From Teachers to Nurses, NYC Has ‘Bent the Arc’ of Union Health Care Costs — but Was It Sacrifice or Good Timing?

This is how the stars aligned above New York City: A mayor loathed by organized labor ended his time in office. His successor governed as a friend to workers. The city’s new negotiator arrived with social capital from his years as a union strategist, and — fortuitously — the growth of insurance costs slowed, creating a huge windfall for the city.

These were the right-time-and-place elements, converging in the spring of 2014, that allowed New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio to reach a relatively little-watched but massive four-year agreement with union leaders to cut health care costs by $3.4 billion. The deal, which must hit its final savings benchmark in 2018, affects city workers and their families — nearly 1 million people, the city says.

For a workforce that had gone without raises for three years or longer under Michael Bloomberg, de Blasio’s term-limited predecessor, the package helped the city afford new contracts that included back pay and raises while continuing to spare union members from having to cover any of their health insurance premiums. (New York remains the only large American city where this is true.)

“We had an opportunity to completely change the nature of the relationship and to say that we are not here to simply tell you how we have to get these savings,” Robert Linn, the city’s energetic labor relations commissioner, said in an interview. “We’re here to create a process where we work together to do it.”

To de Blasio, New York City achieved the urgent and difficult task faced by government and the private sector everywhere: It “bent the arc” of health care costs downward, he said.

But budget watchdogs demurred; “some of the largest items have little to do with the current and future behavior and health of city workers,” said George Sweeting, deputy director of the Independent Budget Office, during a February 2016 city council hearing. He cited gains attributed to the agreement that were the result of unrelated trends that slowed insurance cost growth below city projections.

Over the course of the agreement, according to Linn’s office, $1.9 billion of the $3.4 billion in targeted savings, or about 56 percent, will come from lower-than-expected premium costs.

“It’s like taking credit for the sun coming up in the morning,” said Charles Brecher, senior adviser for health policy at the Citizens Budget Commission. The group argued that savings due to “economic trends,” rather than “actual results of specific initiatives,” should benefit all taxpayers. Instead, workers stand to earn bonuses if they exceed the health plan’s savings targets.

Another $200 million over four years will be drawn from dollars the city set aside in a stabilization fund, a reserve it finances alone but jointly controls with labor to cover higher costs of some city insurance plans. In the past, the unions would not allow Bloomberg to cut costs by tapping into that money.

The New York state comptroller determined, after accounting for dollars saved by slower premium growth and “administrative actions,” that the plan would directly save $544 million, 16 percent of its $3.4 billion goal.

Some critics have also complained that the administration agreed to negotiate practices that should happen anyway as a matter of good government. For instance, the agreement will achieve $400 million in savings from auditing insurance rolls for ineligible recipients, such as divorced spouses or adult children; Bloomberg tried to do the same thing, but the unions were able to block him.

Yet the former mayor’s difficulty in achieving some of the compromises de Blasio has won suggests that the ability to make even small gains, in a city with a still-powerful labor sector, can’t be taken for granted.

“I’m a little sympathetic to them,” said Brecher’s colleague Maria Doulis, vice president of the Citizens Budget Commission. “They’re establishing a precedent here to say: ‘We’re settling collective bargaining contracts and we’re putting in health insurance into how we think about this.’ It’s my hope that having accomplished that once it becomes part of how collective bargaining is done in New York.”

The city will find out next year: Many of the de Blasio union contracts are expiring this year or in 2018, including agreements with the United Federation of Teachers, DC37, the communications workers, and 1199SEIU, which represents health care workers and is the country’s largest union. The health care agreement, which was negotiated with the Municipal Labor Committee, a coalition of union leaders that represents nearly all New York City workers, ends June 30, 2018.

Barring an act of God, de Blasio will preside over City Hall for a second term, and unlike in 2013, when he wasn’t the labor favorite, unions began endorsing him more than a year before the 2017 election.

‘A historic and sweeping reform’

Mayor Bloomberg was never popular among workers, but he was initially a willing bargaining partner. The relationship deteriorated as large raises disappeared following the 2008 recession. By the time de Blasio took office, every municipal labor contract had been expired for at least three years, forcing the new mayor to reach terms with 150 bargaining units representing 300,000 workers impatient and demanding billions in missed and new raises the city couldn’t afford.

“This may be the hardest assignment that anyone in the history of labor relations in this city has taken on,” the mayor said when appointing Linn as labor commissioner on New Year’s Eve 2013. Linn had been former mayor Ed Koch’s chief negotiator in the 1980s, built a successful consulting practice, created benefit packages with a hospital union, and negotiated for the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the rank-and-file police union.

He targeted teachers, nurses, and hospital workers, who hadn’t received raises in five years. Just four months into the term, de Blasio announced that Linn had cinched a deal with the powerful UFT, which included an 18 percent wage increase over nine years, retroactive to 2009.

“The Bloomberg administration was willing to let city worker health care costs rise, rather than negotiate meaningfully with the municipal unions,” Michael Mulgrew, president of the 200,000-member teachers union, said in a statement. “But the de Blasio administration has worked with us, and the result is real reductions in what would have been the increase in health care spending.”

The UFT agreement was funded by “a historic and sweeping reform of public employee health care,” City Hall said in the first public mention of a savings agreement, which hadn’t yet been agreed to by the other unions. How these savings would be realized wasn’t explained.

