good because they’re aligned with the Common Core. There are, though, too many tests. The state should stick with SmarterBalanced and “get rid of pretty much everything else.”

All states are going to have to challenge the “last great hypocrisy” in the Every Student Succeeds Act that grants an affirmative right to opt out of tests but requires states and districts to maintain a 95 percent participation rate. Thinks states could perhaps count Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, SAT or ACT exams to hit the 95 percent target.

Thinks the examples from other states makes clear that test scores shouldn’t be tied to teacher evaluations. “I think the research is clear we’re not there yet. Maybe someday we’ll find the algorithm that works better,” he says.

Seaquist: Is highly skeptical of standardized tests, at least as they’re currently given. Disappointed the No Child Left Behind rewrite continues “high-stakes federal tests.”

“My view is that this high-stakes testing regime has actually ended up sorting out our low-income, minority students with increasing efficiency. The reason why we have an equity gap is not only because the economy is leaving more and more of our families and kids behind, it’s because our school system is sorting kids with more efficiency.”

Thinks standardized tests should be given more like the National Assessment of Educational Progress (better known as NAEP), which tests a sampling of students, rather than all of them.

Also doesn’t back tying evaluations to test scores, and played a role in blocking efforts to tie the two together. That failure eventually resulted in the state losing its No Child Left Behind waiver, which was “a bit controversial, but was the right thing to do.”

On alliances, education reform and unions

Fleming: When most people say education reform, they mean charters, but that’s not the true definition of reform. “I’m for changing things for the better, and I think we have a wonderful opportunity to do that,” with the new federal education law. Specifically, would like to make education innovative and empower teachers.

Was a union member during her 13 years as a school nurse. “I strongly support unions and the right of people to bargain collectively for their benefits and salaries.”

Jones: Is running as a true non-partisan, and has tried her whole career to bring divergent views together. Gotten along well with education reform groups, and has friends in the union. Secretary is a leader in the classified employees’ union.

Union leadership isn’t universally a fan, though. “The teachers union, however, I’ve not always gotten along with, and they haven’t always liked me.” Is “a supporter of great teaching and great teachers,” and “the union can be about issues that are not related to great teaching.”

Mendoza: On the question of aligning more with education reformers or unions, is a little bit of both: “I believe in reform, but I don’t believe in throwing the baby out with the bathwater.”

Mostly fed up with those who villainize teachers, one of the most important factors in a child’s future. “I’m not pro-union as a concept, but I’m totally pro-teacher. I’m tired of our system, our state, our pundits, not only undervaluing, but demonizing teachers.”

Reykdal: Doesn’t align more with a pro-union or pro-reform camp, though thinks the race could “devolve to that.”

There’s something for candidates to like and not like with unions, who have supported the Common Core Standards but have been “very aggressive” about trying to de-link exams from evaluations. There’s also something to like and not like about business-aligned reform groups, which have been “pretty darn good about trying to fully fund our schools” but also focused on keeping standardized exams.

“It’ll be very interesting to see how this shakes out.”

(The state’s chapter of the American Federation of Teachers gave Reykdal the $950 maximum donation in the 2014 primary; the Washington Education Association gave the maximum in both the primary and general election, for $1,900 total.)

Seaquist: “My stance is pro-teacher, pro-educator.” It’s important to “liberate learning” and the state should do more to support teachers. In traveling around the state, hasn’t seen “these bad teachers” that some talk about. Has areas of disagreement with the union.

(Both statewide teachers unions contributed the $1,900 maximum amount to Seaquist for both the 2014 primary and general elections. So did a political action committee affiliated with the League of Education Voters, a business-backed group focused on equitable school funding. He lost the general election that year.)

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)