Fixing a System that Set Up Youth to Fail: Rhode Island Overhauls High School

Rhode Island aligns its graduation standards, makes FAFSA a requirement, adds real-world courses and ends seat time as a credit criteria

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Updated, Feb. 15

Rhode Island is phasing in new standards for high school graduation after a multi-year evaluation revealed that nearly half of graduates were not meeting the minimum criteria for entry into the state’s public colleges and universities.

The class of 2028 — current seventh graders — will be required to take at least two years of a world language and complete math courses in geometry and Algebra II in order to earn their diploma. Seniors will also graduate having written professional resumes and completed the federal college financial aid form, known as FAFSA, a first nationwide, Rhode Island officials say. (Some other states have also made FAFSA a graduation requirement but offer students alternatives, such as filling out a state-level financial aid application instead or seeking an opt-out.) At the same time, Rhode Island will support high schools to add offerings in computer science, civics and financial literacy.

The new regulations also add flexibility for students who work jobs or are caregivers to receive credit for their real-world learning experiences. The changes will eliminate seat time in the classroom from being a criteria used to award academic credit, placing the emphasis instead on subject mastery and student proficiency.

The State Council on Elementary and Secondary Education approved the new standards in November and officials are now beginning implementation.

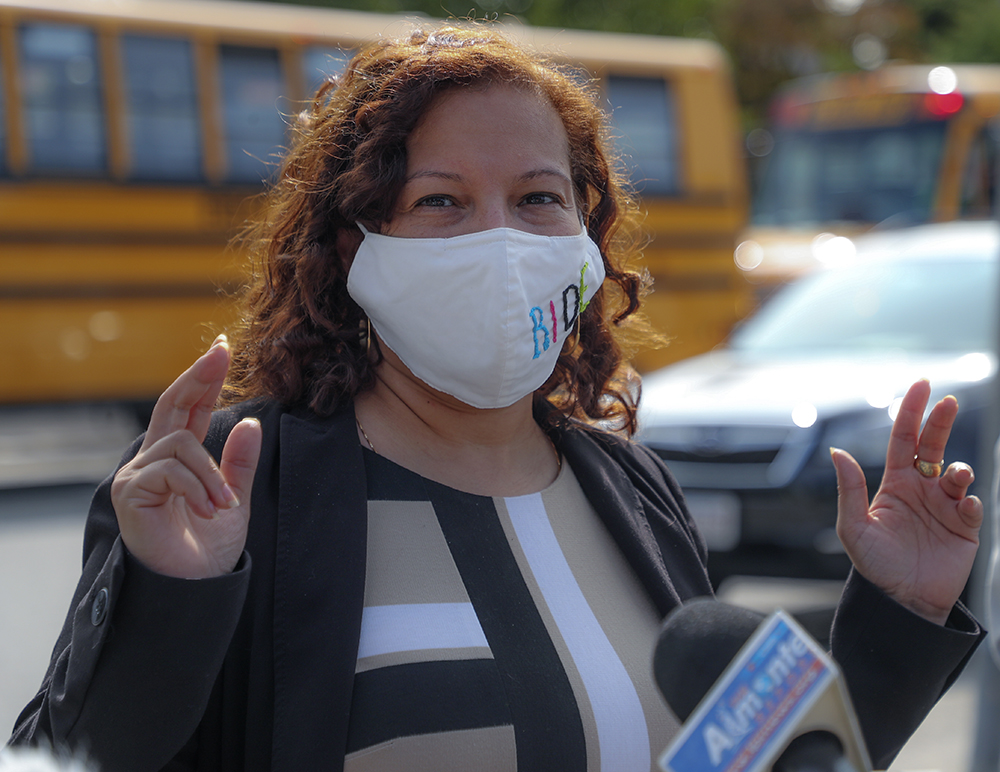

“This is going to be a gamechanger for us across the state,” Education Commissioner Angélica Infante-Green said.

