Federal Judge Blocks Trump Bid to Kill Ed Dept., Orders Fired Workers Reinstated

A Massachusetts judge sided with education groups who allege March’s mass layoffs amounted to a shutdown of the agency without congressional approval.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

A federal judge on Thursday blocked President Donald Trump’s executive order to eliminate the Education Department and ordered officials to reinstate the jobs of thousands of federal employees who were laid off en masse earlier this year.

Judge Myong J. Joun of the District Court in Boston wrote in the preliminary injunction that the Trump administration had sought to “effectively dismantle” the Education Department without congressional approval and prevented the federal government from carrying out programs mandated by law.

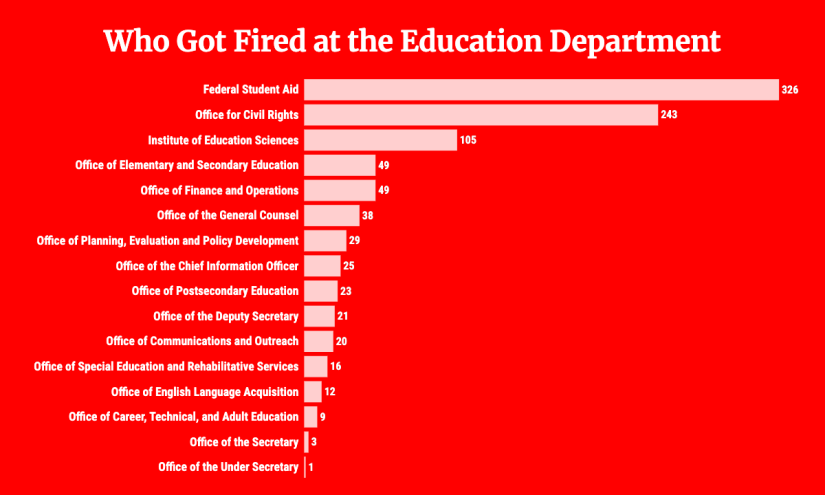

Trump administration officials have claimed the March layoffs of more than 1,300 federal education workers were designed to increase government efficiency and were separate from efforts to eliminate the agency outright, claims that Joun deemed “plainly not true.”

“Defendants fail to cite to a single case that holds that the Secretary’s authority is so broad that she can unilaterally dismantle a department by firing nearly the entire staff, or that her discretion permits her to make a ‘shell’ department,” Joun, a Biden appointee, wrote.

Combined with early retirements and buyouts offered by the administration, the layoffs left the Education Department with about half as many employees as it had when Trump took office in January. That same month, Trump signed an executive order calling on Education Secretary Linda McMahon to “take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education.”

The Trump administration has acknowledged it cannot eliminate the 45-year-old department — long a goal of conservatives — without congressional approval despite layoffs that have left numerous offices unstaffed. Yet there is “no evidence” the Trump administration is working with Congress to achieve its goal or that the layoffs have made the agency more efficient, Joun wrote. “Rather, the record is replete with evidence of the opposite.”

“A department without enough employees to perform statutorily mandated functions is not a department at all,” he said. “This court cannot be asked to cover its eyes while the Department’s employees are continuously fired and units are transferred out until the Department becomes a shell of itself.”

The White House didn’t respond to requests for comment. The Education Department said it plans to appeal.

In a statement, Education Department spokesperson Madi Biedermann blasted the court order and called Joun “a far-left Judge” who overstepped his authority and the plaintiffs who filed the lawsuit to halt the layoffs — including two Massachusetts school districts and the American Federation of Teachers — ”biased.” Also suing to stop the layoffs is 21 Democratic state attorneys general.

“President Trump and the Senate-confirmed Secretary of Education clearly have the authority to make decisions about agency reorganization efforts, not an unelected Judge with a political axe to grind,” Biedermann said. “This ruling is not in the best interest of American students or families. We will immediately challenge this on an emergency basis.”

Cutting the federal education workforce in half — from 4,133 to 2,183 — undermines its ability to distribute special education funding to schools, protect students’ civil rights and provide financial aid for college students, plaintiffs allege. They include the elimination of all Office of General Counsel attorneys, who specialize in K-12 grants related to special education, and most lawyers focused on student privacy issues. Plaintiffs also allege the cuts hampered the agency’s ability to manage a federal student loan program that provides financial assistance to nearly 13 million students across about 6,100 colleges and universities.

The Office for Civil Rights was among those hardest hit by layoffs, with seven of its 12 regional offices shut down entirely. The move has left thousands of pending civil rights cases — including those that allege racial discrimination and sexual misconduct — in limbo.

Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, called the temporary injunction the “first step to reverse this war on knowledge.” Yet the damage is already being felt in schools, said Jessica Tang, president of the American Federation of Teachers Massachusetts.

“The White House is not above the law, and we will never stop fighting on behalf of our students and our public schools and the protections, services and resources they need to thrive,” Tang said in a media release.

In interviews with The 74 Thursday, laid-off Education Department staffers reacted with cautious optimism. It remained unclear if, or when, they might return to their old jobs — or if they even want to go back.

Keith McNamara, a laid-off Education Department data governance specialist, said he’s “tempering my enthusiasm a bit” to see if Joun’s order is overturned on appeal. But he said he was “ a lot more hopeful than I was yesterday” about the potential for the department to return to the way it operated prior to the cuts.

For federal workers, he said the challenges have been ongoing and monumental, saying the last few months without work have “been very chaotic.”

“It’s been very difficult to look for other work because tens of thousands of us are all pouring into the job market at the same time,” he told The 74. “It’s been very stressful.”

Rachel Gittleman, who worked as a policy analyst in the financial aid office before getting terminated, called the court order on Thursday “a really broad rebuke on the administration’s attempt to shut down this critically important department.”

“But in many ways, the damage has already been done” as fired employees begin to find new jobs, Gittleman said, and Education Department leadership works to push people out.

McNamara said it was unclear Thursday whether the department would order fired employees back to work. Nearly his entire team was eliminated, he said, so it was uncertain what work he might do if he returned to the job. Asked if he was interested in doing so, he responded “I’d have to really think about that.”

“Quite frankly, I don’t think this administration is taking the job that the Education Department is supposed to be doing very seriously,” he said. “I’m not sure I’d want to work for an agency that — from the very top — is hostile to the work that the department does.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)