Embracing the ‘Tough Conversation’: Teacher of the Year Finalists Speak Out On ‘Divisive’ History, Students’ Mental Health and Why Educators Are Not Superheroes

Teacher of the Year Finalists Reflect on ‘Divisive’ History, Mental Health

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

April 19 Update: The Council of Chief State School Officers named Kurt Russell the 2022 National Teacher of the Year.

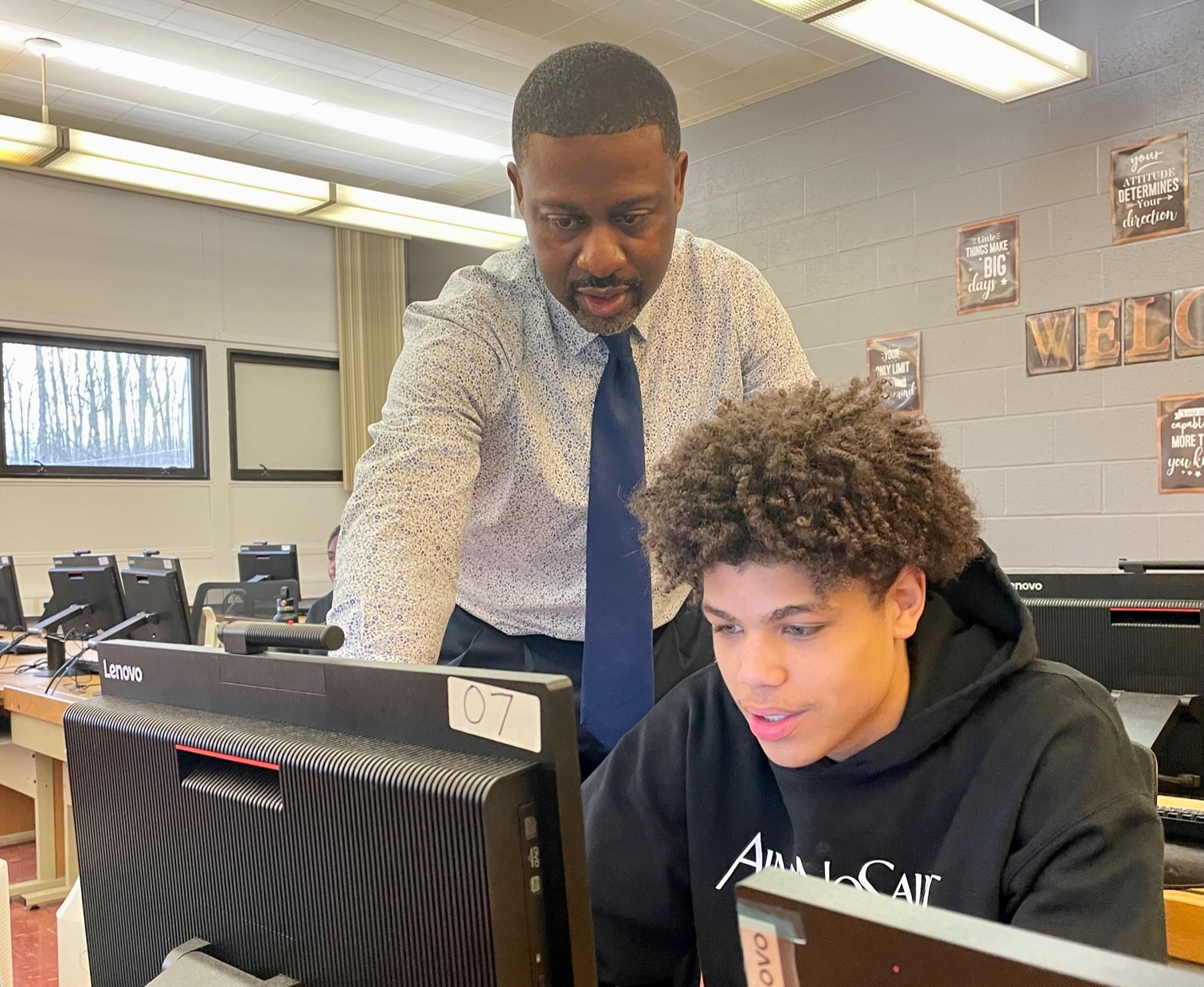

About 40 students at Oberlin Senior High School won’t be taking courses on Black history, race and gender oppression this fall — not because they’ve been canceled due to conservative opposition, but because Kurt Russell won’t be teaching them.

Jennifer Bracken, a counselor at the Cleveland-area school, said students would rather take those courses when Russell returns from his one-year sabbatical as Ohio’s Teacher of the Year. “They do not want to miss out on an opportunity to be in his class,” said Bracken. Russell is known for his energetic teaching style, and students told her that during remote learning, his class was the one “where being online was not bad.”

A “divisive concepts” bill currently advancing in Ohio’s state House could raise questions about Russell’s popular courses, but he said that just makes him want to teach with more “tenacity.”

“Students are really wanting to talk about these subjects. They want that tough conversation,” said Russell, one of four candidates to be 2022’s National Teacher of the Year. “It’s the adults who have a problem with it.”

Whether the topic is discrimination or the mental well-being of the nation’s students and teachers, this year’s finalists aren’t avoiding touchy subjects. Both Russell and Joseph Welch, the nominee from Pennsylvania, teach history. They tread daily in their classrooms through lessons being debated in statehouses and school board chambers across the country. Whitney Aragaki, the finalist from Hawaii, warns stressed-out students competing for spots in elite colleges that they’re putting their mental health at risk when they don’t take time to rest. And Autumn Rivera of Colorado said it’s time to drop the “toxic positivity” behind the notion that teachers are selfless and only in the profession “for the kids.”

