Exclusive: Analysis — How 18 Top Charter School Networks Are Refining Remote Learning for the Fall

Last spring, some of the nation’s most prominent charter networks quickly rolled out remote learning after school closures, including mechanisms that monitored students’ academic progress and gave them access to live lessons. This fast response may have put these charter schools in a strong position to serve students and families remotely this fall.

Our latest review of reopening plans for 18 leading charter school organizations shows they are strengthening curriculum offerings and modifying schedules to better serve students — although their plans are less detailed than districts’ on remote learning improvements or lessons learned from the spring. They are also not addressing some critical issues facing students and families.

Our database includes 18 charter management organizations (CMOs) that are part of the Charter School Growth Fund portfolio and comprise 10 or more schools. These are large, high-profile, nonprofit organizations that serve large numbers of kids and are generally well regarded for their ability to lift student achievement and close opportunity gaps.

Last spring, these CMOs held real-time online classes, checked in regularly with their students and graded work more quickly than districts.

Within three weeks of school closures, 44 percent had established comprehensive remote learning plans that included access to formal curriculum, instruction and progress monitoring. By the end of May, 78 percent of the CMOs reviewed were doing this. By contrast, the numbers for 86 districts we reviewed in the spring were just 13 percent and 61 percent. These features now appear to be the norm for almost all school systems, as districts have sought to improve remote learning.

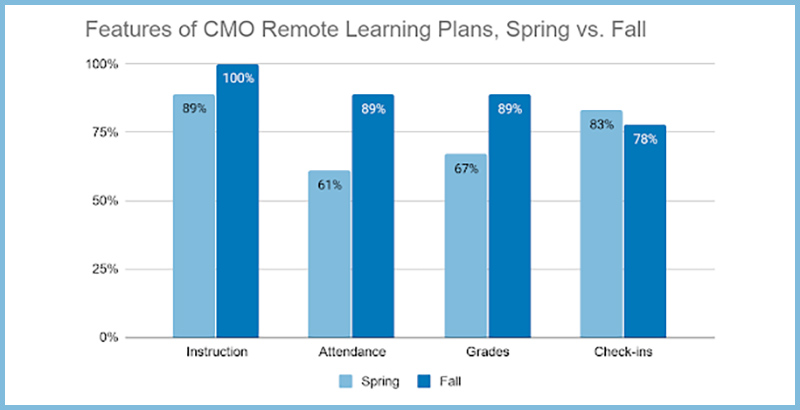

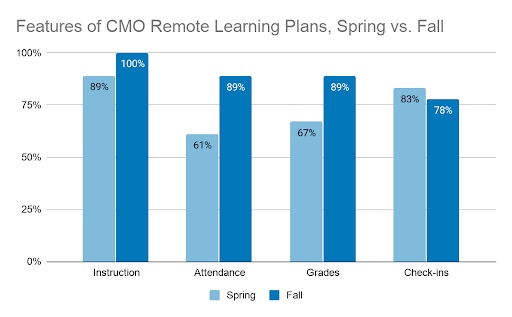

This fall, CMOs are even more likely to expect teachers to deliver instruction, grade student work and track attendance than they were in the spring.

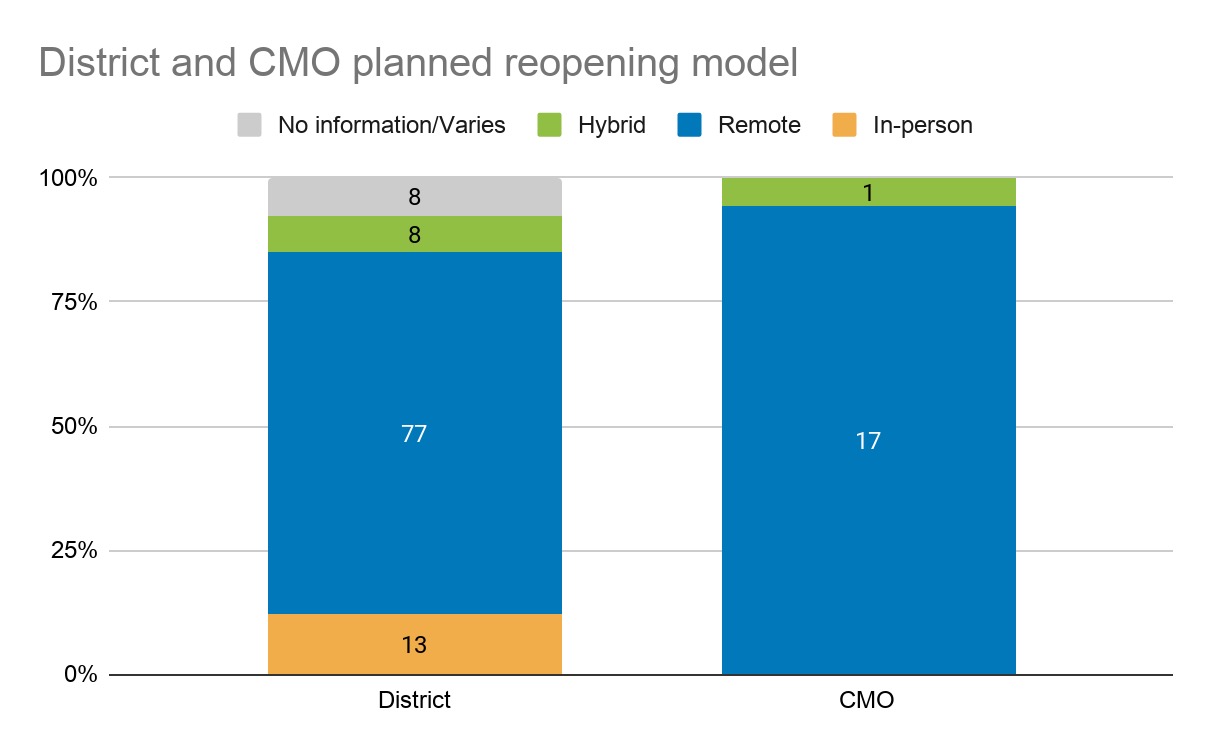

In fact, the 18 CMOs have been far more likely than districts to choose remote learning. Ninety-four percent (17 of 18 CMOs) have already started the school year with all-remote learning.

