First Robotics: A Building Competition That’s Now Gaining State-Level Support as In-Class Curriculum

Earlier this year on Jan. 8, more than 3,000 school-age teams of robotics students waited anxiously for the challenge that would consume the next six weeks of their creativity. With the challenge in hand, students — along with teachers and mentors — set about preparing for an eight-week competition schedule that culminates later this month as teams from 17 different countries come together in St. Louis to compete in the First Robotics world championships.

Even after 26 years, the nonprofit First (For Inspiration and Recognition of Science and Technology) hasn’t let up on growth, pushing to inspire more and more students around the world to pursue their passions in science and technology. “We want to help kids develop and discover a passion in science and tech they didn’t know they had,” Donald Bossi, First president, told The 74. “We want to get them to think like innovators.”

And robotics serves as the main model.

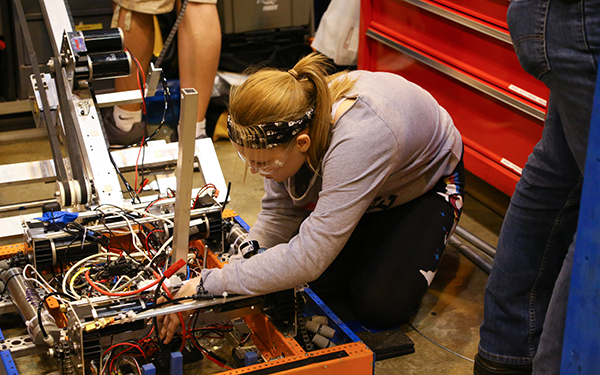

(Photo Courtesy: FIRST)

As part of this largely after-school program — schools can administer the program however they see fit and recent pushes now include the robotics challenge as part of classroom curriculum — teams of students must work together to turn a robotic kit into a high-performing machine that can accomplish a series of challenges while outdueling competitors along the way. With a basic kit to start and an end goal in mind, students can get imaginative and problem-solve along the way.

“In the information age we live in, it is not so much about what you know, but more about what you can do with what you know,” Bossi says. “Do kids know what to do with the math they learned?” Robotic competitions can serve as the vehicle to prove knowledge.

Late in 2015 Texas announced a plan to celebrate robotics in schools much as they already do with sports, giving winning teams the same banners and trophies handed out for state accomplishments in, say, soccer, football or basketball. State legislators in Michigan and Iowa, meanwhile, are now working to set up grants to help schools start more robotics teams. Already states such as Oregon and Washington have state-level support that offers financial assistance to teams, all while more and more schools take what was an after-school activity and push it into a hands-on classroom curriculum.

“Robotics teams in Texas will now have the opportunity to play at the same level as traditional sports teams,” says Ray Almgren, a vice president at National Instruments, a sponsor of the Texas program. “The state’s recognition of robotics means millions of students will now have access to robotics, and an opportunity to learn STEM skills in a hands-on way. This is a turning point for the widespread accessibility and adoption of student robotics programs across the state and nationwide.”

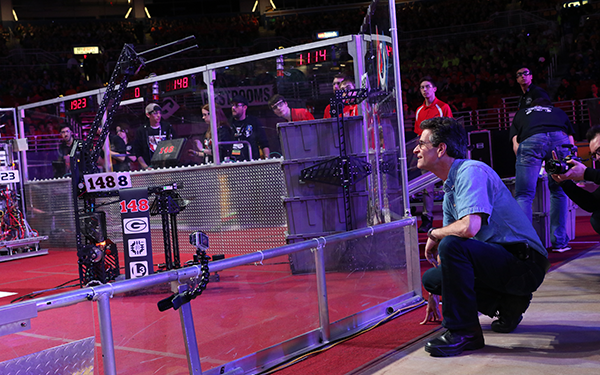

(Photo Courtesy : FIRST)

Bossi says that as First has grown — it was started by inventor Dean Kamen for high school students and has since added competitions for younger students and expanded beyond robotics, all while keeping a STEM-heavy focus in the 86 countries it reaches — the organization aims to create a cultural shift in students, showing them that science and technology have the ability to change the world.

“We make it like a sport,” Bossi says about taking cues from sports and entertainment, “make it fun, exciting and then motivated and inspired learning comes much more naturally, much more intrinsically.”

As students work side-by-side with mentors, teachers and classmates, they log meaningful education-filled hours, especially during the intensive six-week build that started in January. That six-week idea was constructed to give students a real-world constraint of not enough time, not enough resources. But even with the rigors of life, students have a finish date, with the eight-week competition schedule following closely on the heels of the build timeline.

“Really, that is where you learn teamwork, sometimes failure and sometimes how teams can overcome challenges and learn to work tighter,” Bossi says. “A heck of a lot of learning happens the night before a test. You can practice and practice and think you were good, but how did you do in the game, how did you compare? We think if competitions as an important component, but more of a celebration.”

(Photo Courtesy: FIRST)

Bossi says traditional academics don’t reward failure. But if failure signifies a “tremendous part of the learning process,” the competitions offer that, showing off a bevy of ideas, some better and some worse than others.

Looking beyond 2016, First is aiming to expand its demographics, reaching beyond its curent 35 percent female base and underrepresentation in schools with less privileged economic backgrounds. That is where a recent push for state funding comes to play. And that is where the varying degrees of benefit play out.

“There is no question that the kids who are naturally interested benefit from an outlet for their passion and being part of something fun and cool and helping them develop leadership and presentation skills,” Bossi says. “Then we also find that there are a whole bunch of kids who are not those kids; who if we can get them involved, it is really exciting.”

Who wouldn’t want to be a world champion roboticist?

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)