The Fact-Check is The Seventy Four’s ongoing series that examines the ways in which journalists, politicians and leaders misuse or misrepresent education data and research. See our complete Fact-Check archive.

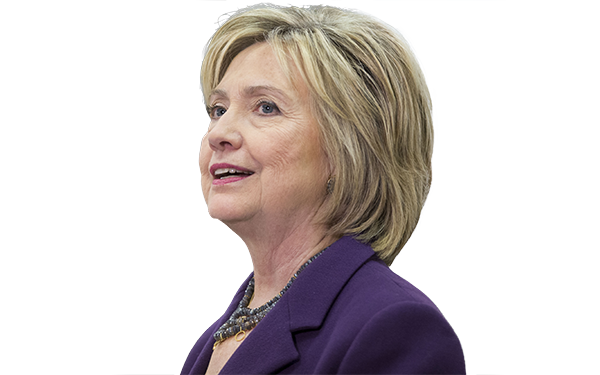

Last weekend Hillary Clinton took a shot at charter schools heard round the education world. In an interview with journalist Roland Martin, she said:

“Most charter schools — I don’t want to say everyone — but most charter schools, they don’t take the hardest-to-teach kids, or, if they do, they don’t keep them. And so the public schools are often in a no-win situation, because they do, thankfully, take everybody, and then they don’t get the resources or the help and support that they need to be able to take care of every child’s education.” (Read our exclusive interview with Roland Martin about Clinton’s charter comments)

Clinton’s claim, about charters not taking “the hardest-to-teach kids” is a common one. But does the data bear it out?

In a word, kinda. It depends on how “hardest-to-teach kids” is defined and whether charters are compared to all traditional public schools or just those that are in the same neighborhood as charters.

Clinton clearly overgeneralized, ignoring the key fact that charters serve large numbers of low-income and low-achieving students; there’s also little evidence that charters harm traditional public schools. Still, she’s raised a genuine issue that charter advocates should take seriously.

Here’s what the data say about her argument:

Broad generalizations about charter schools nationally are very difficult.

It’s important to start with this point. After all, charters operate under different laws in different states, and individual schools have diverse missions, catering to different students. Some charter schools teach, for instance, students at risk of dropping out, while others may be serving as a method of white flight from more integrated traditional public schools. Compounding this problem, is the limited research we have on different states. Most rigorous evidence comes from just a handful of higher-profile districts. That said, we’ll do the best with what we’ve got.

Compared to traditional public schools as a whole, charter schools serve more students of color, more low-income students, fewer special education students, and about the same number of English-language learners.

In a simple head-to-head comparison, national data finds charters as a whole are much more likely to serve students of color, particularly black students, than all traditional public schools. (This data is from the 2011–12 school year.)

Again based on national data, charters serve slightly more students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, a common, though imperfect, proxy for low-income status. This may understate the disadvantage of charter students, because about 18 percent of charters don’t participate in the federal lunch program, compared to just 3 percent of traditional public schools.

National data show charter schools serving a slightly lower number of students who are classified as special education and virtually the same number of English-language learners. Keep in mind that schools make decisions regarding the classification of students in each of these categories, so differences between sectors may reflect those subjective choices.

Compared to neighboring traditional public schools, charters serve less disadvantaged students by some measures but not others.

A more appropriate comparison may be between charter schools and district schools in the same area, since charters are not located evenly across the country. Here we see that charters serve about the same number of low-income students, a higher number of black students, and a lower number of special education students and English-language learners. There is also some evidence that in certain areas, district schools are more likely to serve very low-income students, the ones who qualify for free lunch, not just reduced priced.

This supports Clinton’s claim.

Another way of looking at this question is not through socio-economics but prior achievement levels. One of the most sophisticated analysis of this question examined whether students moving from traditional public schools to charters had higher academic achievement than students who stayed put. The study looked at several states and cities including Ohio, Texas, Chicago and Philadelphia. “Students transferring to charter schools had slightly higher test scores in two of seven locations, while, in the other five locations, the scores of the transferring students were identical to or lower than those of their (traditional public school) peers,” the report concludes.

Based on prior achievement, there is much less backing for the idea that charters take the easiest-to-educate kids.