Linn had also been shopping the health savings plan with Harry Nespoli, the Municipal Labor Committee head, who took a shot at Bloomberg. “I heard more worthwhile proposals in the first 45 minutes than I heard the previous three years,” he said after a meeting with Linn.

Nespoli did not respond to numerous calls for comment.

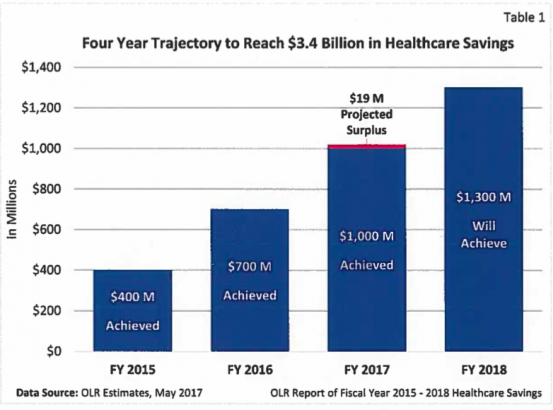

The commission approved the deal a few days after the UFT announcement, agreeing to meet savings targets of $400 million in fiscal year 2015, $700 million in 2016, $1 billion in 2017, and, in 2018, $1.3 billion. The $1.3 billion would recur annually, Linn explained in a later interview, because it lowered the starting point of ensuing years’ costs.

As a carrot and a stick, unions would receive any surplus up to $365 million above the $3.4 billion, but they were also responsible for delivering each year’s targeted savings even if they were unable to reach them through the agreement’s initiatives.

A labor official said savings were on track to exceed the target, but Linn said he was “not ready” to reach that conclusion.

In June 2014, a month after the agreement was reached, the citizens budget group criticized it as “a collection of one-time or temporary savings.“ A report cited surveys that forecast small growth in insurance premium costs. The city’s much-higher projections were responsibly arrived at “to protect taxpayers from damaging results,” the report said, but “do not reflect the contemporary dynamics of the health insurance market.”

“If insurance premiums decline due to economic trends,” it said, “and not because of any affirmative actions to improve the delivery of health care by the city and the MLC, those savings should be used to offset the expenses of city services, as they always have been, and not to fund raises.”

In April 2015, Linn explained to dubious city council members, who were just then seeing the actual reform measures, that it was on track to meet its $400 million first-year target.

“Many thought this was smoke and mirrors,” Linn said. “I think we’ve demonstrated they were absolutely wrong.”

As the watchdogs had feared, however, the city also realized first-year savings of $55 million because the premium costs of HIP HMO, the mostly widely used city plan, increased by 2.89 percent rather than projected 9 percent. Likewise, the premium costs for GHI Senior Care — a Medicare supplement — increased by 0.32 percent rather than 8 percent.

The pushback against counting these as savings created by the agreement was loud enough to move Linn and Dean Fuleihan, New York City’s budget director, to respond in a Daily News op-ed. They said city budget officers had made “prudent” projections based on growth rates over the past 15 years.

The reality of the system

In June 2017, Linn reported expected savings for the remainder of the agreement. Its incentives and price controls, over its last two years especially, appeared to be encouraging better use of medical care. To reduce use of emergency rooms for routine care, for instance, co-pays for visits were tripled from $50 to $150. Programs for managing diabetes and radiology fees were said to have saved millions, as was improved extended care for those with prolonged illnesses or needing rehabilitation.

When it expires in 2018, the agreement will have saved $136 million over four years on specialty drugs, nearly $400 million from discontinuing benefits to those who aren’t eligible, and $135 million by a switch from the HIP HMO plan to the HIP HMO Preferred Plan, according to Linn.

“It is true that we were fortunate that the HIP rate did not go up or the Senior Care rates did not go up as projected,” Linn acknowledged. But, he says, without an “overall structure” that included savings from lower premium increases, the city wouldn’t have been positioned for other savings.

He said he doesn’t think people understood the magnitude of the changes. “Say the MTA has a 2 percent employee contribution to health. [It does.] That would save the city maybe $300 million annually. That is well below the $1.3 billion annual savings that we’ll achieve by the end of the contract,” he said.

“The most important thing was that it helped change the whole relationship between labor and management looking at these problems.”

Some still see the agreement as at best a blown opportunity.

“To present it as a sacrifice on the part of the workers is what’s misleading,” said Bill Hammond, director of health policy at the Empire Center, a right-leaning think tank. “That’s how this was framed to begin with: ‘These are things we traded for at the bargaining table. We gave them raises, they gave us health savings.’

“They should be bargaining for health savings at the table, but they shouldn’t be things the city can do of its own authority. They should be things you need to bargain for.”

The Citizens Budget Commission’s Doulis gives the city credit for getting the union to play along.

“The unions sue over everything, so things that seem like low-hanging fruit, that should have been done 20 years ago, should be done consistently, they sue and they win,” she said. “It blows our minds, but that is just the reality of the system we have here.”

To this way of thinking, those who believe Linn has oversold the agreement may not have accounted sufficiently for the difficulty of collective bargaining in New York City, even if only to change from a plan to a preferred plan or to find out if anyone is getting insurance who shouldn’t be covered.

Health care costs continue to rise, at any rate: about 4 percent annually in the city over the past four years, which Linn compares to about 7 percent nationally. The city comptroller projects 7.4 percent annual growth over the next three years. Three in 10 Americans say they have trouble paying their medical bills, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

“When we said we would bend the health care curve, we didn’t say we would turn it negative,” Linn said. “We changed the trend dramatically.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)