Exclusive: Over 80% of Women Leaders in Education Experience Bias, Survey Shows

One leader quoted in the first-of-its-kind report said she was told to wear a skirt instead of pants so she didn’t “come off as intimidating.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

At 5 feet tall, Uyen Tieu doesn’t tower over anyone, including many students. So when a superior said she was too petite to be anything but an elementary school principal, she figured he was probably right.

“I accepted it, because I didn’t know any better,” said Tieu, who didn’t find encouragement from her own Vietnamese family either. “My father was like, ‘Oh, I’m so surprised that they selected you to be the principal.’ ”

A decade later, Tieu has not only been an assistant principal and principal, she’s now in charge of student support services for the Houston Independent School District — the eighth-largest school system in the U.S. But as an Asian woman and a single mother, she still feels pressure to prove herself in a male-dominated field.

“I spend double the time to make sure that everything I produce is 100% — nothing less,” she said.

The comment about Tieu’s height — and job prospects — is among the anecdotes district and state leaders shared as part of a first-of-its-kind survey of women serving in high-level school positions. Conducted by Women Leading Ed, a 300-member national network, the results show that despite ascending to senior roles in school systems and state departments, the vast majority of female leaders experience bias and think often about quitting. Over 80% of the 110 women who responded, from 27 states, said they feel they have to watch how they dress, speak and act because they are in the spotlight as senior leaders.

“I have found myself in high-powered meetings where men in leadership roles do not even look at me, but instead address my male colleagues,” said Angélica Infante-Green, Rhode Island education commissioner and a Women Leading Ed board member. “In a world where traditional notions of leadership have been predominantly shaped by men, there exists a profound need for diversity in representation.”

The survey, one expert said, comes at a time when districts could benefit from strengths many women bring to the table.

“Women who come up through this pipeline have often been elementary school principals and that sometimes precludes them from being selected as superintendents,” said Rachel White, a University of Tennessee, Knoxville, assistant professor. She launched The Superintendent Lab, a research center, last summer to improve data collection on school system leaders. It’s common, she said, for school boards to view high school principals, who are predominantly men, as more authoritarian or to prefer someone with a background in finance. “The type of leadership we need right now around family and student engagement and curriculum and instruction — elementary school principals really get that right.”

But many women leaders say they face a double standard.

“When a man in leadership takes time to coach his child’s sports team, he is applauded,” Infante-Green said. “If I choose to attend my daughter’s dance recital over a meeting, I am judged much differently.”

