Fact-Checking All Those Charter Critics Who Snatched Defeat from Jaws of New Orleans’ Victory

The Fact-Check is The Seventy Four’s ongoing series that examines the ways in which journalists, politicians and leaders misuse or misinterpret education data and research. See our complete Fact-Check archive.

No matter who you talk to, the sweeping reconfiguration of the New Orleans schools is a model for something.

To proponents, it’s a successful model of reform that should be expanded to other struggling public school districts.

To critics, it’s a top-down model of exactly what not to do when facing the daunting challenge of a long-troubled school district decimated by a natural disaster.

In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans dramatically expanded the number of charter schools in the city, fired existing staff, and held schools accountable for student test scores, closing those that didn’t hit certain targets. Today, almost all schools in New Orleans are independently operated, publicly funded charter schools.

Kindergartners smile on their first day of school at Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Charter School for Science and Technology in the Lower 9th Ward August 20, 2007 in New Orleans, Louisiana. (Photo by Getty Images)

The best study of what those ambitious changes brought to New Orleans schools, students and their families 10 years after Katrina — much-anticipated research by Tulane University economist Doug Harris — was published this week in Education Next.

Harris found that the combination of reforms produced large gains on almost every measurable outcome: from test scores to graduation rates, so much so that he declared in an interview with The 74: “I have never seen an effect of this size before.”

But such bold statements won’t mollify the New Orleans skeptics. Here’s a rundown of the criticism leveled at New Orleans’ reforms and some facts debunking each one:

It’s apples and oranges

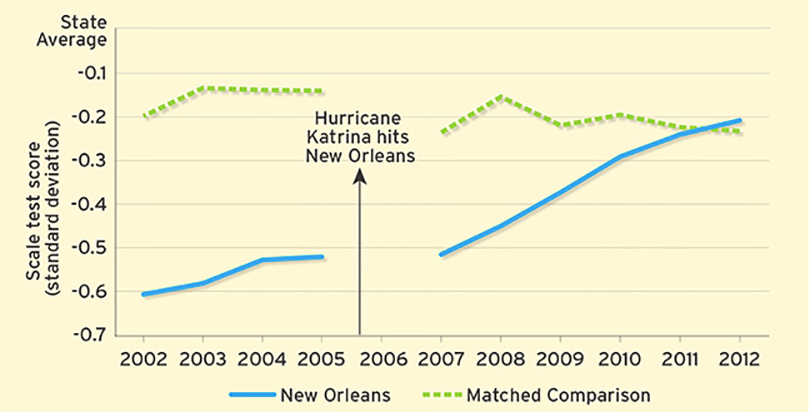

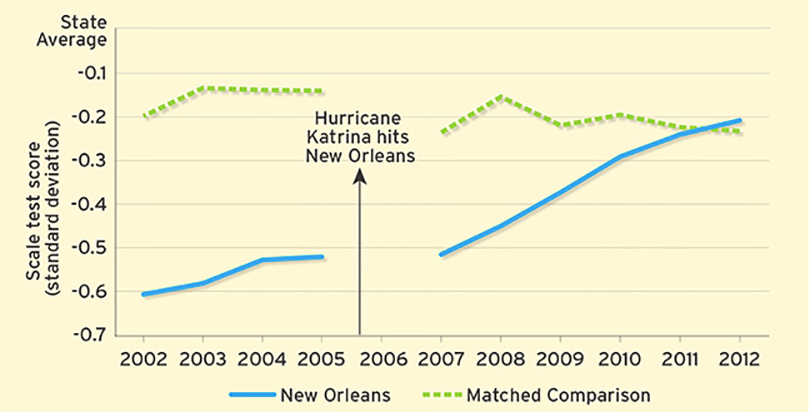

Examining the effects of New Orleans’ reforms is challenging since the pre- and post-Katrina student populations changed as a result of the hurricane. Harris addresses this in two ways: First by looking only at the growth of students who returned to New Orleans after Katrina and second by comparing all New Orleans students to students in other districts who were affected by Hurricane Katrina, which hit between Aug. 23 and Aug. 31, 2005, or Hurricane Rita less than a month later.

Neither method is perfect, but both are serious efforts to ensure apples-to-apples comparisons. The first method finds small improvements in student learning in test scores in math, English, science, and social studies. The second approach produces much larger estimates, finding that the city, which initially was massively behind the comparison group, caught up in just five years.