The Council of Chief State School Officers will soon name one of the four this year’s national winner.

“I’m not a superhero,” said Rivera, a sixth grade science teacher at Glenwood Springs Middle School in a resort town west of Denver. “I’m a human being who has needs and has to take care of myself.”

While her district hasn’t experienced mid-year teachers resignations like some, she said many of her colleagues have “reevaluated” at least once this year whether they want to keep teaching. It will take more than Starbucks gift cards and fulfilling Amazon wish lists to retain teachers, she said, adding that significant salary increases, college loan forgiveness, and covering moving and housing expenses are more likely to reduce turnover.

As a teacher leader, Rivera advocates for educators’ perspectives in policy, but it’s the way she balances high academic expectations and tight relationships with students that earned her the state’s top honor, said Principal Joel Hathaway.

Her work with students to support a local land trust’s efforts to purchase a nearby lake and preserve the area as a state park is one example, he said.

“It’s the difference between having a science fair and having a science project that actually affects the quality of life in your community,” he said.

Like many middle school teachers this year, Rivera notices a “gap in maturity” among students due to limited opportunities to socialize in person during the pandemic. But a recent project in which students used digital tools to create presentations about elements on the periodic table reminded her what they’ve gained.

“This generation is going to be so resilient,” she said. “They could all have graduate degrees in tech after these two years.”

Aragaki, of Waiakea High School in Hilo, teaches both biology and AP environmental science. Her AP class is often just one of several college-level courses her students are taking. She sees them sometimes setting unrealistic — and unhealthy — expectations for themselves.

“I’m an alum of my own school. I tell them, ‘I sat in those desks where you are. I know what it’s like.’” she said. “We should push ourselves, but learning doesn’t always come through high-stress situations. We can learn in joyful and calm situations.”

She brings that sense of calm to the classroom through yoga, which she learned to teach last school year — “because I don’t have enough things to do,” she joked. Aragaki is also working on a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction and mentors teachers who are new to the school.

During the summer of 2020, she helped lead an enrichment class to prepare students for remote learning in the fall. This year, to ease them back into in-person communication, she required them to give 10-minute lessons to their classmates on a topic they knew well.

One taught Mandarin writing. Another demonstrated the proper way to throw a football. And a few Korean students showed classmates how to make the traditional cookies featured in the life-or-death Netflix series “Squid Game” — “but without the trauma response,” Aragaki joked.

Those presentations were a bridge to the next assignment — explaining an environmental science concept as if they were talking to an audience with no knowledge of the topic.

“If we can’t communicate science, we’re not helping society,” she said.

Sarah Polloi, the English department chair at Waiakea, said Aragaki has a talent for anticipating the needs and concerns not only of her students, but co-workers. When the school began to get a lot of new teachers, Aragaki and Polloi developed the New Warrior program, featuring sessions on issues unique to Waiakea and its challenges.

“She’s always the brain and I’m the muscle. She ropes me into these things,” Polloi said, adding that even veteran teachers participate in the weekly meetings. “It’s just a safe place to ask questions.”

Polloi has a parent’s perspective as well. Her daughter Maya, now an 11th grader, had Aragaki’s biology class last year. Aragaki held individual conferences with students throughout the year, helping Maya get through the year of remote learning.

“They would talk about curriculum, but also how my daughter was doing in general,” Polloi said. “She appreciated that one-on-one time.”

The finalists have left lasting impressions on their colleagues.

“I sort of thought I was with it. Then Joe came along,” said Larry Dorenkamp, who teaches U.S. history at North Hills Middle School with Welch. “Joe opened my eyes to the use of technology.”

During remote learning in the fall of 2020, the two traveled to historical landmarks and broadcast Zoom classes with a hotspot — a middle school twist on the way Pittsburgh’s own Fred Rogers introduced young children to his neighborhood.

Welch and Dorenkamp gave clues to their location and based on earlier lessons, students guessed where they were. One spot was where George Washington looked down over the forks of the Ohio River in 1753. Another was Fort Necessity, the site of an early battle in the French and Indian War.

For Veterans Day, the pair — who have become best friends outside of school — drove to Washington and featured war memorials on the National Mall. Even parents tuned into the lessons.

Welch was elected last year to the South Fayette Township School District, also near Pittsburgh, and said he hopes to bring teachers’ perspectives to policy decisions.

Welch, like Rivera, understands why this school year is pushing some educators to question their commitment to the profession. He counted 90 out of 135 school days this year that he’s given up a planning period or lunch break to cover another teacher’s class.

“Every teacher likes to be creative. You might take a walk and get new ideas,” he said. “That time does not exist.”

Many educators, he added, feel defensive about their work. He recently taught a lesson about Thomas Jefferson, and a student asked about Sally Hemings, a slave who had children with Jefferson. The next morning, he received an email from a parent, with the subject line: “Yesterday’s lesson.”

“I thought, ‘Here we go,’ ” Welch said, bracing himself for criticism. Instead the parent thanked him and said his lesson became a topic at the family dinner table.

Avoiding controversial material, Welch said, only leaves students unprepared to handle difficult issues in the future.

“Let’s learn from the past, but you don’t have to be defined by it,” he said. “We can love America without loving every aspect of its past.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)