Enrollment Equity: New Report Urges Policymakers to Push Charter Schools to Welcome More Midyear Transfer Students

Students who transfer schools midyear in Washington, D.C., are much more likely to end up in a traditional neighborhood district school than in one of the city’s public charter schools or a citywide or selective-enrollment district school, according to a new report by the Center for American Progress.

This is significant because midyear turnover can be damaging both to students who leave their schools, whether because of a move, instability at home, expulsion or another problem — and to the schools that accept them. A move can be positive if a student ultimately ends up in a higher-performing school, but many schools limit backfill — the placement of a new student in a seat vacated by another — to the start of the school year or to certain transitional grades.

When backfill rates are dramatically higher in one kind of school, the disproportionate level of churn is inequitable for the students and compounds the challenges faced by the schools that accept large numbers of highly mobile students, the report argues. On the other hand, among other justifications for limiting backfill, educators frequently credit a strong school culture — often cemented in the first months of the academic year — as contributing to their high performance.

Building on examinations by the The Century Foundation and the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools of backfill policies and practices nationwide, the CAP researchers examined enrollment data for schools in Washington, D.C. The district’s unified enrollment system, which assign its 93,000 students to both traditional and charter schools, makes it possible to track midyear student exits and entrances.

Using averages, they found that for every 500 students enrolled, a traditional D.C. school accepts 38 new students midyear, while the typical charter school accepts four. District schools that enroll students citywide, such as magnets and selective-entrance high schools, backfill at twice the rate of charter schools — still well below the rate of traditional neighborhood schools.

Authors Neil Campbell and Abby Quirk offered several suggestions for policies that can help to create more equitable backfill policies, starting with asking communities to collect data on student mobility and to make it — and by extension any disparities — public.

Here are three takeaways and three recommendations from their report, “Student Mobility, Backfill, and Charter Schools”:

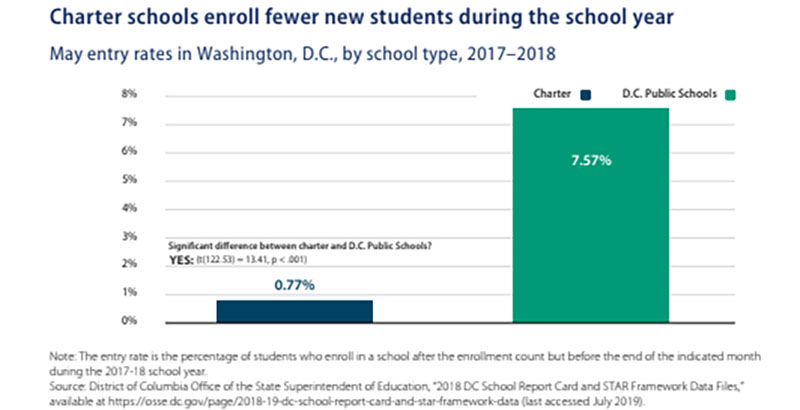

● Contrary to accusations that charter schools push out students who struggle or are disruptive, fewer students leave D.C. charter schools than district schools midyear. But the same charter schools, which serve 47 percent of the city’s public school students, accept far fewer children during the academic year. The midyear entry rate for district schools overall is 7.57 percent, versus 0.77 percent for charter schools.

Traditional district schools have to find seats for students who need a new placement no matter when during the year they move. But highly mobile students aren’t always guaranteed equitable access to magnets and other popular neighborhood schools. Citywide and selective-enrollment district schools have entry rates of 1.56 percent.

● Transfers’ impact on students can be dramatic, with one Baltimore study finding that students who change schools experience a drop of 5.62 points on reading tests and 2.62 points in math. Each additional move, other research has shown, increases the mean dropout rate by 8.4 percent. When these highly mobile students are concentrated in a particular subset of schools, the effect on them and their classmates is compounded.

● There are circumstances in which backfilling a seat is truly problematic, such as admitting a transfer student into older grades in a language-immersion school. But in most instances, they write, making it easier for new students to enroll in a high-performing school midyear would help interrupt a cycle that concentrates disadvantaged kids in the most challenged schools.

● One of only four states with clear backfill policies, Massachusetts requires charter schools to admit new students until Feb. 15 when there are vacant seats in at least the lower half of the school’s grade span. (The other states with explicit backfill requirements are Connecticut, Georgia and Idaho.) In other words, a Massachusetts K-5 charter school would need to admit a new first-grader midyear, but not a new fifth-grader. The state also considers a school’s willingness to backfill open seats when a charter school seeks to expand.

● With virtually all its schools constituted as charters operating within a unified enrollment system, New Orleans has an automated process for ensuring that students who leave one school midyear have a new seat. Schools are required to maintain the same number of seats in each grade served and to offer up any open seat for a new student.

● Charter school authorizers, policymakers and others should consider using a combination of data-gathering, transparency and financial incentives to push schools to broaden their backfilling practices. In D.C., for example, schools are funded primarily based on the number of students enrolled on “count day,” which takes place in October.

Because of this, schools are neither penalized for losing students as the year progresses nor incentivized to accept new ones. Adding a midyear count day would compensate schools for accepting more transfer students.

Likewise, maintaining — and publicizing — data on schools’ backfill policies and transfer rates would shed light on where highly mobile students end up and which schools should be pushed to make more room for them.

“Policymakers have an opportunity to meaningfully intervene here,” said Campbell, director of innovation for education policy at the think tank. “We think there’s a chance for policymakers to encourage, incentivize and/or require charter schools to do more in this regard.”

The report is part of an effort by CAP to re-examine its K-12 policy priorities in the run-up to the 2020 elections. The organization is seeking to bring a “balanced approach to discussions about charter schools,” Campbell added. “Charter schools are valuable, but there are also valid critiques.”

Disclosure: The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative provide funding for the Center for American Progress and The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)