From Classroom Drudgery to Joyful Enrichment: The Evolution of Summer School

The pandemic supercharged summer school’s transformation from remedial academics to learning plus fun — and now there’s no going back, experts say.

On a sweltering Wednesday morning in July, a group of second graders gathered around their desks to inspect and prod at soil and plant vegetable seeds.

Their teacher engaged them in a call and response: “You can poke it!” she says. “You can?”

“Poke it!” they responded in unison before she added, “and take a little bit of dirt out!”

Down the hall, in a kindergarten classroom, kids spent the morning working on math problems before moving into a purposeful play session focused on fossils.

“I’m working on three plus three equals six … using blocks!” exclaimed one student, Gabriella, who shared that her favorite parts of the day are “snack and recess and lunch.”

Later that afternoon, she and her classmates headed to one of a number of extracurricular activities ranging from martial arts to step dance and soccer.

These students at New Bridges Elementary, a school which sits along a stretch of the Eastern Parkway in the heart of Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood, were participating in Summer Rising, a partnership between New York City Public Schools and the Department of Youth and Community Development. The program, launched in 2021 in the depths of the pandemic, gives students access to free academic and enrichment programming over the course of six summer weeks — a time when schools have historically been shuttered to all students except those in need of the most concentrated, remedial academic support.

New York City is one of scores of districts across the nation who have worked to transform traditional summer school into a more inclusive, enrichment-filled yet still academically rigorous space.

Some of these districts began this shift over a decade ago, following the release of a 2011 research report, which put forth a case for rebuilding summer learning and highlighted the ways in which this time could be used to fight some of the academic backslide typically seen between June and September, especially for students from low-income backgrounds.

These efforts were supercharged during the pandemic, when schools were faced with a learning loss crisis and, simultaneously, a seismic funding influx from the $189.5 billion Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, also known as ESSER.

The pandemic, “really lit a fire in everybody to say, ‘We can’t do things the same,’” said Nancy Gannon, senior advisor of Teaching and Learning for U.S. Education at FHI 360, a nonprofit which built the District Summer Learning Network to help districts and states rethink what can be accomplished during these down months.

“I don’t think people really dug into the potential of summer until these last couple years,” she added. “And now that they see how potent it can be. I don’t know that there’ll be any going back.”

But some districts and states are scrambling to hold onto this new vision of summer with ESSER money sunsetting, the recent freeze — then release — of the federal dollars that keep many of these programs afloat and a greater uncertainty about the very future of the U.S. Department of Education and all its funding streams.

‘It can be a joyful place’

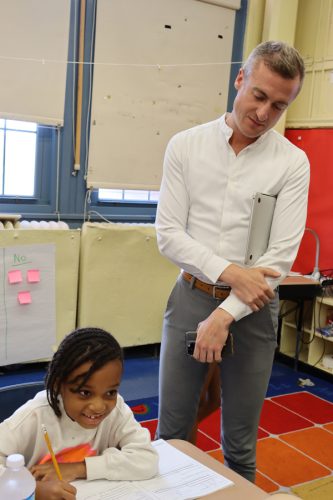

Kevyn Bowles, the principal of New Bridges Elementary, said he’s witnessed the transformation of summer first hand over the course of his 12 years running the school.

Historically, you were “bringing together the students who had done the most poorly over the course of the school year in eight different schools, and putting them all in a class together,” he said. “So even if you were bringing your most joyful teaching self to it, it still just was a challenging situation.”

Kids didn’t want to be there, he added, and it showed. That changed with the introduction of Summer Rising in 2021.

“Even from that first summer, it felt more like an opportunity for students,” Bowles said, “versus something that we were forcing just a small number of kids [to do] because they had quote, unquote, failed. … We had enormous demand”

This summer, around 250 elementary school students have signed up to attend Summer Rising at Bowles’ school, and fewer than 30 of them are mandated to be there.

Each morning, the kids gather in the auditorium at 8 a.m. for Bright Start, a five-minute morning meeting filled with songs, affirmations and high fives.

“To me that just sets the tone,” said Bowles, “like we’re here together. We’re in this together. It can be a joyful place. It can be a fun day.”

Kids next head to a half-hour block of social-emotional learning through yoga and mindfulness, followed by three-and-a-half hours of concentrated academics, taught by licensed teachers. After lunch and recess, students have their afternoon “specials” — including soccer, martial arts, theater and dance — which wrap up by 6 p.m. each evening.

Bowles said the vast range of enrichment activities they’re uniquely able to offer students over the summer bring a lot of happiness and motivation to the school building. And while attendance in July and August remains a challenge, New Bridges Elementary has seen positive results in math and reading, especially for the youngest students: Kindergarteners through second graders who attended Summer Rising in past years either maintained their skills or grew, whereas their peers who didn’t, slid slightly backwards.

