Elementary School Kids Get Just 18 Minutes of Science a Day. That Has to Change

Teacher's view: Early science education helps students succeed in HS and college — and become the innovators of tomorrow.

Get stories like this delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

When students of all ages have the opportunity to engage in science in experiential, real-world ways, the better off they are. The high school students I teach take part in international science competitions, publish papers in prominent journals, and learn about and explore postsecondary opportunities in STEM.

Though I teach teenagers, I often meet elementary teachers through my work as an educator and board member of a pre-K-to-12 curricula organization. I love hearing how they spark joy in their budding young scientists and bring engaging, real-world experiences inside the classroom.

During one such conversation, I heard about second graders who learned about the properties of matter by studying how birds build nests. The kids created model nests, studied the effect of heating and cooling, and tested which materials offer protection from the rain. In another classroom, I heard about forces and motion investigations in which third graders compared activity on Earth versus space and applied aspects of the lesson to engineering a tool to secure objects in space.

It’s rich experiences like these that students need more of. Younger children who engage in in-class learning in tangible ways, conduct lab work to investigate scientific phenomena and run their own experiments are ultimately better prepared for high school classes like the ones I teach. This type of learning helps ignite passions in science and clarify difficult-to-understand concepts.

Student preparedness has been on my mind lately, because many kids need much more support than before the pandemic. Three years after COVID-19 disrupted education, students have knowledge gaps in biology, chemistry and physics that limit their ability to conduct fundamental and probing science experiments. Hands-on learning helps ignite passions in science and clarify difficult-to-understand concepts. If these shortcomings are not addressed, early learners will miss out on high-quality and engaging science instruction and older students will have difficulty accessing rigorous high school courses and STEM pathways in college and careers.

This is an issue everyone should care about. If schools are not helping to train the next generation of scientists, how will the country safely emerge from future public health threats and address climate change, while developing new technologies and inventions that improve all lives?

One of the first things education leaders and policymakers can do is devote more time to science in schools. Elementary teachers have reported spending just 18 minutes a day on science, compared with 89 minutes on reading and 57 on math. In addition, only 17% of K-3 teachers say they teach science all or most days every week. It is the responsibility of education leaders to understand why, and how this is shortchanging students. Bringing simple experiments into the classroom setting and designing training modules for age-specific groups can increase learning and comprehension of science even when teachers lack a strong background in the subject. Science should be integrated into all class subjects, including general reading and writing.

Another way teachers might engage students in science learning is by weaving real-world projects into curricula. Schools can run science fairs and invite members of the community, allowing students to deliver public presentations about their work. Local scientists can be invited for in-person visits, and those who are further away can discuss their work virtually. Meaningful field trips can also be engaging opportunities to bring what is happening in the classroom to life in novel ways.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many teachers learned to adapt to technology. Educators can build on that knowledge to incorporate stronger science practices and technologies in a post-COVID-19 pandemic classroom.

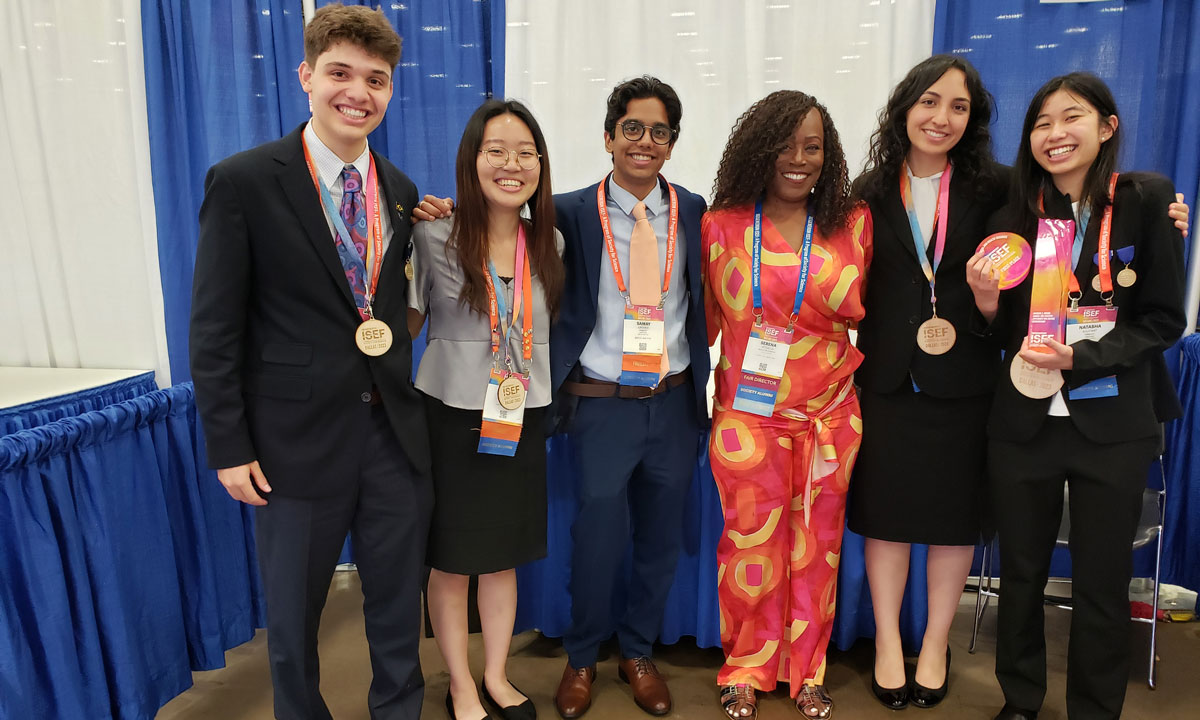

One strategy educators should consider trying is to help kids participate in science competitions. National Geographic featured my classes in the documentary “Science Fair,” which shows how to build enthusiasm for learning through science competitions. Well-run, respected contests, like the Regeneron Science Talent Search and International Science and Engineering Fair, can motivate students and enhance their learning. There are others for a range of ages, too. Preparing for and participating in a science competition enables students to practice key skills, tackle problems they care about and connect with STEM professionals.

Consider the example of one of my former students, who was skipping school and getting poor grades when he came to me as a sophomore. He liked my class and wanted to enter competitions. We had a heart-to-heart talk, and he agreed to start coming to school every day. Ultimately, he devoted himself to a research project on improvements to window glass that reflects and refracts light to better regulate the temperature of houses, depending on the season. He didn’t take the top prize, but he re-engaged in school and went on to graduate from a top university and become a successful entrepreneur.

Other students I’ve had the privilege of teaching have been featured in prominent journals, gone on to medical school or Ph.D. programs and are shaping the sciences and industry. All kids deserve these types of opportunities, and all students should be trained to think and apply what they know toward addressing global problems.

I wish this kind of teaching and learning were the norm. It is possible, but it will take a collective understanding that every child needs high-quality, rigorous science education from an early age, and that schools need to devote more time and attention to this critical subject. If education leaders, policymakers, and teachers commit to those principles, I have no doubt students will soar — resulting in bright futures and a better world for all.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)