There is limited empirical evidence that charter schools are systematically pushing out hard-to-serve kids — but only a handful of studies exist.

Arguably, Clinton implied that some charter schools push out difficult-to-educate students. The most, recent high-profile example of this comes from the New York Times’ story on Success Academy’s “got-to-go” list, and similar

concerns exist with many other charters.

(Disclosure: The Seventy Four’s editor-in-chief Campbell Brown serves on the board of Success Academy. She was not involved in the editing of this article.)

Empirical studies on this question are limited, but recent research has found no evidence that charter schools as a sector systematically push out disadvantaged students — at least not any more so than traditional public schools. That doesn’t mean that illegal push out never happens — obviously it does — just that research to date has not found consistent, sector-wide evidence of it.

Research from Marcus Winters, a professor at the University of Colorado–Colorado Springs and senior fellow at the pro-charter Manhattan Institute, on Denver and

New York City show that in both cities’ there was a gap in the number of special education students and

English-language learners between charters and district. The primary driver of this is that such students are less likely to apply to charters in the first place — not because those students are more likely to leave charters.

1

In fact, in some cases these students are less likely to leave charters than traditional public schools. Winters found that low-performing students were no more likely to leave charters than district schools. This evidence squares with a separate

study from an anonymous urban school district.

In sum, this research further supports the notion that neighboring district schools on average are serving more special education students and English-language learners, but not that charters as a whole are pushing out those students. However, the evidence here is limited to just a handful of cities and in some cases just a handful of grades within those cities.

Charter schools’ backfilling policies may exacerbate this issue.

There is significant controversy about whether charter schools should be required to “backfill” — that is replace the students who leave with new ones. Traditional public schools generally take all students in an enrollment zone even if they arrive in the middle of the school year. Some charter schools follow this policy, but many others don’t.

Since disadvantaged students often change schools frequently, charters that don’t backfill may have an easier-to-educate population of students, particularly over multiple years. In contrast, district schools may have a revolving door of mobile, at-risk students. A study of 19 KIPP charter middle schools from several different states showed the network’s student population becoming more advantaged over the course of multiple grades, in part because, unlike neighboring district schools, KIPP replaced fewer students who left. Notably though, the researchers found that this was unlikely to explain the large achievement gains of KIPP students.

Charter schools generally have no effect or a small positive effect on the test scores of nearby traditional public schools.

There is evidence that traditional public schools serve a more disadvantaged student population than neighboring charters, at least as measured by special education status. Because of this, it’s reasonable to expect that the district schools would suffer as charter schools enter their neighborhoods.

In fact, however, a large body of research suggests that charters generally have no effect or even a small positive effect on the achievement gains of nearby district schools.

It’s not clear why, but it rebuts the notion that charters are harming traditional public schools by leaving them with the hardest-to-serve students. Clinton described district schools as in a “no-win situation,” but in some cases the situation may be more like win–win.

Beyond the charter vs. traditional public schools wars

In her original comments, Clinton was speaking off the cuff and her brief remarks certainly contained a degree of truth.

When asked for comment, the Clinton campaign reiterated a previous statement from spokesperson Jesse Ferguson: “As Hillary Clinton has said, she wants to be sure that public charter schools, like traditional public schools, serve all students and do not discriminate against students with disabilities or behavioral challenges. She wants to be sure that public charter schools are open to all students.”

Yet the evidence is much more nuanced than Clinton let on. By some comparisons charters serve a more disadvantaged student population than district schools, though by others, they don’t.

Some districts have created common enrollment systems, designed to ensure a level playing field between charters and district schools. Others have encouraged

weighted lotteries to ensure that the most disadvantaged — low-income students, students with disabilities, English-language learners, and students who are migrant, homeless, or delinquent — have a better chance of getting into charter schools. It remains to be seen how effective such systems are.

Charter schools leaders also say they lack the necessary resources and economies of scale to provide services to severely disabled students

Discussing how to address these issues might be more fruitful than rhetoric, on both sides, that pits charters against traditional public schools.

Footnotes:

1. Some of the special education gap also results from the fact that charter schools are less likely to classify students as requiring special education services, and more likely to declassify those already labeled as such. (Return to story)

;)