“Summer learning arguably has the greatest impact at the lowest price on the greatest number of students of any policy solutions,” Chris Smith, executive director of Boston After School & Beyond, told The 74. “And it’s time that we invest in it in a serious way with public funding.”

‘A blank canvas’

For summer learning to be an effective tool to combat learning loss — rather than merely functioning as child care or summer camp — school leaders need to strategically implement research-backed best practices, experts and researchers told The 74.

From 2011-16 a group of RAND researchers studied voluntary, free and district-led summer learning programs for low-income elementary students in five urban school districts: Boston, Dallas, Pittsburgh, Duval County, Florida and Rochester, New York.

They found it was important to pair strong teachers with rigorous academic curriculum and high-quality enrichment experiences. Other recommendations include:

- Programs should run for five to six weeks with three to four hours a day of concentrated academics, including 90 or more minutes of math and 120 or more minutes of English Language Arts.

- Small class sizes, capped at 15 students per adult

- A clear attendance policy and incentives for showing up

- Recruitment and hiring of the district’s most highly effective teachers

- Curriculum anchored in school-year standards and student needs

- Early planning led by a program director who dedicates at least half of their time to this work, beginning in January

After two consecutive summers, students who attended one of these programs for 20 or more days outperformed their peers in math and ELA and displayed stronger social-emotional competencies, the Rand researchers found.

The pandemic provided a perfect opportunity for districts across the country to implement some of these practices, both because students had a heightened need of academic and social-emotional support and because of the unprecedented sum of federal rescue funds that were poured into schools. One-fifth was allocated to academic recovery, with 1% specifically earmarked for summer learning.

Because the money was distributed through states — rather than districts — this also invited them into the conversation, when historically summer programming had been locally driven by schools or other organizations. And this unique moment provided fertile ground for more research, according to Allison Crean Davis, the chief research officer at Education Northwest, who also directed a three-part National Summer Learning & Enrichment Study funded by the Wallace Foundation.

“Never had we seen this natural experiment where it’s like, ‘We’re going to give 1% of these large funds to states to then tee up summer learning … all across the country [and] give some of that money to districts to actually do it,’” she said. “So it just felt like it would be a real missed opportunity not to say, ‘What does this end up looking like? How do states respond?’”

She and her team found that 94% of the local education agencies they studied offered some kind of summer programming in 2021. Of those that did, all implemented academic programming, 59% were traditional “credit recovery” programs aimed at students who had failed and 57% supplemented academic programs with social-emotional learning.

RAND also expanded on its earlier research during the pandemic and found that 81% of schools nationwide offered summer programs in 2023, yet districts’ largest summer programs typically enrolled less than half of eligible students and less than 1 in 5 of the largest elementary programs met the minimum recommended hours of academic instruction.

Despite some of these ongoing trials and errors, summer remains an exciting space for innovation and collaboration, said Julie Fitz, a researcher at the Learning Policy Institute.

“Summer is just an interesting space where you have a little bit of a blank canvas, and states were getting really creative with thinking about how to design that space,” she said.

It also became an area of rare bipartisanship, she added. “It’s just been so refreshing to see people coming together around kids and putting the needs of kids and families first.”

‘Little shy about investing in summer right now’

This is the first summer since the pandemic that most states are navigating summer school without COVID relief funds — and with increased uncertainty about federal education spending more broadly.

While the hope initially was that districts and states would find ways to sustain programming after that fiscal cliff, many remain concerned that even basic “foundational funding” needed to educate students might disappear, Davis said.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if people are a little shy about investing in summer right now,” she said.

This tension became especially apparent on June 30, when the Trump administration announced it would withhold almost $7 billion in previously allocated money, including $1.3 billion for the 21st Century Community Learning Centers, which districts rely on to run afterschool and summer programming. The news came one day before schools were meant to receive the money.

“This type of uncertainty — where they thought they were going to have it, and then all of the sudden we’re told the day before they expected to be given it, to no longer have it — is unprecedented,” said Tara Thomas, government affairs manager at The School Superintendents Association.

The move disproportionately harmed smaller districts and those serving larger populations of students from low-income families, “because they didn’t have money to float these services while they wait to figure out if the federal government is going to give them the money that they were promised,” Thomas said.

Following widespread, bipartisan pushback, the Office of Management and Budget said on July 18 that they’d be releasing the $1.3 billion for afterschool and summer programs, although a lawsuit filed by two dozen states after the sudden freeze alleged critical academic and extracurricular programs had already been “irreparably harmed.”

Despite these hurdles, researchers and district leaders remain excited about where summer learning is headed.

“I think it’s really encouraging and there’s a lot of vision about how summer can be an important tool in the state toolbox in terms of improving educational outcomes and other social focus areas,” said the Learning Policy Institute’s Fitz. “I think it’s really an optimistic area right now.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter