Even After Colorado’s Teacher Evaluation ‘Revolution,’ Fewer Than One in 1,000 Rated Ineffective

“The impact of teachers and leaders is so dramatically different than the rest of the reforms we talk about that, literally, things like class size and curriculum and professional development plans are minuscule in comparison to the impact of great teachers and leaders,” Michael Johnston, the bill’s chief sponsor and then a state senator, said at the time.

“The message that we, the almighty legislature, is giving to one of the hardest-working professions I know is to ‘just work a little harder and maybe we’ll let you keep your job,’ ” state Sen. Nancy Todd said, speaking against the bill.

As a Denver Post story put it at the time, “The bill signals an education revolution in Colorado.”

But now, years later — after controversy, a “state council for educator effectiveness,” implementation across the state, and faded media attention — some of the results are in, and they don’t seem revolutionary.

Just .09 percent — fewer than one in a thousand — of Colorado’s roughly 50,000 teachers were rated “ineffective” under the law in the 2014–15 school year, according to data recently released by the Colorado Department of Education. Nearly 4 percent of teachers scored “partially effective."

Not surprisingly, the evaluation law does not seem to have caused a large number of tenured teachers to be fired — as some supporters hoped and critics feared — at least in several of the state’s largest districts, according to data obtained by The 74 through public records requests.

Meanwhile, some of the law’s ardent backers have rethought their position. Roaring Forks schools superintendent Rob Stein, who testified in favor of the bill, said his views have changed dramatically.

“Broadly speaking, I would say the law has been a failure,” Stein told The 74. “We have not realized the improvements that we hoped to see, and it’s just added another layer of bureaucracy and hoops.”

On the other other hand, Kerrie Dallman, the head of the Colorado Education Association — the state’s largest teachers union and chief opponent of the law in 2010 — praised aspects of the new evaluation system, saying it helps teachers understand the expectations for performance and has led to better feedback on how to improve.

The experience of Colorado highlights the national disenchantment, by some, over the rapid drive to implement new teacher evaluation systems that were supposed to fundamentally reshape the teaching profession, as well as the difficulty in determining how successful that push has been.

Colorado’s 2010 law was spurred partly by the Obama administration’s economic stimulus plan and its $4.35 billion Race to the Top initiative. Cash-strapped states were offered the chance to compete for federal dollars based on adherence to a set of favored reforms, including more rigorous evaluation systems that linked student test scores to teacher performance.

The Colorado bill featured emotional debate and passed with unanimous support among Republicans, as well many crossover Democrats; it was even backed by American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, whose union has only a small presence in the state. The bill was was signed into law by the state’s Democratic governor.

The law based 50 percent of teachers’ ratings on student test scores, with the other half based largely on classroom observations; teachers with two consecutive below-average ratings could lose tenure, though this wouldn’t start applying until the 2014–15 school year. New teachers would receive tenure with three consecutive effective or better ratings.

Part of the impetus of the approach in Colorado and elsewhere was an influential 2009 report, known as “The Widget Effect,” which found that in several districts little effort was made to evaluate teachers or differentiate between those who were more or less effective.

“There was a deep, sincere desire to create an evaluation that was meaningful so that teachers could get the kind of individualized support and get useful feedback,” said Van Schoales, head of the reform group A+ Colorado. “Some folks were focused on getting rid of the worst teachers; others were focused on differentiating the level of quality so folks could get better.”

That’s why it’s been so disappointing to some that Colorado’s new system has replicated the widget effect to a large extent.

“It remains unclear whether [the law] is living up to the original ideals as far as having objective measures for teacher effectiveness while providing more differentiated support for teachers,” Schoales wrote in a recent blog post following the release of evaluation scores.