Some of the CMOs are changing their curriculum to provide a more comprehensive experience for students.

Chicago’s Noble Network, for example, published a plan focused on accelerating learning to make up for any gaps in instruction this spring. Noble cites research that “students achieve at higher rates when they are exposed to grade-appropriate work rather than remedial work.” It plans to roll out network-level resources that help teachers diagnose learning loss and incorporate the teaching of missed skills into new and ongoing lessons rather than focusing on remediation as a separate unit.

Students in Uncommon Schools, a network with schools across the Northeast, will continue engaging in extracurricular activities, including projects and clubs like speech, debate and robotics. These projects will be fully remote and led by a combination of teachers and outside experts in their fields. Because they will be online, some projects will be cross-campus, meaning students will have the opportunity to join with other Uncommon students from other cities and states.

KIPP SoCal will offer its afterschool program virtually through Google Classroom, featuring art, dance, fitness, yoga, science and other enrichments. Denver’s DSST Public Schools is sending home science materials so students can do their own experiments, guided by teachers through live videoconferencing, and is offering opt-in humanities and science courses that will be taught networkwide.

The CMOs in our spring review were quick to move to online learning — 14 of the 18 (78 percent) were providing instruction, and seven (39 percent) offered real-time teaching on schedules that closely mirrored the regular school day.

Although the CMOs we reviewed do not appear to have drastically changed their curricular, instructional or progress monitoring approaches since spring, they have tweaked scheduling, perhaps as a result of student and family feedback. This fall, 15 of the 18 (83 percent) plan to provide a combination of live instruction and assignments/prerecorded instruction in which students work independently — a recognition that students may benefit from both.

The Noble Network has made it a priority to provide both recorded and real-time instruction, recognizing that some students might not be able to participate in real-time classes on schedules set by their schools. Schools in the network may provide real-time sessions for students to connect with their teachers and peers, to help build stronger relationships and ensure that students grasp the material they’re being taught. But these are optional and do not affect grades.

Great Hearts Academies, an Arizona- and Texas-based charter network focused on classical education, applies a different rationale. It says its fall model “will not be one of independent work with occasional teacher interaction; it will be one of regular online instruction and contact with teachers and peers at their school, supported by independent work. The new [model] is not homeschooling; it is, rather, school at home.”

Some CMOs are building independent student work time into their schedules, which can also give teachers time to collaborate and plan.

Texas-based Uplift Education, for example, plans to set aside afternoons for this purpose. Houston-based YES Prep has adjusted schedules for K-2 students, adding more small-group work and screen time breaks.

KIPP NYC is building a library of lessons, recorded by veteran teachers, that will be available to students on demand to supplement live videoconferences with their teachers and self-paced work that allows “for independent thinking and research.” The CMO also plans to hire a family resources support manager to help with remote learning.

Only 6 of the 18 (33 percent) CMOs prioritize certain groups of students for in-person instruction, compared with 42 percent of districts we reviewed (45 of 106). Only seven (39 percent) clearly articulate how they plan to provide interventions to catch students up and accelerate learning, versus 38 percent of districts (40 of 106). Success Academy, in New York City, identified students who will have intervention time on half-day Wednesdays, and the network plans to have dedicated on-campus time for students who need additional academic support.

Some CMOs, such as Summit Public Schools, a personalized-learning-focused charter network on the West Coast, New Orleans’s homegrown InspireNOLA and Great Hearts Academies are thinking flexibly about their physical space, creating supervised internet learning hubs where students will have a desk and access to the internet for online learning. At Great Hearts, these are large multi-age groups in multi-purpose rooms, hosted at select schools for any student in the network.

DSST says some teachers may invite students to participate in small, voluntary, in-person activities during the fall. Following local public health guidance, these meetings will occur outside, potentially off-campus, and be limited to 10 to 15 students.

Still, the CMO plans we reviewed lack information about some key issues that will impact students over the longer run. Only 5 of the 18, or 28 percent, said they plan to diagnose student learning loss when school resumes. Only half detail parent training on remote learning, similar to the percentage of 106 districts we reviewed. Districts and CMO reopening plans also do not provide much detail on special education or other vulnerable populations. Just 7 of the 11, or 61 percent, publicly make mention of special education.

Five of the CMOs in our review are part of the KIPP family of schools. The national organization made headlines this summer when it announced a suite of changes, including the elimination of its slogan, “Work Hard. Be Nice,” a reduction of on-campus police officers, and a review of inequitable student discipline practices.

However, only one other CMO in our review, Uncommon, explicitly outlines how its fall plan will address racial equity. Four highlight it as a call to action or frame for making decisions. Because overcoming the opportunity gap is a key part of these CMOs’ mission statements, they have an opportunity to lead the field here with explicit acknowledgement of racial equity and specific actions for addressing it as schools resume.

The question CMOs, like all school systems, now face is how to address new challenges — from the possibility they will be vacillating between remote and in-person learning as public health conditions shift, to the need to accelerate student learning and address gaps that likely emerged over the spring and summer. We see signs of promising practices, but also missed opportunities to better communicate their plans and to lead all public schools in rising to this unprecedented challenge.

Sean Gill is a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at the University of Washington Bothell. Lanya (Lane) McKittrick is a research analyst at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, where she works on projects related to special education and families.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)