Forgive Flint’s School Debt Now: One Lawmaker’s Bid to Help the Kids Poisoned By Toxic Water

Awash in poisoned water and failed leadership, Flint, Michigan now sits at the brink of a potential education disaster.

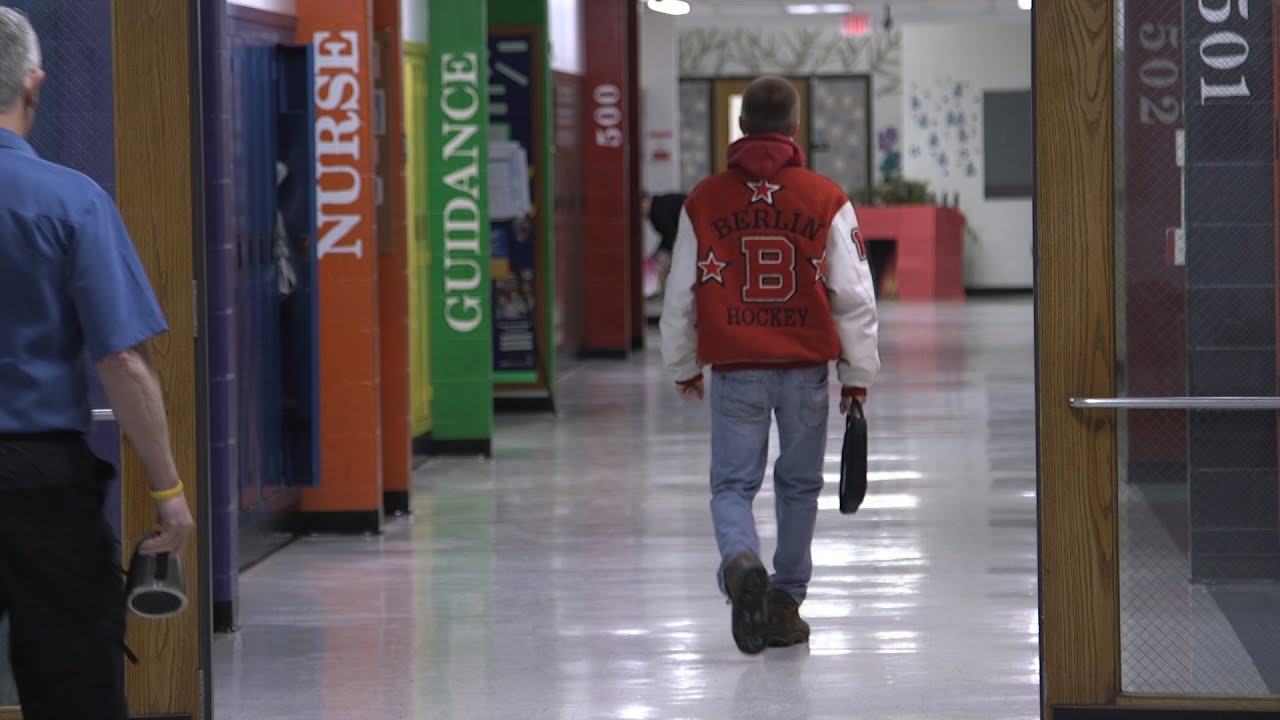

At least that’s how Sheldon Neeley sees it. The state representative, a Democrat from Flint and former city councilman, is publicly calling for an influx of financial support for the city’s crippled schools — demanding the state rush to assist the educators (and Flint’s sole school nurse) who now may well bear the brunt of the fallout of the toxic water crisis.

The estimated price tag of Neeley’s proposal: $10.5 million. That, says Flint’s superintendent, is the current debt facing the school district — a debt that Neeley is asking Gov. Rick Snyder to forgive. The move would ostensibly free up funds for the future care of an estimated 8,000 children younger than 6 who have almost surely been exposed to lead that seeped into Flint’s water system.

