Expanded Child Tax Credit Enshrined in Relief Bill Could Substantially Cut Poverty — and Lift Academic Performance

Updated 3/12

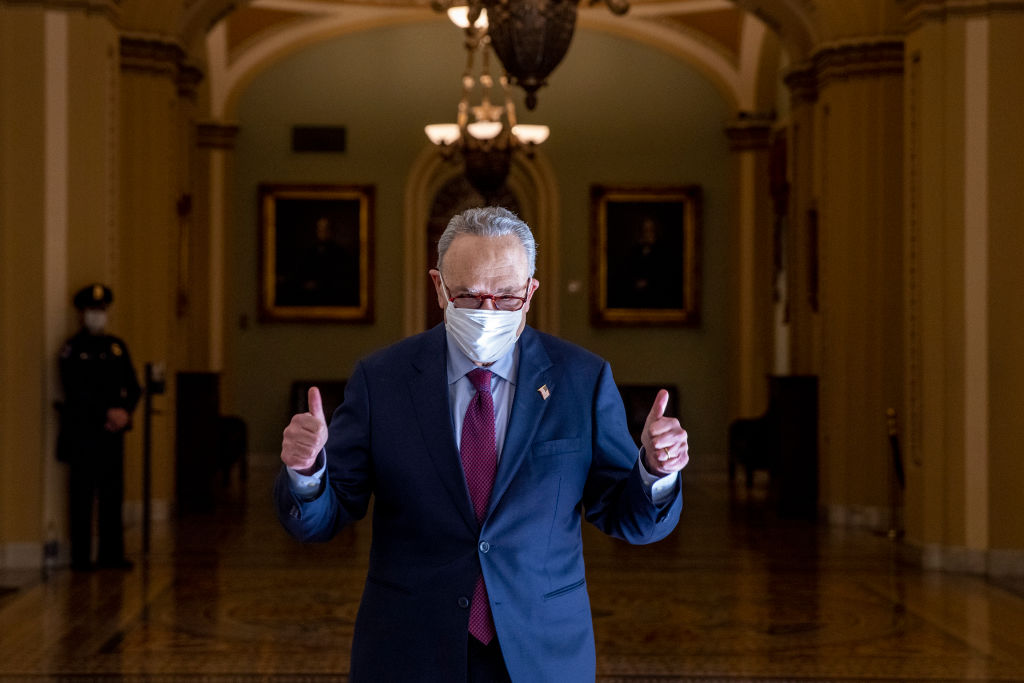

President Joe Biden signed the expanded child tax credit into law Thursday as part of the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. House and Senate voting on the bill fell almost entirely on party lines, with no Republicans in favor.

The House of Representatives is expected to approve the American Rescue Plan — the $1.9 trillion COVID relief package at the center of President Biden’s domestic agenda — on Tuesday. While education observers will celebrate the inclusion of billions of dollars in aid to schools, one of its tax provisions also holds indirect but monumental implications for American education.

The legislation would significantly expand the reach of the federal child tax credit during 2021 by increasing its maximum payout per child from $2,000 to $3,600, making it fully refundable (i.e., available in the form of cash if a parents’ tax liability is already at zero), and lifting the age of child eligibility from 16 to 17. It would also disperse payments to families throughout the year, effectively converting the credit into a kind of monthly child allowance program.

The cost of the proposal is around $110 billion. But for that price, Congress would be buying one of the most ambitious, if temporary, welfare reform experiments in history. By some estimates, it would cut the number of children living in poverty by nearly half, a reduction that is projected to increase their educational attainment and prospects for successful adult lives. It would also be available to families in the middle class, with two-parent families earning up to $150,000 receiving access to the full credit. Though not targeted specifically to K-12 schools, the expansion holds the potential of boosting students’ achievement and helping them finish high school.

Among wealthy, Western nations, the United States is somewhat rare in not making direct payments to families raising children. A slew of European nations including Norway, Germany, France, Ireland, Sweden, and the United Kingdom offer direct child allowances, while Australia, Japan, and South Korea provide similar benefits.

Greg Duncan, an economist at the University of California, Irvine, said that the U.S. has “always been a laggard” in supporting low-income families, a reality underscored by the business failures and mass layoffs of 2020. Researchers who regularly track household income have found that the economic damage inflicted by COVID-19 has pushed more families below the poverty line, even after accounting for the substantial assistance provided by previous relief bills.

“One argument is that as long as child poverty is quite extensive here — and it’s more extensive here than in other advanced countries — it’s…time to be thinking about a policy like a child allowance,” Duncan said. “I think the COVID economic complications reinforced that, but I don’t think that when the economy goes back to being more normal and high-growth that it would eliminate the need.”

