Educators & Experts Say Personalized Learning Is Not About Technology or Money but Leadership and Relationships

A version of this column first appeared on the Education Writers Association blog.

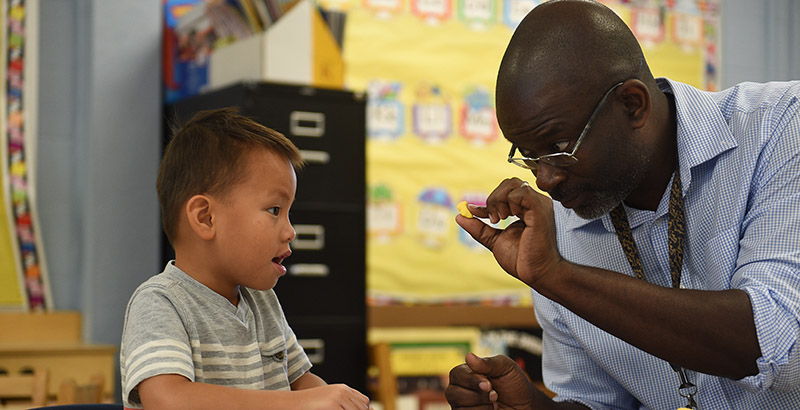

The media images illustrating students in “personalized learning” environments often look something like this: elementary schoolers with headphones on, looking at tablets, or teenagers typing away on laptops.

But during a recent panel discussion, experts and educators sought to make one thing clear: Personalized learning is not about technology, and you don’t need a lot of money to carry it out.

“It’s really about leadership,” said Heidi Vazquez, a third- and fourth-grade teacher at The Compass School in Kingston, Rhode Island, at the Education Writers Association’s national seminar in Los Angeles.

“It’s definitely a lot easier [with money], and technology is an amazing tool to help you get there,” Vazquez said, “but … in order to do this work, the thing that teachers need the most … is time.”

“They need time to collaborate; they need time to figure it out,” Vazquez said. “The pacing question is the biggest piece of it.”

Also on the panel were April Chou, vice president of education at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and Larry Cuban, a professor emeritus of education at Stanford University and skeptic of technology-based school reform.

‘The Difficulty of Innovating’

The panel comes at a time of keen interest — and investments — in personalized learning. In June, the Center on Reinventing Public Education published a report identifying several key challenges of work in six school systems trying to create personalized learning models in collaboration with regional partners. The effort was funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, as was the study by the Center on Reinventing Public Education looking at how well it worked.

“Taken together, the experiences of the schools … followed a familiar pattern of promising practices struggling to replicate at scale across systems,” the report says, and they “underscore the difficulty of innovating inside a system that was never designed for innovation.”

For instance, teachers and principals had difficulty translating abstract goals into “meaningful student outcomes” to guide classroom practices, and central offices “failed to fundamentally change structures, policies, and supports to facilitate innovation,” the report said.

Even at CZI, an organization formed by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and his wife, Dr. Priscilla Chan, that seeks “to advance human potential and promote equal opportunity,” officials are cautious about technology’s role in personalized learning.

“It’s really critical to recognize it, that we see technology as a tool, and it’s only just that — a tool in the hands of people that can be powerful depending on how we use it,” Chou said. “Technology has a role to play, but at the center of any of these teaching and learning interactions is really the relationship between a student and a teacher. I think we miss the mark collectively when we think about personalized learning as being synonymous with technology.”

Chan and Zuckerberg are expected to invest “hundreds of millions of dollars a year” in “whole-child personalized learning” through CZI, as Education Week explained in a recent story.

As more institutions seek to expand personalized learning initiatives — including the U.S. Department of Education, which doled out $350 million in grants under the Obama administration — advocates and experts struggle to agree on a precise definition for personalized learning.

A Historical Perspective

The nascence of personalized learning, in fact, can be seen in little-known initiatives of the 1920s and 1930s like the Gary Plan, the Dalton Plan, and the Winnetka Plan — all evidence of personalized learning as defined by “an earlier generation of reformers who loved innovation,” Cuban said.

But the personalized learning movement of the 21st century is facing layers of conflict: chief among them the coexistence of the “age-graded school system” (in which students are separated into different classrooms based on age) and standards-based accountability, Cuban said.

Cuban said the age-graded school remains the “dominant” structure in U.S. education, even in places that seek to innovate in a variety of ways to differentiate instruction and better address individual needs.

During the EWA panel, Cuban also discussed the standards-based accountability system that we now know so well — a system that requires students to demonstrate mastery of a certain set of knowledge and skills by a certain time, largely measured by periodic tests. This accountability system that now governs public schools across the country inherently conflicts with the personalized learning initiatives that districts and advocates are so arduously trying to get off the ground, Cuban said.

“Many schools trumpet their alignment of lessons to Common Core standards and personalized learning in the same breath,” Cuban said. “They have learned that those tensions exist, but in my own research in 2016, 2017, they seldom arose in any discussion with teachers, principals, and superintendents who were enamored with personalized learning.”

Developing metrics for how to measure personalized learning is a work in progress, Cuban said. Tying outcomes back to how students perform on traditional assessments, or even to student engagement, inevitably perpetuates the tension between allowing students to progress at their own pace and the edicts of standards-based accountability. And early studies of how well personalized learning systems are serving students have yielded mixed results.

What questions should parents, educators, and other interested parties be asking as they seek to understand personalized learning and how it works in the classroom?

Start with the “why?” and “how?”:

● Ask school or district leaders:

ဝ What are the purposes of the program that you now are going to invest in?

ဝ How would you define success?

ဝ What does personalized learning mean to you?

ဝ What is your vision for personalized learning?

ဝ What culture shifts are you seeing (or not) as a result of personalized learning?

● Ask teachers:

ဝ What are the purposes of personalized learning to you as a teacher?

ဝ How would you define success in your classroom?

ဝ What culture shifts are you seeing (or not) as a result of personalized learning?

● Ask students:

ဝ How does this classroom approach differ from prior experiences in school?

ဝ Show me a project you’re working on and what you’ve learned from it.

ဝ How does your teacher help you?

Disclosure: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provides financial support to The 74.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

;)