“The health of everyone, from newborn child to our senior citizens, was put at risk, but it is our children who will suffer the long-term effects of this catastrophe due to cognitive impairments associated with lead poisoning in young people,” Neeley said in a statement Jan. 8. “It is imperative that Flint Community Schools, which already struggle with financing for day-to-day operations, be given a clean slate to add programs to their schools to give the children of Flint every opportunity to succeed in spite of this crisis.”

“We cannot not allow them to be successful,” Neeley, who spent 10 years counseling at-risk kids in the district’s Career and Technical Education program, added in a interview.

The city’s water supply was switched from Lake Huron to the contaminated Flint River in April 2014, while Flint was under the control of a state-appointed emergency manager. The contaminated river water didn’t contain crucial anti-corrosion chemicals, and toxins leached lead from the water pipes through residents’ taps.

‘Living here, breathing here, existing here is really overwhelming right now’

The district of 5,400 students has only one school nurse, a situation Superintendent Bilal Tawwab said he inherited when he arrived in August from the struggling Detroit Public Schools, where he was an assistant superintendent. (Read our recent coverage: Crunching the numbers behind Detroit’s terrible schools)

Some $2.7 million of a total $28 million budget bill signed by the governor on Jan. 29 is expected to help the district hire additional nurses and provide early childhood and special education services. According to the bill, the $2.7 million will also be used for monitoring children from ages 0 to 3 for symptoms of potential lead exposure; coordinating (school) wraparound services; providing nutritional snacks to elementary school students; and providing and coordinating communications for parents, educators, and the community. (Federal lawmakers have also introduced legislation to expand Head Start preschool enrollment for Flint children affected by the water contamination.)

Tawwab said Neeley’s proposal to forgive the district’s debt and the state aid allotment are a good start in terms of aiding Flint’s struggling schools — but not nearly enough.

“You can say forgive the debt — that’s part of the conversation, that’s fine, but it’s going to take more than that,” he said in an interview. “There’s still going to be a high need for additional support. We need nurses, we need health centers.”

Tawwab said he’s now talking with Neeley and other local lawmakers, health officials and community activists about how to expand health services in the district, and add services for new mothers and their babies. He envisions each of Flint’s 12 schools having its own nurse and health center.

How the mechanics of a school district debt forgiveness plan would work remain unclear. A spokesman for the Michigan Department of Treasury, which is managing Flint schools’ finances under a new arrangement with the state Department of Education, said there are no existing state statutes that allow the debt to be forgiven. It could, however, possibly be addressed through new legislation.

Some observers questioned the political practicality of the proposal. “It’s positive, it’s hopeful, but do we think that will happen in a Republican Senate and House? Currently I think that’s going to be a hard sell,” said Dawn Demps, a Flint native and executive director of the nonprofit Urban Center for Post-Secondary Access and Success (UPASS).

Coping with the new normal

While lawmakers bicker over relief funds, Flint parents, students and teachers are still coping with the new daily realities of this man-made disaster.

Kelly Fields, an English teacher at Northwestern High School, said life in her hometown has taken a turn toward surreal in the last couple weeks.

Just the other day, she said, she spotted the rapper Snoop Dogg, in a red fur coat, standing on a street corner handing out bottled water. Other celebrities and do-gooders have come through the city distributing water, and Flint’s own, including Northwestern High athletes, have worked tirelessly to help their neighbors.

Fields recalled a poem one student wrote for her class recently about life in Flint that included the line: “If the lead don’t kill you, a bullet will.”

The gut punch of the teenager’s words sticks with her, Fields said, as she drives between school and home, teaching her students and taking care of her own kids, showering cautiously, drinking bottled water and testing her tap water for lead, over and over again. The district held a “Family Fun Night” recently with pizza, activities — and finger-prick lead tests for kids.

“I don’t want to sensationalize people’s experiences,” she said. “But living here, breathing here, existing here is really overwhelming right now.”