Indeed, the idea of enhancing the existing child tax credit, or shifting it toward a full-on cash transfer, began gaining wider support in domestic policy circles long before the pandemic. The Republican tax cuts of 2017 expanded the credit from $1,000 to $2,000 through 2025, and Sen. Mitt Romney co-sponsored an allowance bill with Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet in late 2019. The flurry of new proposals seemed to reflect a recognition that millions of American families are struggling to meet the full costs of bringing up kids in an economy that can be chaotic even for those in the middle class.

Among the nation’s roughly 12 million children experiencing poverty, the challenge is especially acute. Irwin Garfinkel, a researcher on poverty at Columbia and a co-founder of the university’s Population Research Center, said that America’s lack of national infrastructure supporting low-income families was “entirely the reason” why child poverty rates are higher in the United States than in comparable countries. Along with several co-authors, Garfinkel has advocated for the passage of a child allowance along the lines of the Canadian Child Benefit, which was enacted in 2016 and has been associated with impressive poverty reductions.

“This is a matter of social policy,” he said. “If we want to, we can do this. Other rich nations have.”

How poverty affects schools

The near-ubiquity of child benefits in other countries is partly a recognition of an educational fact: Ample evidence suggests that poor children simply do not have access to the same learning opportunities that their wealthier peers do.

Schools with high concentrations of poor students, often located in large and majority-minority urban districts, perform dramatically worse on standardized tests, even when compared with schools with similar racial profiles. Nationwide data collected by Stanford sociologist Sean Reardon strongly suggests that large achievement gaps between white and minority students are overwhelmingly driven by the concentration of poverty in schools that enroll large numbers of Hispanics and African Americans. In one study, children from the bottom fifth of the national income distribution were found to be five times more likely to drop out of school than those from the top fifth.

But perhaps the most persuasive illustration of poverty’s impact on K-12 outcomes is offered by successful attempts to reduce it. In 2019, the National Academy of Sciences released a mammoth report examining the state of child poverty in America and the most promising means of curbing it. Part of the effort included looking at existing programs supporting the poor, including the Earned Income Tax Credit, Temporary Aid for Needy Families (our most prominent existing cash transfer program), Medicaid, and other initiatives. The panel’s conclusion was that the effects of low income levels — even independent of associated conditions like living in a single-parent family — were clearly detrimental to children’s physical, mental, and emotional well-being, and that poverty-reducing programs tended to mitigate those effects.

With several other researchers, Garfinkel undertook a similar analysis to judge the costs and benefits of adopting a child allowance, gathering 20 high-quality studies of direct cash and near-cash provisions to needy families. The impacts were both large and varied, he said.

“There are effects on birth weight, on neonatal mortality, on child health between the ages of one and death, on longevity of children as adults — 19 of the 20 studies find positive effects,” Garfinkel said. “Children, because they’re healthier, get more education, earn more as adults, pay more in taxes, [have] less involvement in protective services and the criminal justice system.” In total, he found, a $100 billion expansion would generate up to $800 billion in value each year.

That said, programs that directly benefit the poor have typically proven to be politically vulnerable. New York University professor J. Lawrence Aber told The 74 that much of public discourse around welfare spending was “filled with fears” that recipients would squander their benefits on drugs. In reality, he said, they were much more likely to spend them on food, shelter, and educational costs.

“Most families that are struggling economically really want nothing more than for their children to succeed, and that aspiration is voiced and exercised by making investments in their education,” Aber argued. “The vast majority of parents say, ‘I’m investing everything I can, short of starving them or freezing them.'”

But the child tax credit as presently constructed denies its full benefits to millions of low-income Americans. Ultra-poor families making less than $2,500 per year, who would likely benefit the most receive no portion of the $2,000 credit because its value exceeds what they owe in federal tax; those making less than $12,000 cannot receive its refundable value of $1,400. A research study circulated in October found that the “vast majority” of households in the bottom 10 percent of the U.S. income distribution are ineligible, while nearly all households in the top half are.

