Four Years After COVID, Former Superintendent Susan Enfield Looks Back with Pride — and Regret

The former Washoe County superintendent reflected on the lockdown, putting health and family first and having ‘playbooks’ for the next pandemic.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Four years ago this week, more than half of the nation’s schools closed their doors as the threat of COVID-19 grew more serious by the day.

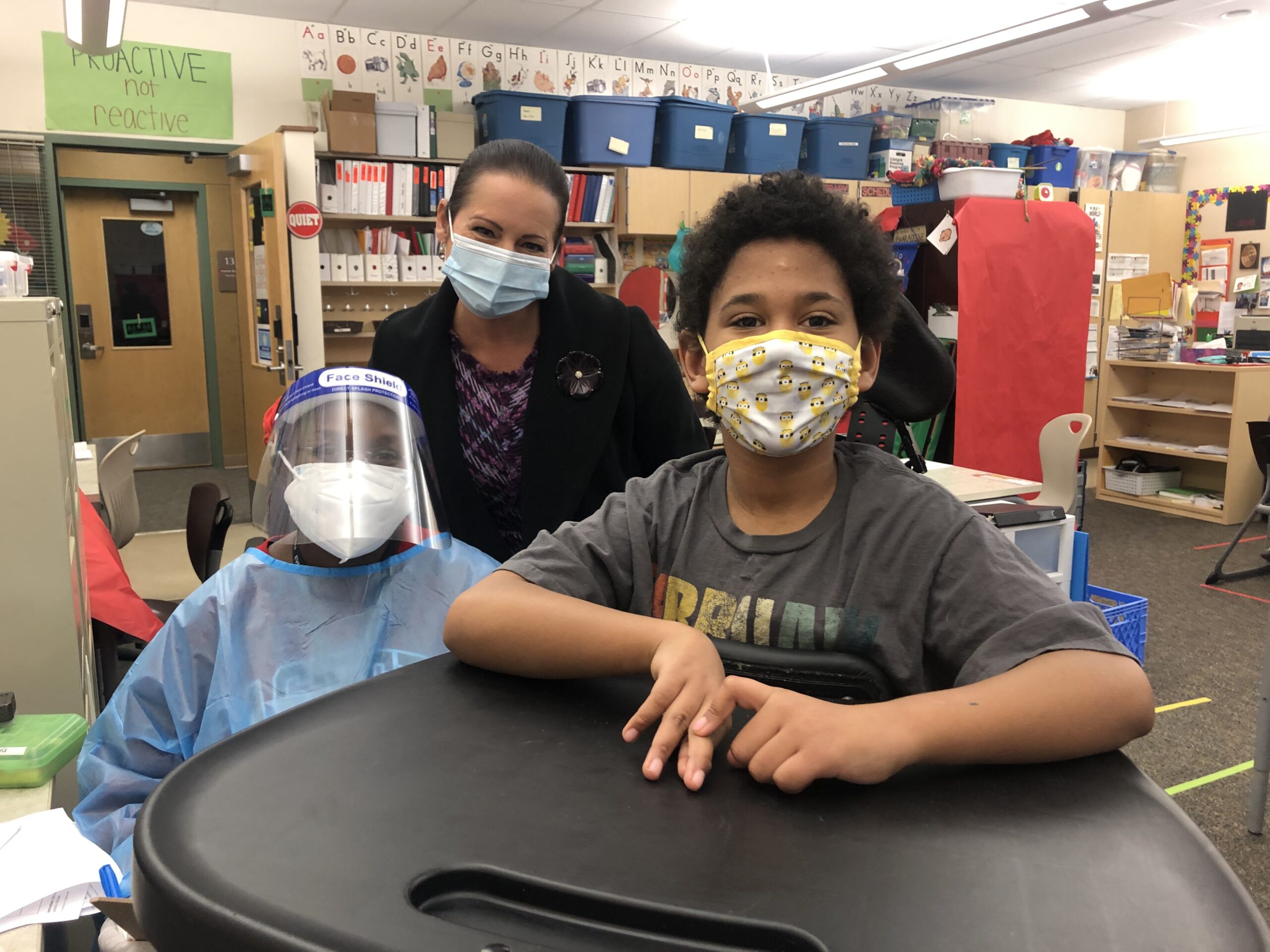

At the time, Susan Enfield was superintendent of the Highline Public Schools outside Seattle, close to the site of the first U.S. outbreak. Like her counterparts in neighboring districts, she was still in disbelief that sending students home was even an option.

“I’m not sure, at the end of the day, that that was the right decision,” said Enfield, who recently shared her reflections with The 74. “I don’t think we’ll know for a long time how that really impacted all of us.”