NOTES: Separate analyses show that New Orleans students returning after the storm, who could be studied only through 2009, also made gains relative to their own prior performance, but these differences were often not statistically significant. Scale scores are averaged across grades 3 through 8 and across English language arts, math, science and social studies. Scale scores are standardized so that zero refers to the statewide average. (Source: Education Next)

Combining both methods, Harris still finds significant positive results of at least eight percentage points for the average student. The upper end of Harris’ estimate is a massive 15 percentage point increase per student.

Who cares about test scores?

Research consistently finds that once high-stakes — such as the prospect of a school being closed or a teacher receiving a poor evaluation — are attached to tests, cheating, teaching to the test and other forms of gaming significantly increase.

As John Thompson writes in the Hechinger Report, “If [Harris] was studying a school system that was not totally focused on raising test scores during an era of data-driven competition, there would have been nothing wrong with Harris’s conclusion that New Orleans reforms increased student performance, as measured by test scores, eight to 13 percentile points, which compares favorably with expanding early education. Since No Child Left Behind, however, districts across the nation have reported miraculous increases on bubble-in tests, but test score growth on the reliable NAEP (National Assessment of Educational Progress) test has mostly slowed.”

Since New Orleans has used tests as a measuring stick of success for schools, it’s appropriate to be concerned that scores may be rising due to factors other than improved learning. If this were the case, one would expect that scores on high-stakes reading and math exams to have gone up much more than lower-stakes science and social studies tests. One would also predict that ACT scores would not have improved significantly since the college entrance exam is difficult to prepare for and externally administered, making cheating harder. Yet Harris found the same gains on both science and social studies tests, and that ACT scores improved by two points (on a 36-point test) in New Orleans since 2005.

Some may still argue that using any form of assessment to measure school quality is inappropriate because of long-standing skepticism of the value of standardized tests. But even ignoring test score growth as a metric of success doesn’t help reform skeptics: Harris finds big jumps in both rates of high school graduation and college entry of 10 and 14 percentage points, respectively.

Nothing to see here

Duke Professor Helen Ladd agreed that gains have been made but pointed out that the progress was “in the performance of students at a basic level — and it’s a very basic level.” A Politico story highlights that the average ACT score in New Orleans’ Recovery School District of 16.4 is “considerably below the minimum score [of 20] required for admission to a four-year public college in Louisiana.”

Similarly an article in ThinkProgress claims “New Orleans’ all-charter school system is struggling” pointing to data that finds “only a 2 point improvement” in aggregate ACT scores.

Yet an average two point increase on a 36-point exam is actually quite large statistically speaking. In an interview with The Seventy Four, Harris says the gains he observes on state tests are also massive: “Put differently, I’ve never seen an effect of this size before.”

The argument that the schools still have room to improve is one wholeheartedly agreed to by the supporters of the New Orleans reforms. But it does nothing to diminish the real growth in the schools based on multiple measures of success.

It’s all about the money

Ladd, the Duke professor, also argues that the main reason for the improvement was the large increases in per pupil expenditures, not the systemic reforms.

Ladd is right to say that money matters and that funding increases likely played a role in New Orleans’ improved school performance. After the storm, schools initially received large increases in resources. Harris estimates that “from 2004‒05 to 2011‒12, the same years covered by our achievement analysis, total public schooling expenditures per student increased by $1,000 in New Orleans relative to other districts in the state.” The average per pupil expenditure for Louisiana districts outside New Orleans is about $10,500.

Harris agrees that the resources were a contributing factor, but says, “There’s not much reason to think that it was all about the money.” He points out that many other urban school districts have seen serious infusions of funding without comparable gains.

They could have done it differently

Related to the more money argument is the more-money-and-different reforms argument. Teachers’ union President Randi Weingarten asks rhetorically, “Is there a way to actually have devoted the same kind of funding, the same kind of thought, the same kind of talent to do democratic, publicly accountable public schools?”

Harris rejects the suggestion that traditional investments would have produced the same results after looking at improvements made in schools that went that route. “We compared the effects that we generated to things like early childhood education and small class sizes and there just isn’t evidence generally to support the idea that that would generate effects of this size,” he says.