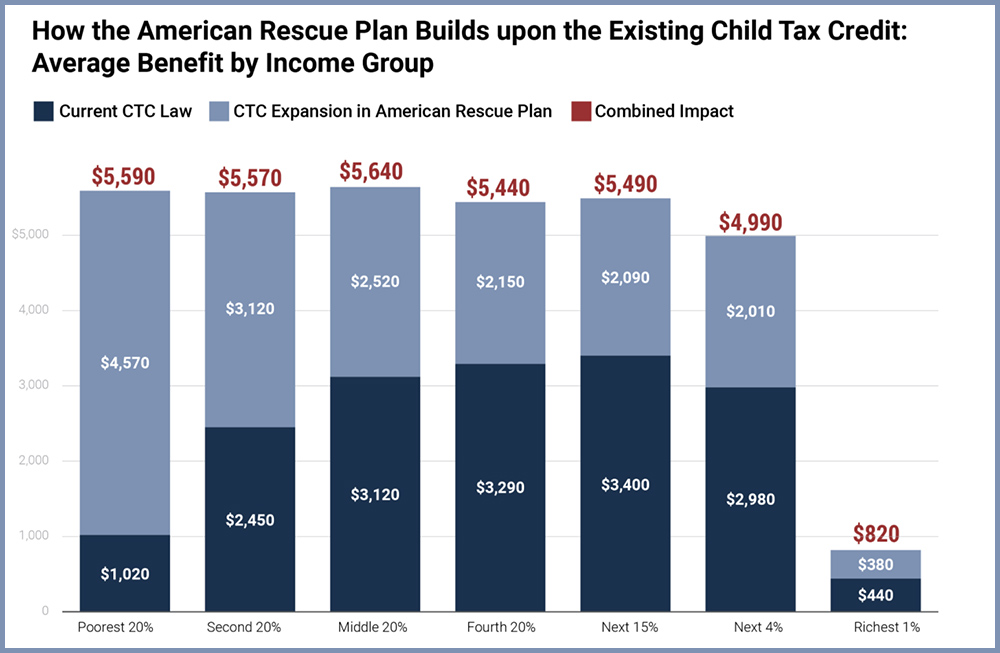

By contrast, an analysis released in January by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that Biden’s expanded credit would increase the average benefit to the poorest 20 percent of families from a little over $1,000 to nearly $5,600. Irvine’s Duncan said that the proposed adoption of a child allowance would, in effect, merely extend the benefits of the current policy to those who currently go without it.

“We’ve been doing it for 20 years in the form of the child tax credit,” Duncan said. “I tell people, ‘We already have a child allowance…So don’t tell me this is a new thing, because we’ve had a child allowance all along. And we don’t worry about middle-class moms spending the money on gym memberships.”

The Romney proposal

The last year, in which the government spent trillions of dollars shoring up Americans whose livelihoods were imperiled by the pandemic’s disruptions, provided an imperfect preview of what direct cash transfers might look like. In the absence of direct $1,200 stimulus checks and enhanced unemployment benefits, the deprivation would have been far worse, said Aber.

“Minus government assistance, the loss in earnings and work would be having a very, very significant negative impact on families,” he said. “We didn’t have a child allowance in place, but we did enact those [emergency measures]. If we had a child allowance, those heroic efforts wouldn’t be necessary to guarantee some level of support for kids even though their parents are losing income. It is, in that sense, a safety net.”

The American Rescue Plan is the latest of the mammoth relief packages to pass through Congress, and the Senate’s version is likely to land on President Biden’s desk by mid-week with a one-year expansion of the child tax credit included. But that proposal, though favored by the president, is not the only one making the rounds in Senate offices.

At the beginning of February, Mitt Romney released his own child allowance legislation. Substantially similar to the Biden administration’s, it is in some respects even more generous: It would set payments at $350 per month for the youngest children (the Democratic proposal only hits $300) and begin them at the third trimester of a mother’s pregnancy. Even more importantly, it is designed to be permanent, rather than disappearing after one year.

The Democrats’ built-in expiration date is already regarded with suspicion by Republicans, many of whom believe that the party will act next year to push the newly reformulated credit into the future rather than make families accept a de facto tax increase. But if they do, they’ll have to find a way to pay for it going forward. Romney’s bill does so mostly by eliminating or reorganizing other benefits, such as the deduction for state and local taxes and the cash transfer known as Temporary Aid for Needy Families.

That idea doesn’t sit well with progressive defenders of those expenditures, the bulk of whom would rather add a child allowance atop the status quo. Aber said that the Romney plan was a serious counterproposal with aspects that could be helpfully incorporated into future bipartisan overhauls. He also added that it was “generous” to call it a GOP proposal, given how few of Romney’s fellow Republicans are likely to join him.

“At the level of principle, I would trade some benefits for making it permanent and making it sustainable because you have a realistic financial package,” he said. “But I also can’t refrain from thinking sensible things about kids, and from that point of view — boy, I’d love to get this sucker passed and get some relief for the poorest families.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)