As the debate over reopening that fall intensified, Enfield was outspoken about the no-win situation leaders were in as they struggled to balance the needs of students with the demands and fears of parents and employees. To her, the predicament felt like having “an enormous square peg that I’m trying to squeeze into a microscopic round hole.”

Like many families and educators over the months and years that followed, Enfield relocated, leaving Highline in 2022 for the larger Washoe County Public Schools in Nevada, which includes Reno. She described the move then as hitting the “superintendent lottery,” but ultimately, stayed just a year and a half. She resigned in December to return to the Seattle area.

“I’m really happy to be home,” she said. “I’m taking this moment to breathe and figure out how I can contribute from a different vantage point.”

In an interview, she reflected on the past 48 months and how the pandemic has — and has not — transformed the nation’s education system.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The 74: The Northshore School District, not far from Highline, was the first in the nation to close because of COVID. What comes to mind now as you recall those frantic early days of the pandemic?

Susan Enfield: I’m really in awe of what educators across the country were able to do under really trying circumstances. I’m proud of how we responded. If memory serves, we deployed over 13,000 devices within the first couple weeks of having to close schools. There’s a real sense of pride in how people came together in a time of serious uncertainty and stress and did what they could to take care of our kids.

For those of us that stayed closed for so long, I don’t know if that was the right thing to do. Thousands of kids were out of school for so long, and we know that’s had an impact on them.

Moving from Highline to Washoe, what differences did you see in how the districts approached the closures?

How districts approached it was tied to local politics. The Puget Sound area is the bluest of the blue, whereas Washoe is really purple, politically. Washoe kids came back a year before Highline kids. That was probably the right thing to do.

What Highline was able to do that Washoe wasn’t was device distribution. We had under 20,000 kids, but Washoe had over 60,000, so there’s a magnitude issue. Washoe is a vast geographical area, so it was a challenge for them to distribute devices. Those differences speak to how every district responded as best they could based on their local political context and just the sheer makeup of their district.

Was there anything you would have done differently?

We would all go back and probably do some things differently, but I also had to recognize what was within my control. Our governor mandated schools be closed. I didn’t know at the time that keeping schools closed would be so detrimental. But there was so much fear and uncertainty around the virus, especially for a district like Highline. We have a lot of multifamily, multigenerational homes. The fears people had were very real, very legitimate.

How did the last four years change you personally as a leader?

It fortified my values as a leader. I’ve always been a big proponent of health and family first, but that was really amplified — not just preaching it, but modeling it. I had to make sure that I was taking care of my people.

We have a saying out here when it’s a beautiful clear day: “Mountain’s out.” I remember one Saturday. I just tweeted out a beautiful photo of Mount Rainier and said, “The mountain’s out and it’ll be out again tomorrow.” For those of us in leadership roles, we really had to dig into who we were as people, what our values were. The pandemic had an impact, not just on our children, but our teachers and staff as well. They had to re-learn how to be in community with other people after being in isolation for so long.

What are the biggest lessons we’ve learned from the past four years?

During the pandemic, there was so much talk of “We’re not going back to normal” and I was like, “Well, I don’t want to be the voice of doom and gloom, but the muscle memory of a bureaucracy as large as the public education system in the United States is very strong.” I predicted that we would by and large go back to what we knew.

We learned some things and continue to do some things differently, like the option for virtual meetings. Family participation in [special education] meetings is up because now parents don’t have to take time off work. On the flip side, we still have a digital divide. We still have too many kids that don’t have access to the internet. There’s been some backsliding there.

One of the key lessons is that we can’t focus on instruction without focusing on the overall well-being of our children. We have to make sure that our kids, and staff frankly, get the resources they need to be physically, emotionally and psychologically healthy. For all of the opportunities that technology brought, being in person matters — seeing that face, being hugged, having someone look you in the eye and sit down with you.

There are various predictions about the chances of another pandemic in our lifetime. If that bears out, how do you think the system would respond?

We’ve got some playbooks now. We are better prepared because we actually have some blueprints on the logistical part of it. I don’t think it will be the scramble that it was before. And since many of us blessedly lived through the last one, I’m hoping maybe there won’t be the same level of fear and uncertainty that existed before.

I remember doing virtual happy hours with my family in California and a lot of them were literally wiping down their groceries and they weren’t going anywhere. Those of us in school districts couldn’t do that. I don’t think I ever felt that same level of panic and fear because I just couldn’t afford to. I had to help hand out meals.

Do you think schools would close again?

That’s a really good question. As much as I think closing schools for the length of time we did wasn’t the right thing to do, I know that officials in Washington state have pointed to the very low death rate that we had. I don’t know what the perfect answer is.

I was pretty critical of a lot of our elected leaders during that time, but in hindsight, I have more empathy and compassion. I do believe everyone was doing the best they could with what they knew.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)