Less discipline, not more

Jennifer Berkshire (aka Edushyster), writing in Salon, points to the “strict disciplinary codes that are now the norm at many of the city’s charter schools.” A piece in the Atlantic says that in New Orleans “alarming numbers have begun to prompt challenges to and reassessments of charters’ no-excuses regimens.”

The harms of aggressive disciplinary practices are very real, and no doubt there are many schools in New Orleans that could improve on this front. Overall, though, Harris’ research finds that student expulsions and suspensions have decreased for all students since the reforms were instituted. Certainly there is continued improvement that should be made — and there is evidence that New Orleans charter schools are attempting and succeeding in addressing these problems to some extent — but the trend is moving in the right direction.

Segregating New Orleans

Writer and school reform critic Jeff Bryant argues in Salon that charter schools have an “unquestionable link to increased segregation of students based on race and income.” In fact, the research is mixed on this front, but Bryant is certainly right that in some specific areas charters may have exacerbated segregation. Did this happen in New Orleans?

Nope, finds Harris, who reports that segregation across a number of demographics has remained virtually unchanged since the reforms. That’s not to say that segregation is no longer an issue in New Orleans — it still is — but there’s no evidence that school choice made the problem worse.

Against popular opinion

The central thesis of Berkshire’s Salon piece, which features many New Orleans residents, parents, and activists is that the New Orleans community hasn’t bought into the city’s school reforms. Berkshire also suggests that a large number of people who were initially supportive of the turnaround reversed their position upon seeing its implementation.

She explains on Twitter that it’s been hard for her to find anyone who doesn’t criticize New Orleans’ reforms privately. That may be true, but the people who will speak on the record to a well-known charter schools critic may not be representative of the community as a whole.

A scientific survey of New Orleans residents finds that far more believe that the schools have improved since the storm than believe they’ve gotten worse; 59 percent agree that charter schools have improved education in the city; and 73 percent supported an open enrollment school choice system over a traditional geographic school assignment model.

The polling data is not all good news for proponents of the New Orleans model — white residents are more supportive than African-Americans, which is a major red flag — but there is no evidence that more people are skeptical of the system now compared to past surveys.

Another survey compared views of public school parents across several different cities — Baltimore, Cleveland, Denver, Detroit, Indianapolis, New Orleans, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. — and found that 56 percent of NOLA parents believe the schools there are improving. This was significantly better than most other cities, though slightly behind the reform-minded districts of Denver and Washington, D.C. Again, there is an important nuance here: just 42 percent of New Orleans parents expressed trust and confidence in the schools. But the overall picture is mixed to positive — not the one of widespread rebellion against the reforms Berkshire attempts to paint.

The schools haven’t cured cancer

Berkshire also says that New Orleans residents still face many obstacles: “The challenge for architects and advocates of the reform effort here is that, expanded even slightly beyond these narrow metrics [test scores, graduation rates and ACT scores], the case that life is improving for the children of New Orleans gets much harder to make. Child poverty stands at 39%, a figure that’s unchanged since Katrina, even though the city is now home to tens of thousands fewer children. Inequality is the second highest in the country, on par with Zambia. And violent crime remains a persistent plague here.”

To paraphrase education writer and activist, Chris Stewart, this can be called the “Well, it doesn’t cure cancer” argument against education reform. To expect successful school reform to cause immediate drops in child poverty or violent crime is laughable on its face — a bright red herring that if applied consistently would doom virtually every school reform effort ever tried.

—-

This is not an exhaustive list of the critiques of New Orleans school reform, but it addresses some of the main concerns that can be answered with the existing evidence.

None of this is to say that there aren’t valid questions about the success of New Orleans school reform experiment. For example, school choice advocate Howard Fuller has spoken eloquently about the process through which the New Orleans reforms were implemented on the community rather than with it.

Harris and others have noted the potential difficulties in trying to implement New Orleans reforms in totally different cities and contexts. The large-scale firing of African-American teachers left a significant wound in the community and its schools.

The case is not, as some claim, closed. Policymakers and community members need to continue to look at what’s working and what can be improved; researchers need to continue studying the district, using multiple measures of success, particularly long-run outcomes.

But let’s retire the arguments against New Orleans that, to date, aren’t based in fact.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)