Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Offers New K-12 Achievement Gap Map, Intent on Changing Minnesotans’ Beliefs About Their Schools

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Most Minnesotans believe their schools are among the nation’s best. And for prosperous white students, they are very good. But for huge numbers of Black, Latino, Indigenous and Southeast Asian students, they are failing — a fact that is often met with disbelief.

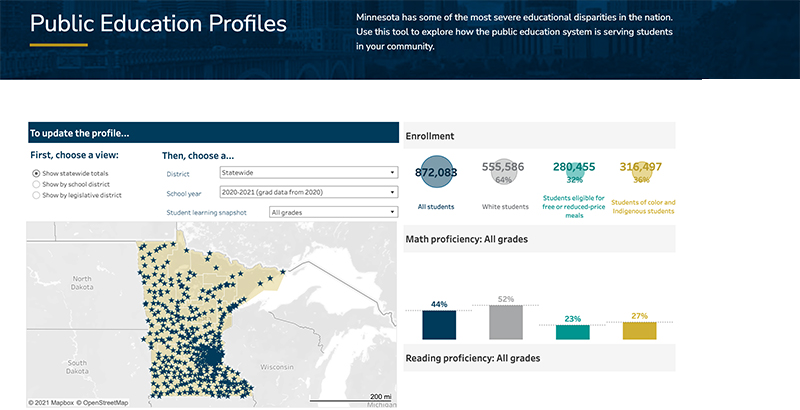

Now, to raise awareness of what it calls “some of the most severe disparities in the nation,” the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis has released a new data tool that allows people to see exactly how the public education system is serving children in their communities, including the state’s nation-leading racial and economic academic achievement gaps.

For the first time, voters and policy advocates can call up an educational profile for every legislative district in Minnesota, including all the school systems within its boundaries, student demographics, graduation rates and performance on annual reading and math tests. The information is broken out very simply, with charts showing performance among affluent and low-income students, and white and non-white and indigenous children.

The data tracker is notable for the new way it combines existing information. In the past, yawning disparities between the academic performance of children of different socioeconomic backgrounds were hard to tease out.

Test scores are available on the state Department of Education website, but broken down by subject, grade, disability status, income level and English learner status. Getting a picture of the overall gaps between white children and students of color required a lot of digging and tabulating.

Information about which schools are located in a given state electoral district is available, but a person would need to know to turn to the state’s little-known Legislative Coordinating Commission to find it. Likewise, it isn’t immediately clear that many of the state’s lowest-performing students won’t necessarily show up in district statistics after they have been transferred to alternative programs.

“The information landscape in Minnesota around educational outcomes is fragmented and complex,” says Vanessa Palmer, a data scientist with the Federal Reserve Bank. “It’s really hard for the average person, even the most passionate and committed community member, to see how all of the schools as a system and in their neighborhood are serving kids.”

The bank’s chief aim in creating the tool is to raise awareness that Minnesota’s achievement gaps are a statewide problem, rather than being an issue stemming from any particular type of school — charter, district, rural, suburban or urban. As such, they require a statewide solution, say Palmer and Alene Tchourumoff, the bank’s senior vice president of community development and of the Center for Indian Country Development.

Yet, advocates for more equitable education most often voice their concerns to local school boards instead of state lawmakers — who are responsible for the policies that directly influence how schools are funded, staffed and enrolled. Lawmakers decide things like teacher layoff and evaluation laws, how disparities in discipline are addressed and how much funding is directed to English learners and students with disabilities.

Tying the way schools are — or are not — serving students in legislators’ home communities rarely happens. “When you look at the responsibility from a policy standpoint … it really does fall with the legislature,” says Tchourumoff. “Minnesota’s constitution is written in that way. It’s directly within their core set of responsibilities.”

For example, the majority of Minnesota’s public education bucks stop, literally, with the chairs of the state Senate’s and House’s main education committees, respectively Republican Roger Chamberlain and Jim Davnie, a member of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party.

They rarely agree on how many bucks should be appropriated or how they should be spent, but each positions himself as a champion for children of color. It’s nearly impossible for voters to evaluate their policy prescriptions in light of the needs of the students in their particular community, or of the disparities in schools throughout the state.

Chamberlain’s Senate District 38 contains 83,000 suburban students who attend schools in a number of districts. Pre-pandemic, 71 percent of white District 38 students passed state reading exams, versus 53 percent of children of color and 47 percent of low-income kids.

His House counterpart, Davnie, represents a quadrant of Minneapolis where a traditional district and a number of public charter schools serve 41,000 children. Three-fourths of House District 63A’s white students read at grade level, compared with 29 percent of Black, Latino and Indigenous children, and 28 percent of impoverished ones.

Chamberlain is bullish on school choice, though traditional district schools in his relatively affluent legislative territory face little competition. Davnie is a staunch opponent, despite the fact that his community is home to some of the lowest-performing schools in the state.

As part of its mandate from Congress to maximize employment, the Minneapolis Fed has a history of conducting education research. Nearly two decades ago, it published a landmark study showing that for every tax dollar spent on high-quality early education, the return on investment was 16 percent. More recently, it has reported on the size of Minnesota’s achievement gaps and staged a series of events to explore racism’s economic impact.

In January 2020, bank President Neel Kashkari and former NFL star and Minnesota Supreme Court Justice Alan Page joined forces to propose amending the state constitution to recognize a “fundamental right to a quality public education.” State lawmakers would have to agree to put a proposed constitutional amendment on the ballot in order for it to take effect.

(Beth Hawkins)

Though Minnesota pioneered inter-district student enrollment and passed the first charter school law, the state’s education politics cleaves along traditional party lines, focusing more on funding than on improving schools. Lawmakers’ role in setting education policy is opaque at best to most voters, and the voices of families of low-income students and children of color who are disproportionately behind are rarely heard in debates at the Capitol.

Representing the Federal Reserve’s Ninth District, the Minneapolis bank also serves Montana, North and South Dakota, part of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)