Facing Mounting Financial Pressure, Los Angeles’s School District Is Asking for a $500M Parcel Tax. Its Biggest Barrier: Business Leaders Who Want Reforms First

As the nation’s second-largest school district in Los Angeles looks to sway residents to green-light its first-ever parcel tax, staunch opponents in the business and taxpayer communities say reform has to come first.

The heads of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce, Los Angeles County Business Federation, Valley Industry & Commerce Association and Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association said they take serious issue with L.A. Unified floating Measure EE, a $500 million annual tax on the June ballot that would burden taxpayers — businesses and corporations more heavily — without collaborating with their organizations, proving its accountability or mandating that revenue from the tax be spent solely in the classrooms.

L.A. Unified has continually failed to make internal reforms that curb its deficit spending and improve student outcomes, the executives say — instead using new money to keep itself from falling off its proverbial fiscal cliff. They added that its unwillingness to change is evident in the ballot measure’s language, which is vague enough to allow for non-classroom spending, such as paying off pension and health care debt and teacher raises. Opponents of the tax also worry about inadequate oversight of the new revenue and that hiking up costs for businesses could force them to raise service prices for consumers.

“We could give them $500 million a year or $5 billion a year, and they still have no plan on how to fix themselves,” VICA President Stuart Waldman said.

To prove accountability, the district’s school board voted unanimously Tuesday to create an “independent taxpayer oversight committee.” The committee would publicize how the district allocates revenue from the tax — which would charge local taxpayers 16 cents per square foot of developed property for 12 years if passed in the June 4 special election — and report progress in student achievement. L.A. Unified officials say this new revenue is vital for lowering class sizes and hiring more counselors and nurses as the district anticipates a $749 million shortfall below its required reserve levels by 2021-22. It’s at risk of a county takeover if it can’t prove its solvency in the coming months.

Those spearheading the “Vote No on Measure EE” campaign, the main opposition movement, understand that “the district is under a lot of financial pressure,” said Maria Salinas, president and CEO of the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce. But they’re unwilling to keep feeding a bad habit.

”By giving them money now, you are giving them the opportunity to make zero changes whatsoever,” Waldman said. “The only way they’re going to be forced to [change] is when they run out of money.”

Nick Melvoin, the school board vice president who consulted on the oversight committee resolution, called the opposition’s concerns “valid.” But he disagrees that the answer is withholding resources.

“To say we should wait unit there’s no money left … this isn’t a starve-the-beast scenario, because the collateral consequences are children,” he said. He added that some groups, such as the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce, initially supported a flat-rate version of the tax, making it clear that the opposition is largely motivated by financial interests. “Can I blame them for looking out for their interests? No,” he said. “Do I think that they still care about the district? Yes. But is this motivated by their bottom line and they just didn’t want to pay more? One hundred percent.”

The Vote No on EE campaign hopes to raise $4 million and has reported $658,120 in donations as of Wednesday, with $400,000 received last Friday alone, according to city ethics commission data. A Howard Jarvis Taxpayers Association committee is the lead donor thus far, at $245,000.

The Yes on EE campaign has drawn in about four times as much, with lead backers including United Teachers Los Angeles and L.A. Clippers chairman Steve Ballmer. Eli Broad, a philanthropist who supports charter schools, also donated $250,000 to back the measure (about 20 percent of the total annual revenue will go to charter schools within L.A. Unified boundaries). Mayor Eric Garcetti — a vocal proponent of the parcel tax who in January helped broker the $840 million teacher contract — highlighted the need for Measure EE in his State of the City speech on April 17.

“There will always be those who claim that funding our schools is a waste of money. But our children are not a waste of money,” Garcetti said in his speech.

Business and taxpayer advocates are adamant that the fight against this measure is not a fight against public education — it’s about ensuring the district is accountable before it takes more taxpayer money.

“I look at it from a pro-public education lens,” Salinas said. “If we do really want to make sure that those dollars are getting into the classroom … that should be [explicitly] in the measure. It is not in the measure today. And that’s where I think it’s important to ensure that our voters understand that.”

Stalling on reforms

While business advocates like the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce are taking a stand against the tax, Salinas says her organization has supported “many tax measures” that benefit students — including all five district construction bond measures in the past 22 years.

Those five bonds total $20.6 billion in loans to the district. Proposition 30, a statewide tax passed in 2012, generated about $700 million annually for L.A. Unified and was extended in 2016. The district also receives about $1 billion a year for high-needs student populations through the state school funding law enacted during the 2013-14 year.

Yet the district continues to project hundreds of millions in deficit spending. And achievement continues to lag: About 42 percent of students are proficient in English language arts, and 32 percent of students are proficient in math. Less than half of the class of 2019 are on track to be eligible for the state university systems, according to district data.

“That is terrible and unacceptable,” said Tracy Hernandez, founding CEO of L.A. County Business Federation (BizFed), whose two daughters went through the L.A. Unified school system. “No one should accept that. The district needs to institute reforms that change those educational outcomes.”

