Fentanyl is Poisoning Arizona’s Teens. Students Are Reducing Overdoses, One PSA at a Time

A ‘No Second Chance’ campaign in nation’s fourth largest county demystifies the deadly synthetic opioid being found in vapes, counterfeit meds.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

This article is about youth drug use and death. Free, confidential treatment referral and information is available in English and Spanish at 800-662-4357, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s National Helpline.

Four teenagers take turns reading steadily from a teleprompter. Their message is as simple as their videos’ black and white color scheme: With fentanyl, there is no second chance.

“Look, I’m not here to preach. But you need to be aware of a serious issue,” begins one of now seven public safety announcements written and produced by Arizona’s Tempe Union High School District students.

In a conversational tone aimed at their Gen Z peers, the students calmly walk through party scenarios and life saving information about fentanyl, the synthetic opioid responsible for over 80% of all adolescent overdoses. As little as two grains of salt, approximately 2 mg, are lethal. The size of a pencil tip.

What began last fall as a marketing club project has since become a nationally-recognized, peer to peer fentanyl awareness campaign called “No Second Chance,” led by four students from two Tempe schools.

Students traversed Arizona and the country, leading local parent workshops and competing in an international competition to quickly spread the word about Good Samaritan laws, commonly laced recreational and counterfeit prescription drugs, and Naloxone or Narcan, the overdose reversal medication.

The federal Drug Enforcement Administration has just awarded the team a prestigious Red Ribbon for community drug awareness — one of two projects in the country to be recognized for their prevention work.

Students behind the campaign were motivated by the silence on the deadly trend that has claimed the lives of thousands of teens throughout their state.

“There’s this entire world underneath our feet,” Corona del Sol high school senior Jaia Neal told The 74. “And yet I don’t hear any of it on social media, or from any of my friends or parents or anything. It’s like, what is happening? How are people not freaking out that so many people are dying from this?”

A sobering CDC report released last year revealed that among 10 to 19 year olds, fentanyl-related overdose deaths increased 182% from 2019 to 2021. Two thirds of them were not alone when they overdosed.

Nearly all deaths were unintentional — less than 1% of synthetic opioid deaths from 2021 were ruled a suicide.

Such was the case for Ethan Dukes, 16. His mother, Shari, did not know why her early riser did not wake up one Saturday until the autopsy results came in.

In a way, No Second Chances’ campaign story begins with Ethan, the track athlete with dreams of being a parent and lawyer.

“One pill can kill — I always say one pill does kill. One pill flipped my entire world around,” his mother, lifetime district administrator and local prevention advocate Shari Dukes said.

He had gone to bed early, by 10:15, after coming home from a party Friday night. At the time, February of 2019, fentanyl was not on her nor the district’s radar.

Shari told her family’s experience, and frustration over schools’ silence for over two years after Ethan’s death, to the school board and an old colleague, Tempe Union’s social emotional wellness director, Ron Denne Jr.

“I thought, if I don’t know and I’m so involved, then there’s got to be all these other folks. Your kid can’t go to bed one day and not wake up the next,” Dukes said.

Denne pitched their community relations team and Corona del Sol’s marketing club advisor — and students took the torch.

No Second Chance has been meeting and presenting with family survivors, local prevention specialists and National Guard and DEA drug trafficking teams. Their videos have been screened during video announcements at high schools within the district. Later this basketball season, some will make an appearance on the Phoenix Suns’ jumbotron.

For those who’ve been doing prevention work for years, the campaign is exactly what’s been missing: how to reach young people effectively.

In the few months since students wrote and recorded PSAs, the landscape has already shifted. The amount of counterfeit pills containing lethal doses has risen from four in ten to seven in ten, the DEA reports.

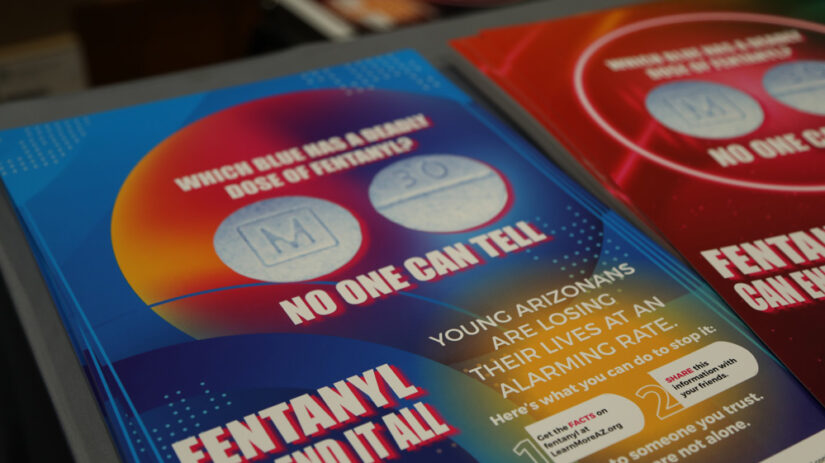

Teens are most commonly accessing fentanyl unknowingly from social media or secondhand from friends who have. Looking for prescription drugs, youth find laced, counterfeit Oxycodone, known as blue M30 pills, Percocet or Xanax.

“People don’t know what they don’t know… we want them to understand that there are bad people that are using social media platforms to sell drugs,” said National Guard Sergeant Tommy Morga, who helps lead the Arizona Counter Drug Task Force.

Compounding concerns, fentanyl is hard to accurately test for. Drugs are mixed unevenly; scraping one side of a pill may yield a false negative. Some THC vapes are impossible to take apart.

Just six years ago, fentanyl was a rarity outside of medicinal use as an anesthetic particularly for cancer patients. But the drug, 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, has ravaged parts of the country, particularly border areas, like Tempe Union’s Maricopa County, one of the nation’s most populous.

In Texas alone, eight bills have sought to authorize Narcan and emergency training for educators and schools. California passed their own version last month, requiring school safety plans include opioid training. In Nevada, advocates are pushing for harm reduction approaches like Tempe Union’s, instead of abstinence or zero tolerance messaging.

Almost immediately after the PSAs debuted at Tempe Union’s high schools, emails from teachers rolled in: thank you for showing these, my brother died of an overdose; my cousin is addicted.

Today, 10 doses of Narcan are available at five locations at each high school. Buses are stocked. About 50 students and 250 staff have been trained to administer it, including all nurses, security guards and transportation teams. QR codes to make confidential counselor appointments are posted throughout campuses. The districts’ teachers can access free counseling through Talkspace and longterm support via Care Solace.

At Corona del Sol, Neal never crossed paths with Ethan, four years her elder. But while presenting at a DEA teen academy meeting, she revealed her link to him, trading confidence for pained frustration.

How could they walk the same halls, have the same teachers, and not know Ethan died from fentanyl poisoning?

“How did we not know,” Neal asked, “how close it is to us?”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)