Friedman: Some Colleges Do an Amazing Job of Boosting Income Mobility for Low-Income Students. Now, How Do We Get More of Them to Enroll?

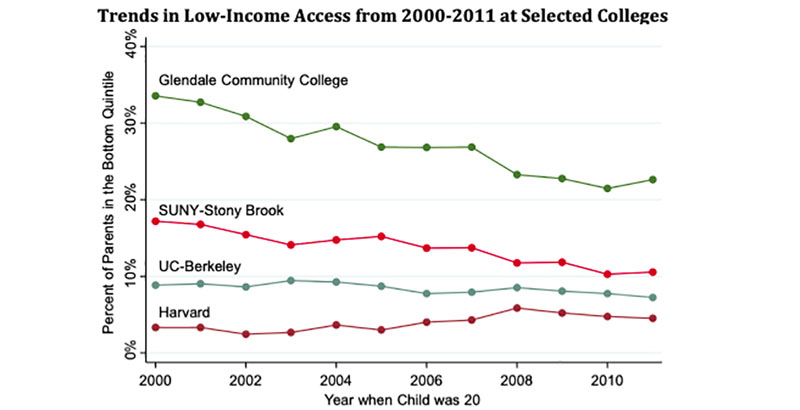

In 2017, my colleagues at Opportunity Insights and I released Mobility Report Cards: The Role of Colleges in Intergenerational Mobility, using anonymized federal data for each college in the U.S. on the distribution of graduates’ earnings in their 30s and their parents’ incomes. We found that low-income students achieved such excellent outcomes after attending selective schools — outcomes nearly as high as for their same-college peers from high-income families — that these schools level the playing field across the parent income distribution. However, we also found relatively few low-income students attending these selective schools, limiting their potential effect on upward mobility. Some selective schools had more students from the richest 1 percent of families than from the entire bottom half of the income distribution.

This naturally raised the questions: Why are there so few low-income students at these schools, and what can be done about it?

Last month, we started to answer these questions in a paper that examines whether the difference in the types of colleges that children from low- versus high-income families attend is explained by differences in their qualifications. We also analyzed the extent to which changes in the college application and attendance process could reduce income segregation across colleges and increase intergenerational income mobility. We did so using data on students’ ACT and SAT scores as a proxy for their pre-college qualifications. Although test scores do not capture all aspects of students’ qualifications, they are strong predictors of future earnings, even for students from the same socioeconomic background attending the same college, and therefore serve as a simple summary measure of pre-college credentials.

We found that low- and middle-income students attend selective schools at lower rates than their peers from richer families, even when they have the same qualifications. Despite having the same test scores, high-income students are 34 percent more likely to attend selective colleges than low-income students.

The picture is slightly different among the most selective schools — the Ivy League, plus Chicago, Duke, MIT and Stanford — where middle-class students are most heavily underrepresented relative to other students with the same test scores. In contrast with recent research, we found that low-income students attend these Ivy-plus schools at lower rates than high-income students but at significantly higher rates than middle-class students. Overall, low-income students are only slightly underrepresented relative to all others with the same test score; for instance, the percentage of students from the bottom 20 percent of family income would increase only from 3.8 to 4.4 if one eliminated differences in attendance between students with the same test score. There is thus a “missing middle” in the distribution of Ivy-plus students, which reflects how middle-class students are especially underrepresented at these schools.

Broadly, our results suggest that one could achieve major changes in economic diversity at selective schools, even taking as given students’ academic preparation at the end of high school, simply by equalizing attendance rates at each school among students with the same level of academic qualification. But because high-income students on average score higher on standardized tests, the student bodies at selective schools would have a smaller share of low-income students than at less selective schools.

What would it take to fully equalize the representation of low-income students so that the student body at each college reflected the composition of all college undergraduates in the U.S.? Intuitively, the attendance rate for low-income students would need to match that for high-income students with higher test scores. We calculate that this would require matching the attendance rates of high-income students with SAT scores 160 points higher. This is a large differential, but it is similar to the well-documented boost in admissions processes at many (especially private) schools for legacy students, minority students and recruited athletes. A direct admissions boost is not necessarily the best way to achieve these attendance gains — for instance, one could also increase application rates or yield rates among low-income students — but it does suggest that it would not necessarily require policies at a different scale than those already in practice for other groups.

Increasing the representation of low- and middle-income students at selective colleges would have a dramatic effect on intergenerational income mobility in the United States. Ensuring that students with the same qualifications had the same opportunities to attend college, regardless of their family income, would reduce the intergenerational mobility gap between high- and low-income students by 15 percent. If students attended colleges in a fully representative way, using the 160-point boost discussed above, this would reduce the gap by 25 percent. Although this would not close the entire gap, it would represent significant progress, given that children’s outcomes in adulthood are shaped by an accumulation of environmental factors starting from birth.

Overall, our findings suggest that changing the colleges that students attend could increase intergenerational mobility, even without changing college curricula or addressing disparities before students apply to college. We now aim to understand how to change which colleges students from low- and middle-income families attend and to identify scalable solutions.

To turn this research into action, we formed the Collegiate Leaders in Increasing MoBility (CLIMB) Initiative, partnering with a diverse array of colleges and universities across the country that currently enroll 30 percent of the entire U.S. undergraduate population. These partnerships are critical, since the best policies for enrolling more low-income students or promoting their success at one school may be very different than at another; what works in New York City may not work best in rural Texas. All of us benefit if society tries new ways to lift more children out of poverty.

John Friedman is co-director of Opportunity Insights at Harvard University.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)