The shift comes after the Rhode Island Department of Education partnered with the XQ Institute in 2020 to audit how well its high schools were preparing their students for success in college and careers. Researchers at the nonprofit analyzed more than 4,800 surveys and over 2,250 transcripts from a representative sample of students, finding that high schools were falling short on preparing their graduates for college and careers. They provided their work at no cost to the state.

While about 80% of students said they wanted to attend college, just 60% enrolled in the courses necessary to be eligible for higher education and only about 50% passed those classes.

“It was just really shocking to see the number of students that didn’t meet this bar of college eligibility,” said Keith Dysarz, who led the XQ analysis.

Low-income students, English learners and students with disabilities saw even wider gaps, with the first two groups completing college prep coursework 42% of the time while the latter hit that mark in just 12% of cases.

In many cases, high schoolers would sign up for classes and have no idea that their selections could disqualify them from access to higher education, Infante-Green explained.

“Kids didn’t even know that they were not being provided the courses [they needed for college],” she said.

She and her colleagues were surprised to find the issues were pervasive in school districts not typically thought of as struggling. Several urban school systems in Rhode Island have a reputation for needing improvement, with Providence and Central Falls both actively under state takeover for underperformance, but wealthier suburban districts were also falling short on college and career preparation, the commissioner said.

In Bristol, an oceanside town with roughly 3,000 students in a regional school district, Madison Rodriques said the college entry requirements were easy to miss. The only time she remembers hearing she needed two years of world language to be college-eligible was during a high school orientation at the end of eighth grade. Though she luckily was paying attention, she believes many of her peers were tuning out. Now a junior at Bristol’s Roger Williams University, she had to step in on behalf of her younger brother, who is a high school senior, she said.

“College wasn’t really on his radar when he was going into high school. I was the one to be like, ‘Oh, if you want to go, we need to do this and this,’” she said. “Not everyone has that older sibling or parent that’s going to be on top of that.”

After looking at the transcript data and holding 18 focus group conversations with students, state leaders acknowledged they had a problem to address. In the summer of 2021, they convened a working group that met over several months to hear the feedback of over 350 stakeholders.

“We do not want to be right; we’re here to get it right,” Stephen Osborn, the state education department leader spearheading the process, would tell educators and families.

Rodriques joined and spoke up about the disconnect between the courses laid out for her and her peers and the transcript requirements to be eligible for nearby colleges. She also advocated for more real-world skills like budgeting and how to do her taxes.

The leaders of the sessions “were so good at making sure voices were heard and elevated,” she said. “I could feel that they valued our presence there.”

The resulting proposal became the most commented-on set of K-12 regulations in the state’s history.

Now, schools are working to implement the new standards. Westerly High School Principal Michael Hobin is adding options for his students to gain certifications in life skills such as information technology, cosmetology or Spanish translation. He hopes that every member of the class of 2026, his current freshmen, will graduate with both a diploma and a credential awarded by an outside organization such as OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

“We want our kids … preparing for the rest of their life, whatever that means to them. If it means they’re going to go to college, then I want them prepared for college. If it means that they’re going into work, I want them prepared for work. If they’re going into the military, I want them prepared for the military,” Hobin said.

The new state regulations also call for more flexibility in awarding credit for the learning experiences students engage in outside the classroom. That’s a move to more equitably serve the numerous students in the state who are breadwinners for their family or caregivers, Osborn explained.

“Our kids are literally lifting their families out of poverty and then they’re being punished by their schools because they don’t have that time in their day to be able to go deeper into their academic schoolwork,” he said.

Schools may also combine courses for “flex credits” in two or more subjects, the new rules specify. That could mean delivering algebra in tandem with physics; English alongside performing arts or any number of other combinations, Osborn said.

Taken together, he hopes the standards send a clear message to school leaders.

“Coming from the Department of [Education], this is permission to be innovative.”

Disclosure: XQ provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)