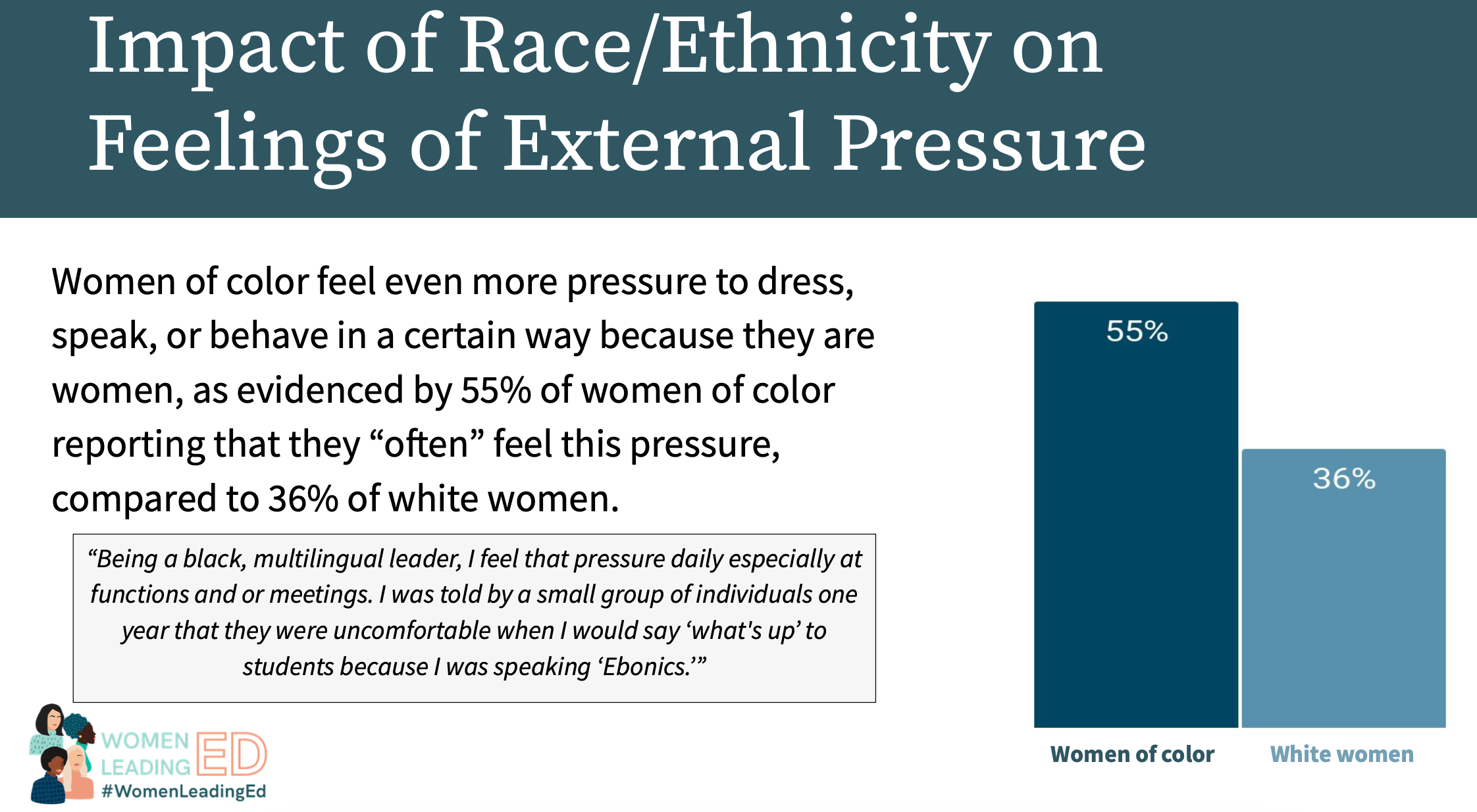

One leader quoted in the report said she was told to wear a skirt instead of pants to a presentation so she didn’t “come off as intimidating.” Black, Hispanic and Asian-American women were even more likely to feel pressure related to their behavior — 55%, compared with 36% for white women. One Black leader’s colleagues said the way she greeted students with “What’s up” made them uncomfortable because she was “speaking Ebonics.”

Tieu, in Houston, said students are often surprised to see a minority woman, especially an Asian woman, in leadership.

“I want to show these young ladies that there’s nothing wrong with having aspirations,” she said. “There are going to be moments in time when you have to overcome barriers, but be smart and learn from it.”

The survey results build on the Superintendent Research Project conducted by ILO Group, a women-owned firm focused on education policy and leadership. Nationally, over 20% of the nation’s 500 largest school districts saw turnover at the top, according to the 2023 results. Among women, the rate was slightly higher — 26%.

The most recent analysis also showed that even with a modest increase in the number appointed to superintendent positions, women still represent less than a third of those leading school districts. Women, however, make up 80% of the teacher workforce and more than half of school principals.

Julia Rafal-Baer, CEO of Women Leading Ed and ILO, called it a “glass cliff,” and said when women reach higher ranks, they“nearly universally experience bias that impacts their ability to do their job, how they feel about their work and their overall well-being.”

Sixty percent of women leaders said they think about quitting due to stress, and of those, three-quarters said they contemplate leaving on a daily, weekly or monthly basis.

Loren Widmer, director of student services for the Affton School District, outside St. Louis, left a neighboring system after unsuccessful efforts to advance into administration.

“I really felt like the only potential way to move ahead in that district was to be part of the good old boys club,” she said. “If you didn’t go to school there, play on the football team and come up through the ranks, there was no chance that you would progress.”

That became clear to her in 2017 when she was in line for an assistant principal job. The district offered her a 9 a.m. interview on a Friday, the same morning she was scheduled to have a C-section. She asked for an alternative time — even a virtual interview at noon the same day of her son’s birth — but the official turned her down. The position later went to a man.

‘Among all these men’

The new survey follows a recent thread that Rafal-Baer initiated on LinkedIn, asking women leaders to share some of the worst comments they’ve heard along their “professional journey.” Some of the nation’s top education leaders weighed in.

“A … colleague said (in front of the others), ‘You must be really proud to be the only woman among all these men,’ and then squeezed my shoulder a little longer than anyone needed,“ recalled Carolyne Quintana, a deputy chancellor for the New York City schools.

Lesley Muldoon, executive director of the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees the National Assessment of Educational Progress, shared a comment she heard as a new mom.

“An older male colleague bitterly complained he wished he’d gotten a three-month vacation after I got back from a horrible, miserable, painful maternity leave,” she wrote.

And Daylene Long, CEO of a STEM education company, posted that someone told her, “Being competitive is not an attractive trait in a woman.”

‘You don’t have to choose’

But some leaders also see signs of progress.

In Affton, Widmer’s district, half of the top-level staff and four of the five principals are women. She thinks the support women feel contributes to the district’s stability.

“You don’t have to choose between staying home with your sick kids or leading a department,” Widmer said. “You can do both.”

And in the early months of the pandemic, Infante-Green participated in daily press briefings with then-Gov. Gina Raimondo and Dr. Nicole Alexander-Scott, the former state health director. A mother even sent the commissioner a card with Superwoman on it as a thank you for inspiring her daughter.

“In that moment, it dawned on me that our presence together at those news conferences was more than just symbolic; it was a powerful statement of solidarity and resilience,” she said. “It sent a positive message that in Rhode Island, leadership knows no gender boundaries.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)