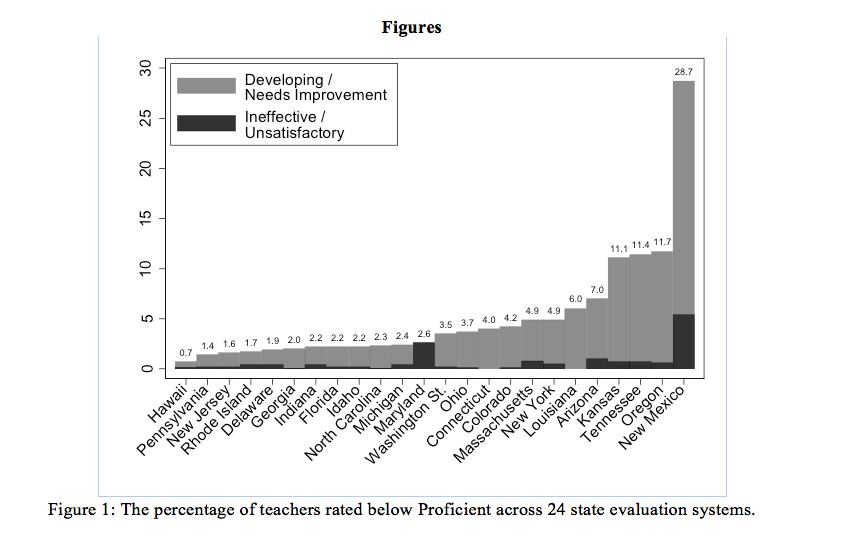

Matt Kraft, a researcher at Brown University, says Colorado is hardly unique in this regard, even relative to other states that have implemented new evaluation systems. Kraft’s recent study, appropriately titled “Revisiting the Widget Effect,” finds that the vast majority of teachers are still rated good or great under the new systems.

Source: “Revisiting the Widget Effect”

Combining the number of teachers who are rated partially effective and ineffective, Colorado is similar to other states; but when just considering those teachers judged ineffective, Colorado has significantly fewer.

Kraft says this is a concern, but not the whole picture. “Do evaluation ratings have to shift dramatically in order to drive instructional improvement and change?” Kraft said. “I would argue the answer is no, though it’s one avenue.”

Most states are identifying more teachers as less than effective than under old systems — about 3 percent now, versus 1 percent previously.

In several of Colorado’s largest school districts, only a handful of teachers have been formally dismissed, according to responses to public records obtained by The 74.

Denver Public Schools has formally terminated eight teachers since 2010. In suburban Denver districts, the numbers look similar. The Cherry Creek School District has fired one teacher total since then and the Adams County school district has dismissed five. Jefferson County has fired four teachers since 2014. Douglas County, which is between Denver and Colorado Springs, has dismissed six teachers since 2014.

There did not appear to be clear upticks in dismissals over time across the districts, though higher stakes — including potential loss of tenure — have only just recently begun to kick in.

The numbers include tenured teachers formally dismissed, as well as non-tenured teachers fired mid-year. They do not account for untenured teachers who were not renewed between school years or teachers who left voluntarily, including those under threat of dismissal or counseled out for performance reasons.

Kraft argues that an even more important question than how many teachers get low ratings or are dismissed is whether the evaluation system is leading to changes in how teachers teach.

“Are there meaningful conversations about instruction happening? In my mind, that is how you improve practice,” he said. “If the rating didn't change and no one's talking about instruction, I would be very pessimistic.”

Research from Kraft and others shows that principals believe more teachers are low performing than the number they actually rate as such. Kraft surveyed principals in one urban district and found that although principals believed that nearly one in five teachers performed below proficient, only about 6 percent were rated that way.

Similarly, a study of Miami-Dade County schools found that principals gave teachers much better ratings on a high-stakes evaluation as opposed to their low-stakes survey responses.

Kraft’s study asked principals to explain this disconnect, and they offered a variety of reasons: a lack of time to document low performance, a desire to allow teachers to improve without the specter of a negative rating, personal discomfort with providing a low rating, and an inability to remove or replace a struggling teacher.

The inclusion of student test scores was also designed to create a greater spread of ratings, but it generally hasn’t worked out that way. Many teachers in Colorado are judged by what’s known as “student learning objectives,” in which teachers set goals for student performance based on a test those same teachers design, administer, and grade. Across the country, this has generally led to high evaluation marks.

“I think we put too much value in the [student] growth metrics being valid and powerful,” said Schoales. “At least I personally now have regrets around that.”

Stein, the Roaring Forks schools chief, says the 18-page evaluation rubric proved more of a hindrance than a help.

“The state of Colorado developed through a consensus process a very cumbersome set of rubrics for evaluating teachers,” he said. “What I hear from teachers and principals [is that] there are so many elements that it’s become a check-box thing rather than a real opportunity for conversation about improving practice.”

Stein also says that the scoring system creates a “Lake Wobegon effect,” in which, based on how the rubric is scored, the vast majority of teachers will be considered effective or better. Stein isn’t sure why that is the case, but he said, “I suspect it has to do with [a] consensus of stakeholder groups pushing very hard to keep the scoring light.”

Mark Sass, a part-time high school teacher in suburban Denver’s Adams County and policy director for the Colorado chapter of the reform-minded teachers’ group Teach Plus, agreed that there are problems with the rubric.