L.A. Unified did take on an ambitious “Close the Gap by 2023” initiative last June, which aims to make 100 percent of high school graduates eligible to apply to a state college by 2023. Melvoin added that the district has also been expanding data transparency with its Open Data Portal and is developing a School Performance Framework to better evaluate achievement and growth. District and union officials have repeatedly decried underfunding at the state level as a cause for stunted progress; California ranks 41st in the nation for per-pupil spending.

But even if more money materializes, executives say they see no surefire indication that reforms will come with it.

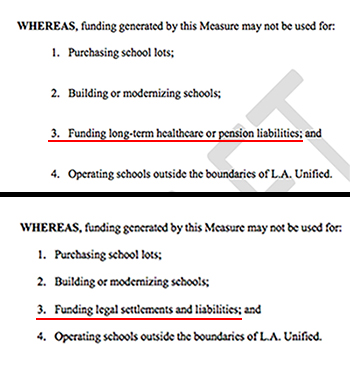

Waldman noted, for example, that a change in the final ballot language for the parcel tax weakens protections for classroom spending. Although a draft of the measure said the money couldn’t be spent on “funding long-term health care or pension liabilities,” the final language says “funding legal settlements and liabilities” instead. L.A. Unified owes $15.2 billion and counting in unfunded health care liabilities — promises made to retirees and future retirees to cover their health care bills — which HJTA president Jon Coupal deemed “the most concerning” financial issue gripping the district.

“Nick Melvoin has tried to rein in the extreme health care costs; he continues to get beaten back,” Waldman said. “Every member of the school district who’s been elected has talked about reforms. None of them have actually done it, and those who have tried have been beaten back.”

The reason for the language change is that “We have a pension and health care crisis that is going to require dollars from the district,” Melvoin said. “Until the board votes to reform it — and even when the board votes to reform it — there are still these promises made to employees that can’t disappear overnight. So there’s going to be some money that’s going to have to go to cover that. And whether that comes from the general fund or from the parcel tax … that’s just a reality.” But an oversight committee would report how much of the funds go to health care and pensions, giving the public a chance to react and respond, he said.

Superintendent Austin Beutner last fall was promising reform through a “re-imagining” plan, but he has yet to release it and has walked back some of its ambitions, including decentralizing the bureaucracy-heavy district into 32 autonomous networks, the L.A. Times reported.

Even after the district signed an $840 million teacher contract that it couldn’t afford in January, its budget and fiscal stabilization plan submitted to county overseers in mid-March was “very much the same” as the report it sent in December, Chief Financial Officer Scott Price told reporters. Meanwhile, outside experts have identified more than $236 million in annual savings if the district adopted their recommendations, LAist reported this week.

One of L.A. Unified’s largest cost-saving measures currently is $85.8 million in cuts to the central office over two years. But Waldman pointed out that District 6 board member Kelly Gonez asked finance officials at a March board meeting to look into whether “we can spare the local districts” from the office cuts “if some of these additional savings are realized.”

“That is indicative of a system that does not think they need to change,” Waldman said.

‘Like a heroin addict’

If the past is any indication, the parcel tax is not a slam dunk. A less costly parcel tax failed to pass in 2010, and the school board removed another from the ballot in 2012.

“The notion that ‘Oh, this time we promise if you give us the money we’ll change,’ I don’t think voters are going to buy that,” Coupal said.

A February poll on the heels of January’s teacher strike showed roughly 70 percent approval for a per-square-foot parcel tax, a hairline above the two-thirds vote required to pass. And at least two supporters of the tax — First 5 LA and the California Community Foundation — are BizFed members. The California Community Foundation agrees that “We need decisive action steps to realize the deep transformation necessary for the district to deliver the quality education our children deserve,” according to a statement. But it also believes that transformation requires some additional investment up front.

“First let’s establish a stable foundation of teachers along with additional counselors, school nurses, principals and important support staff,” the statement read. “A dedicated revenue stream is essential to help meet the mental, physical and academic needs of students.”

The district does appear to recognize a general distrust in its finances and the need for transparency. Tuesday’s approved resolution calls for nine “independent representatives” with “significant expertise” in areas such as academia, school finance and parent and family engagement.

This committee would “ensure the proceeds are used and distributed only for voter-approved purposes … are made publicly available, and that the District is held fiscally responsible,” the resolution language reads. The resolution adds that a representative could not be an L.A. Unified employee, official, vendor, contractor or consultant.

The extent of that independence, however, is murky. The amended resolution’s wording states that a nine-member panel would nominate those nine representatives; three of those nine panel members would be appointed by the school board itself or Mayor Garcetti. The nominations are also ultimately “subject to approval by the Board by a majority vote.”

That framework is “independent in the sense that you have an independent group of people — for the most part — selecting another independent group of people, and then doing oversight. You don’t have the board doing oversight of itself,” Melvoin said, adding, “There’s only so far you can go, because we’re also the elected trustees of the district, and have an obligation to our constituents. … It passes muster for me.”

The opposition is not placated.

The No on EE campaign called the vote “a panic-driven attempt to cover the fact that no accountability or transparency was included in Measure EE” in a statement Tuesday night.