Tears stream down the face of Morgan Walker, age 5 of Flint, as she gets her finger pricked for a lead screening on January 26, 2016 at Eisenhower Elementary School in Flint, Michigan. Free lead screenings are performed for Flint children 6 years old and younger, one of several events sponsored by Molina Healthcare following the city's water contamination and federal state of emergency. (Photo by Brett Carlsen/Getty Images)

Flint students faced adversity even before the water crisis put the city of 99,000 — one of the poorest and most violent of its size in the U.S. — in the glare of a national media spotlight.

Located about an hour northwest of Detroit, the city is home to General Motors’ sprawling assembly plant. About 57 percent of city residents are black, and more than 41 percent live in poverty; median household income is $24,679, less than half that of the state average, according to U.S. Census data.

Flint school officials have closed, repurposed or demolished dozens of school buildings in the last 12 years, amid the auto industry’s collapse. The growth of charter schools and an open enrollment policy in neighboring districts account for some of the declining enrollment in Flint’s district schools.

Both the public high schools and two elementary schools are ranked among the lowest- achieving schools in Michigan; once the designation is applied, it lasts for four years, even if schools improve during that period. Some 83 percent of students are economically disadvantaged; about 58 percent graduate.

Fields said what’s been left out of the media portrayals of a destitute and damaged city is an acknowledgement of the tenacity of its youth. Her students at Northwestern High School have persevered throughout the “atrocity” that is the water poisoning while also living with “normal” circumstances that might include stepping off a school bus and into a crime scene on their block on any given afternoon, she said.

“I live in the same neighborhood that my kids come from and I see them every single day and I’m just so proud of them because I know that I’m struggling to take care of myself,” she said. “The community is going to need a lot and I’m hoping that our government (will) respond with the compassion to know that the right thing to do is to make sure that all kids are taken care of.”

Amber Hasan, a spoken word artist and mother of six, including a 1-year-old, said her family stopped drinking their tap water almost two years ago. She switched to using bottled water as much as possible for bathing, cooking and cleaning in July 2015, when residents began reporting issues with E.coli and Legionnaires' disease.

Hasan, who sends her three school-age children to nearby schools outside of the Flint district, said she could spend $300 a month just for drinking water, not including any other needs. Those costs add up.

“There are just some days where we don’t have enough bottled water to wash the dishes,” she said. When that happens, “We use the tap water and pray.”

Jake McSigue, 6, of Linden, receives a packahe of bottled water through the window of his grandma's home January 21, 2016 in Flint, Michigan. McSigue was home sick from school and staying with his grandma, whose front door does not open. The Red Cross is supporting state and county efforts to bring water to every household in the city. (Photo by Sarah Rice/Getty Images)

News that state officials knew about the unsafe levels of contaminants in the water and didn’t act have set off a wave of resignations and lawsuits in recent weeks.

Documentary filmmaker and activist Michael Moore, a Flint native, has been among the loudest voices demanding the Republican governor be held accountable for the situation. He’s called for officials to evacuate any Flint residents who want to leave and the creation of a temporary water system in each home for those who chose to stay, Michigan Live reported. As of Monday, more than half-a-million people had signed Moore’s petition urging U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch to prosecute Snyder. Meanwhile, federal officials have opened an investigation.

In his State of the State address two weeks ago, Snyder apologized to Flint residents and said the problem was due to a failure at all levels of government, Michigan Live reported.

"I'm sorry most of all that I let you down. You deserve better. You deserve accountability. You deserve to know the buck stops here with me," Snyder said.

Neeley, the state lawmaker, said Snyder hasn’t responded to his request to forgive the school district’s debt.

Asked if the governor would consider the debt forgiveness proposal, Snyder’s spokesman, Dave Murray, said in a statement that the $28 million budget bill, which includes the $2.7 million specifically for the district, “should be considered a first step” and that more aid for Flint and its schools can be expected as part of the governor’s budget proposal that will be introduced in the coming weeks.

Tonight, while the politicians debate budget lines, Amber Hasan will continue rationing her family’s bottled water.

More from The Seventy Four

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)