“The implementation has been difficult,” said Sass, who testified in favor of the law in 2010. “There was an attempt by the state to put together a general framework … and it ended up being incredibly cumbersome, complex, and too much work.”

Mary Bivens of the Colorado Department of Education notes that there is currently an effort to slim down the rubric by reducing the number of performance elements from 26 to 17.

The .09 percent ineffective number is a little more complicated than it seems at first glance. Because of how districts report all ratings to the state, explained Bivens, the numbers only include teachers who remain the following school year. Left out are those who leave the district voluntarily or are fired. If more low-performing teachers are among those departing, which seems likely, this would understate the true proportion of educators rated ineffective.

What’s more, in the 2014–15 school year — the first year the new evaluation could count toward losing tenure — districts could exercise a one-year grace period where they could reduce the role of student test scores (even to zero percent) in the final evaluation, meaning teachers would be graded more on classroom observations. Bivens said about half of the state’s districts took advantage of this flexibility, which was instituted while the state transitioned to new Common Core–aligned tests. (Because of how the districts report information to the state, the Colorado Department of Education said results from 2015–16, when test scores had to be included for the first time, are not yet available.)

Dallman, of the state teachers unions, says she’s not particularly concerned that so few teachers got low marks.

“As a profession, we have a bar for entry,” she said, pointing to greater student-teaching requirements. “As those standards for entry have increased, we’re seeing better candidates enter the profession.”

Dallman says the benefits of the evaluation system have come from a focus on setting expectations and helping teachers improve.

“What I believe we achieved with the state model evaluation system was a rubric that really provides quality, actionable feedback to teachers,” said Dallman, who sat on the task force that designed a model system that districts could adopt. “It really creates a road map of success — teachers know exactly what’s expected of them, they know what they’re expected to demonstrate.”

Research suggests that evaluations can have a positive effect even without major differentiation in ratings or a high-stakes approach. A study of a low-stakes Chicago pilot evaluation program found that it improved student achievement and caused low-performing teachers to leave. Similarly, research in Cincinnati found that evaluated teachers improved in the subsequent year.

On the other hand, Washington D.C.’s high-stakes evaluation system led some struggling teachers to quit on their own and others to improve, likely resulting in improved student achievement. A study of Houston, though, found that the city’s evaluation approach did not lead to noticeable gains in student achievement and may have caused higher turnover rates among teachers.

Tom Boasberg, superintendent of the Denver Public Schools, recently told The 74 that the implementation of the evaluation law has gone “very well, but far from perfectly.”

“We really emphasized from the beginning that the system was much more about coaching and support and learning and growth than it was about evaluation,” he said.

Preliminary research has found that since 2009, Denver schools have seen increases in retention of among the most effective teachers as well as decreases among lower-performing teachers.

There do not appear to be any studies to date linking the state’s teacher evaluation system to student outcomes.

Johnston, the former Colorado state senator who spearheaded the evaluation law, is now running for governor. He did not respond to multiple requests to comment but in a previous interview told the The 74, “One of the wise decisions we made during the passage of our legislation was to create time for design, as well as implementation on this massive of a change, because when you're talking about completely redesigning the way every teacher and principal in the entire state is evaluated — and doing it at the same time that you’re redesigning all the state standards and all the state assessments — you want to try to do that in a deliberate way.”

If Johnston becomes governor — he faces a hotly contested primary, and, if he survives that, the general election — the law will probably be safe. But there have been a number of efforts to roll it back. One bill, backed by the teachers union and several Democratic legislators, would have permanently and significantly reduced the role testing played in teachers’ ratings and would require teachers previously rated effective or highly effective to be evaluated only every three years rather than annually. The proposal was defeated in committee last year.

“For the first time in a lot of districts and a lot of schools, teachers and principals are having hard and honest conversations about what do we expect kids to know and be able to do when the semester's over and how will we know if they can do that,” said Johnston in 2015.

It’s tough to measure the success of the law objectively, though no one seems to be claiming it had the dramatic effect that many hoped for back in 2010. Naturally, different stakeholders have different prescriptions for how to improve it. Dallman wants to reduce the role of testing; Stein says the rubric is too cumbersome; Boasberg argues there needs to be more room for subjectivity and professional judgment. Colorado, like other states, has more flexibility with the passage of the Every Student Succeeds Act, which prohibits the federal government from pushing certain evaluation approaches.

Whether the law changes remains to be seen. Whatever the case, Colorado won’t be alone in grappling with the challenges and complexities of evaluating teachers.

“Improvement takes time and sustained investments,” said Kraft, the Brown researcher. “Deciding now that it’s a failure would be premature.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)