“‘Independent’ oversight?” Coupal wrote in an email Friday prior to the vote. “You’re joking, right?”

“The board chose not to put an oversight committee in the ballot because that would have forced them to have real oversight,” Waldman also wrote in an email. He cited the Office of the Inspector General — L.A. Unified’s watchdog that closed five of its 95 pending cases last year — as proof of the current lackluster oversight measures in place. “This is fluff and they don’t actually have to do it.”

To Hernandez, the resolution is “just talk. It’s a real crying shame that they didn’t do it when they wrote the measure.”

Waldman offered up his own prescription.

“We just need LAUSD to recognize that they’re failing and that they’re willing to make changes to become better,” he said. “It’s like a heroin addict. They don’t think they have a problem, so they’re not going to show up for rehab.”

The trickle-down effect

Salinas and the L.A. Area Chamber of Commerce were behind the idea of a flat per-parcel rate if the district guaranteed that the funds had “strong” independent oversight. But when she saw the language for a per-square-footage tax without such assurance, the buck stopped there.

“For property owners and especially the housing property owners, [this tax] can create a real burden,” she said. “We’re already in a situation where affordability in the housing area is at crisis levels.”

Under the per-square-footage structure, most homeowners would pay between $100 and $450 per year. A 1,500-square-foot home would be taxed $240, for example. A 500,000-square-foot building, meanwhile, would be taxed $80,000. For renters, Measure EE would not interfere with existing or new rent stabilization ordinances. There would also be exemptions for senior citizens and those relying on disability payments.

Some parcel tax proponents believe it’s fair for larger property owners such as businesses to pay more, especially with 4 in 5 L.A. Unified students coming from low-income families. “At a time of record profits and tax breaks for businesses, these organizations opposed to Measure EE explicitly do not want to pay their fair share,” Yes on EE’s chief strategist Yusef Robb told EdSource. “They want the owner of a million-square-foot skyscraper to pay the same as the owner of a thousand-square-foot home.”

This sense of equity is what propelled District 6’s Gonez to vote for the more progressive option.

“I certainly take into account the feedback of all constituents, including the business community,” she wrote in an email. “Ultimately I decided with my colleagues that the square-footage approach was the most progressive option, given that commercial and residential property owners will contribute more equitably.”

BizFed’s Hernandez countered that businesses have to recoup that money and could raise the cost of services to do so, indirectly burdening all residents. A restaurant, for example, could have to raise the costs of food or “squeeze their employee base.”

“It’s not like free money that falls from the sky because they say they have businesses pay it,” Hernandez said. “There’s real effects on the costs of everything everyone buys and needs in everyday life.”

Coupal added that the tax could even prompt businesses to leave the area — or the state. California is infamous for being one of the highest-taxed states in the U.S.

“Look at the number of businesses that have bailed out of California because of its high tax and regulatory environment,” he said. “The list is legion.”

The dissonance has already contributed to tension. Hernandez last week claimed that Garcetti’s adviser, Measure EE campaign manager Rick Jacobs, was threatening to punish BizFed members backing the opposition, according to the L.A. Times. Jacobs denied it.

A Twitter account named “Bizfed Hurtskids” also emerged last month, claiming that the organization “doesn’t want your kids to have more teachers, nurses, and counselors.”

A Vote No on EE ballot statement on its way to residents’ inboxes this month has its own agenda. It reads, in all caps: “LAUSD WASTES OUR MONEY.”

‘We love being at the table’

Executives’ frustration with the parcel tax extends beyond the money and district accountability. They said they also feel left out of a process they wanted to be a part of.

A draft of the parcel tax was presented to the board on Tuesday, Feb. 26. A final version was unanimously approved two days later.

Salinas had read a statement of support for the flat-rate parcel tax at the Feb. 28 board meeting, highlighting her concerns with oversight. Waldman added that VICA, along with others, had asked board members in person and over the phone “to pull it off the ballot to work with the business community, the neighborhood councils, with community groups to come up with a consensus for the plan to make schools better, to raise funds to pay for schools, to find where there is bloat within LAUSD and make those cuts and make people feel better about investing.”

But “they chose to move forward with what we have now,” he said.

Melvoin acknowledged that the board moved at a faster pace than desired to meet deadlines for a June special election. If Measure EE passes in June, new tax revenue will start flowing into the district later this year.

If the businesses care about reform, “then get more involved in the school board election. Come to our board meetings, which I’ve never seen them at apart from the parcel tax. Come and talk to the board about what reforms you want,” Melvoin said. “Help a brother out.”

Business leaders say they’re eager and willing to work with the district to find a workable solution — after defeating the parcel tax.

“We love being at the table, being invited in,” Hernandez said. “And we’re happy to work with the district and others to find a good resolution that does bring the excellent education reforms we need to our school district.”

No reform at all is one of Hernandez’s biggest fears if this tax does pass.

“Without dedicated educational reforms that actually help the classrooms, help the teachers, help the kids have different learning outcomes … [my fear] is that [officials] will continue to feed the bloated bureaucracy,” she said. “I think our kids and our families get hurt the worst in the end.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)